eBook - ePub

Masons, Tricksters and Cartographers

Comparative Studies in the Sociology of Scientific and Indigenous Knowledge

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Masons, Tricksters and Cartographers

Comparative Studies in the Sociology of Scientific and Indigenous Knowledge

About this book

In an eclectic and highly original study, Turnbull brings together traditions as diverse as cathedral building, Micronesian navigation, cartography and turbulence research. He argues that all our differing ways of producing knowledge - including science - are messy, spatial and local. Every culture has its own ways of assembling local knowledge, thereby creating space thrugh the linking of people, practices and places. The spaces we inhabit and assemblages we work with are not as homogenous and coherent as our modernist perspectives have led us to believe - rather they are complex and heterogeneous motleys.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Masons, Tricksters and Cartographers by David Turnbull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘ON WITH THE MOTLEY’: THE CONTINGENT ASSEMBLAGE OF KNOWLEDGE SPACES

To us, science, art, ideology, law, religion, technology, mathematics, even nowadays ethics and epistemology, seem genuine enough genres of cultural expression to lead us to ask (and ask and ask) to what degree other peoples possess them and to the degree they do possess them, what form do they take, and given the form they take, what light has that to shed on our own versions of them.1

Comparing Knowledge Traditions

This chapter develops the argument that an explicit focus on the localness of knowledge production provides the possibility of a fully-fledged comparison between the ways in which understandings of the natural world have been produced by different cultures and at different times. Cross-cultural comparisons of knowledge traditions have hitherto been largely absent from SSK.2 A necessary condition for fully equitable comparison is that Western contemporary technosciences, rather than being taken as definitional of knowledge, rationality or objectivity, should be treated as varieties of such knowledge systems. Though knowledge systems may differ in their epistemologies, methodologies, logics, cognitive structures or in their socio-economic contexts, a characteristic that they all share is their localness. However, knowledge is not simply local, it is located. It is both situated and situating. It has place and creates a space. An assemblage is made up of linked sites, people and activities; in a very important and profound sense, the creation of an assemblage is the creation of a knowledge space. The motley of scientific practice, its situated messiness, is given a spatial coherence through the social labour of creating equivalences and connections. Such knowledge spaces acquire their taken for granted air and seemingly unchallengeable naturalness through the suppression and denial of work involved in their construction. However, since they are motleys, they are polysemous and are capable of many possible modes of assemblage and of providing alternative interpretations and meanings. Hence all knowledge spaces are potential sites of resistance, as will be seen in the Chapter 3.

Knowledge spaces have a wide diversity of components: people, skills, local knowledge and equipment that are linked by social strategies and technical devices or ‘heterogeneous engineering’.3 From this spatialised perspective, universality, objectivity, rationality, efficacy and accumulation cease to be unique and special characteristics of technoscientific knowledge, rather these traits are effects of collective work of the knowledge producers in a given knowledge space. To move knowledge from the local site and moment of its production and application to other places and times, knowledge producers deploy a variety of social strategies and technical devices for creating the equivalences and connections between otherwise heterogeneous and isolated knowledges.4 The standardisation and homogenisation required for knowledge to be accumulated and rendered truthlike is achieved through social methods of organising the production, transmission and utilisation of knowledge. As Steven Shapin has argued, the basis of knowledge is not empirical verification, but trust: ‘Trust is, quite literally, the great civility. Mundane reason is the space across which trust plays. It provides a set of presuppositions about self, others, and the world which embed trust and which permit both consensus and civil dissensus to occur.’5 In addition to social strategies, the linking of the heterogeneous components of a knowledge tradition is achieved with technical devices which may include maps, templates, diagrams and drawings but which are typically techniques for spatial visualisation.

