- 212 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Relational Grammar

About this book

Relational Grammar had its beginnings in the early 1970s. In this theory of the structure of language grammatical relations are taken to be `undefined primitives'. The set of relations recognised includes subject, direct object, indirect object and a number of `oblique' relations including benefactive, locative and instrumental. This is the first book that describes the theory's basic ideas, evaluates them and compares them with other approaches in other theories. The treatment is straightforward, and should be comprehensible to anyone conversant with traditional grammatical terminology. All unfamiliar terms and conventions are explained and illustrated. The book is written for students of modern theories of grammar, but it should also be of relevance and interest to descriptive and comparative linguistics. It contains a wealth of data on morphology and syntax and also includes comparisons of Relational Grammar analyses with those of 'non-aligned' linguistics who are working with much the same data.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Outline

1.1

Basic notions

Relational Grammar (RG) was developed primarily by David Perlmutter and Paul Postal in the early 1970s. In this theory grammatical relations are taken to be undefined primitives. The set of relations recognized includes subject, direct object, indirect object, and an as yet undetermined number of oblique relations including benefactive, locative, and instrumental. The three relations subject, object, and indirect object are collectively called terms. These and the obliques form a hierarchy as in [1]:

| [1] | subject | direct object | indirect object | obliques |

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

The terms are conventionally referred to by their position in the hierarchy, so a subject is referred to as 1, a direct object as 2, and an indirect object as 3. 1 and 2 are known collectively as nuclear relations and 2 and 3 as object relations.

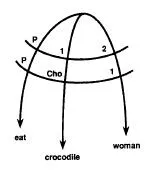

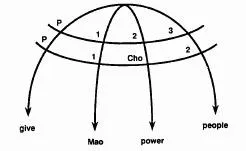

The relational structure of a clause can be represented in a stratal diagram. The relational structure of the active sentence [2a] is displayed in [3a] and the relational structure of its passive counterpart [2b] is shown in [3b]:

[2a] The crocodile ate the woman.

[2b] The woman was eaten by the crocodile.

[3a]

[3b]

In these networks linear order has been abstracted and the substructure of the predicate and of the noun phrases has been ignored. The active clause [2a] is considered to have a predicate, designated P, a subject, designated 1, and a direct object, designated 2. There is only one stratum or level. In the relational structure of the passive there are two strata. The initial stratum is the same as the sole stratum of the active, but the second and final stratum reflects revaluations. The initial direct object has advanced to subject and the initial subject has been demoted to the chômeur relation (abbreviated Cho). The notion of chômeur is peculiar to Relational Grammar and represents one of the innovations of the theory. Informally the chômeur relation is the relation held by a nominal that has been ousted from term status, i.e. from 1, 2, or 3. A chômeur lacks at least some of the grammatical properties of the corresponding term; the subject chômeur in [3b], unlike the subject in [3a], fails to control agreement on the verb, for instance, and occupies a peripheral, optional position in the clause. The term chômeur comes from the French word for unemployed or idle person. The related term chômage is also used. Thus one could describe the crocodile in [2b] being ‘put en chômage’ or ‘going into chômage’.

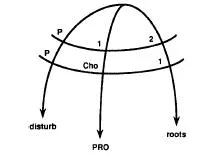

An agentless passive such as Their roots had been disturbed is allotted an initial stratum in which the initial 1 is unspecified and consequently has no realization. This generic nominal is usually represented in recent Relational Grammar literature as PRO:

[4a] Their roots had been disturbed.

[4b]

In early versions of the theory initial stratum relations were held to be linked to semantic roles in a universal way, an agent always being an initial 1, a patient an initial 2, and the recipient of a predicate like give an initial 3. This principle is known as the Universal Alignment Hypothesis (Perlmutter and Postal 1984a: 97; orig. 1978). This hypothesis is untenable in its strict form (see section 2.2.), but with a two-place verb a prototypical agent and a prototypical patient, as in The man hit the dog, are always taken to be initial 1 and 2 respectively.

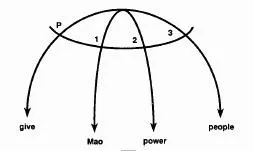

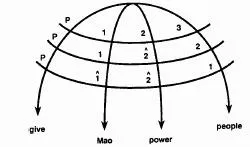

The label indirect object is used for the recipient in a clause like [5a] but not for the first object in the two-object construction exemplified in [5b]. A sentence like [5a] is considered to have a single stratum with initial relations being reflected directly (as shown in [6a]), but a sentence like [5b] is considered to involve two strata with the initial indirect object having advanced to direct object in the second stratum pushing the initial direct object into chômage [6b]:

[5a] Mao gave power to the people.1

[5b] Mao gave the people power.

[6a]

[6b]

This analysis conflicts with a common traditional analysis in which the first object of the two-object construction is called the indirect object and the second the direct object. There are facts that support the Relational Grammar analysis. The most obvious one is that the notional indirect object, typically a recipient, occupies the position immediately after the verb. The other is that the first object but not the second can be the subject of the corresponding passive, as in [7a]:

[7a] The people were given power by Mao.

[7b]

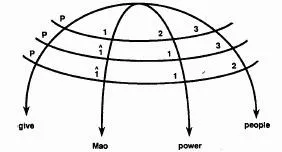

It might appear that in some varieties of English the second object can also correspond with the subject to the passive since there are sentences of the pattern Power was given the people by Mao. However, these are derivable from the basic pattern as in [5a] with the advancement of 2 to 1 and subsequent advancement of 3 to 2:

[8a] Power was given the people by Mao.

[8b]

But it should be noted that this analysis is not generally agreed on. The point is taken up in section 2.7.2.

Note that in [7b] and [8b] chômeurs are indicated by the use of a circumflex (from the word chômeur!) over the sign for the term relation held in the immediate preceding stratum. This is an alternative to the abbreviation Cho and is useful, as here, where there is more than one chômeur. Since, however, chômeurs arise only from the demotion of terms and cannot be revalued, the distinction between a 1-a 2-, and a 3-chômeur is always apparent from the last stratum in which a term relation was held.

Where there is an indirect object construction, as in [5a], but no double object construction (see [5b]), the indirect object cannot become the subject of the passive. This is to be expected on the assumption that the passive of a transitive clause in English involves the advancing to subject of a direct object only. Thus the following have no passive with the recipient as subject:

[9a] All the workers contributed funds to the party.

[9b] Some donated money to the church.

The 3 to 2 interpretation holds for those double object constructions that have no indirect object counterpart such as the following:

[10a] No one envies you the task.

[10b] God will forgive you your sins.

[10c] They could have spared him the trouble.

[10d] Liz allowed Richard a second chance.

[10e] Waterhouse bet Golea ten grand.

[10f] They refused his wife permission to visit him.

[10g] No one begrudged the little Aussie battler his success.

It also applies to various idiomatic expressions such as to give someone’s back a rub or to give something or someone the once over. It holds too in those languages such as Manam