The work of Latour, Collins, Shapin, Star, Hacking, and Rouse among others has shown that the kind of knowledge system we call Western science depends on a variety of social, technical and literary devices and strategies—assemblages which move and engage local knowledge. I suggest that it is having the capacity for movement that enables local knowledge to constitute part of a knowledge system. This mobility requires devices and strategies that enable connectivity and equivalence, that is the linking of disparate or new knowledge and the rendering of knowledge and context sufficiently similar as to make the knowledge applicable.6 Connectivity and equivalence are prerequisites of a knowledge system but are not characteristics of knowledge itself. They are produced by collective work and facilitated by technical devices and social strategies. Differing devices and strategies produce differing assemblages and are the source of the differences in power between knowledge systems. In order to give some flesh to the local/spatial thesis and to provide specific examples of differing social, moral and technical components in a range of cultural and historical contexts, I want to turn immediately to a brief consideration a variety of Anasazi, Inca, and Australian Aboriginal knowledge spaces. In later chapters I consider in more detail the assemblage work of the Gothic Cathedral builders (Chapter 2) and the Pacific navigators (Chapter 4).

The Anasazi

The Anasazi were a group of North American Indians who established themselves in what is now the Four Corners region (Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona) of the United States from around 200–700 A.D. They not only managed to survive in this most inhospitable region where the temperature ranges from −20° F to 100°F, and where there is only 9” of rain often in destructive summer bursts, but they also created a complex society.7 This society came to an abrupt end in about 1150 A.D. (possibly due to the drought between 1130 and 1180, though this is debatable). At its peak it consisted of 75 communities spread across 25,000 square miles of the San Juan Basin linked into a socioeconomic and ritual network centred on Chaco Canyon.8

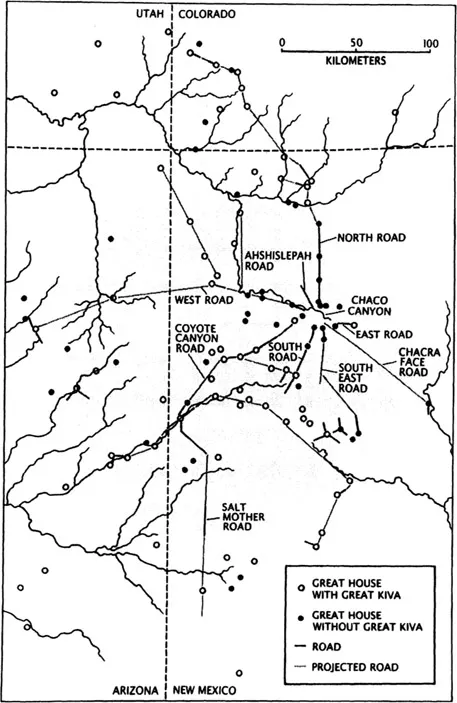

On the floor of Chaco Canyon massive stone buildings were built up to four stories high with hundreds of rooms including vast storage areas and huge round underground Kivas or temples (see Fig. 1). Chaco was connected to many of the outlying communities by over 400 km of roads. In addition to the great buildings and the roads, the Anasazi built an enormous irrigation system with check dams, reservoirs, canals up to 50′ wide, irrigation ditches, and levelled fields with banks.9

The labour and materials involved were immense. It is estimated, for example, that upwards of 200,000 Piñon Pine beams up to 60′ long had to be carried into the canyon from distances of thirty miles or more. The purpose of this staggering effort, in a society that had no wheeled vehicles, seems not to have been the accommodation of large numbers of people. The archaeological record reveals a number of anomalies suggestive of a low population at each site. Despite the large number of rooms in each of these massive complexes, relatively few rooms were designed solely for habitation. One of the great buildings, Pueblo Bonito for example, may have only housed a hundred or so

Figure 1 Kivas and roads of the Chacoan Region. Figure by Tom Prentiss. With kind permission of Nelson H.Prentiss.

people. Correspondingly very few burial sites have been found. However at Pueblo Alto, on the northern rim of the canyon where the Great North road begins, there are large piles of broken pots, far more than even the most careless of populations could have accumulated. In addition, archaeologists have found large amounts of trade items imported from great distances: turquoise from 160 miles to the SE, shell from Pacific coast, copper bells and macaw feathers from Mexico, and chipped stone and pottery from Chuska 80 miles away. The road system also poses something of a mystery. The ‘roads’ are unusually straight and wide and without an obvious utilitarian function. All these factors suggest that ‘Chaco Canyon from an archaeological perspective functioned primarily as a ceremonial centre gathering people together for the exchange of information and material goods’.10

It appears that the key to supporting a population estimated at up to 10,000 in such a marginal environment was the development of an agricultural and storage system which enabled them to grow and redistribute a surplus. But by itself that would not have been enough. To successfully transform an almost totally arid environment, to coordinate the work of large numbers of people over a vast area and to ensure the growth, storage and redistribution of food, a large amount of knowledge and information had to be developed, sustained and transmitted. This was achieved primarily with the calendar, along with ritual, myth, poetry and architecture. Clearly, however, the role of knowledge in Anasazi society, as in any other, does not have a merely functionalist role. It also reflects the desire to render the world intelligible and to celebrate existence. Why else would a culture of such complexity and sophistication develop in such an environment? Indeed one could speculate that it is the human propensity for cultural elaboration and the growth of knowledge that provides the conditions for the possibility of social development in all manner of environments. Zuidema argues that:

Anthropologically speaking we should not look at these systems from the point of view of the prehistory of Western science and astronomy but from the standpoint of theoretically analysing the human propensity to classify the social and physical universe. Kinship and astronomy (in their broadest sense) complement each other, and provide equal opportunities, in a non-evolutionary way, of studying human variation in using limited sets of variables for the general purpose of classification.11

The central importance of the Anasazi knowledge system to their culture, and the power of its techniques for preservation and transmission, are revealed in the fact that it has survived largely intact from prehistoric times. It is still an active system in the Pueblo astronomy of the Hopi and Zuni Indians despite pressure from Spanish and Anglo cultures and despite the disappearance of the Anasazi.12

Whoever keeps the calendar, be it the town chief, ta’wa mongwi or pekwin (the sun priest), is responsible for structuring pueblo life on both a day-to-day and a yearly basis. Almost all pueblo activities, and certainly all those that are critical to village survival, both mundane and sacred, are predicted, scheduled, and executed according to the calendar, e.g., seed preparation, ditch maintenance, planting, harvesting, hunting etc., and the accompanying ceremonies.13

Hopi astronomical, cosmological and religious knowledge is structured by orientation. The basic axis is based on the intersection of the lines joining midsummer and midwinter rising and setting points of the sun, and is hence solstitial as opposed to our cardinal directions; in addition they place great value on up and down.14 For the Hopi, the solstitial directions ‘provide a general cosmological framework which draws apparently unrelated natural phenomena into an organic unity’.15 This directional framework is manifested in their ‘verbal art’ or ritual poetry, religion, and astronomy and has its most overt expression in the calendar.16

The calendar is maintained by the sun priest’s observation of the sun’s seasonal passage past markers on the horizon and through the passage of light and shadow in buildings and rock arrangements like that on top of Fajada Butte (see Fig. 2). At the solstice the sun’s rising point remains stationary on the horizon for several days making the actual solstice difficult to determine. The priest resolves this difficulty by anticipatory observation for two weeks before the solstice, which allows preparation for ceremonies.17 It is crucial that the solstice be accurately forecast because the timing of the planting calendar is of great moment in an environment with a short growing season, and where the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction From rationality to messiness: Rethinking technoscientific knowledge

- Chapter 1 ‘On with the motley’: The contingent assemblage of knowledge spaces

- Chapter 2 Talk, templates and tradition: How the masons built Chartres Cathedral without plans

- Chapter 3 Tricksters and cartographers: Maps, science and the state in the making of a modern scientific knowledge space

- Chapter 4 Pacific navigation: An alternative scientific tradition

- Chapter 5 Making malaria curable: Extending a knowledge space to create a vaccine

- Chapter 6 Messiness and order in turbulence research

- Conclusion Rationality, relativism and the politics of knowledge

- Bibliography

- Index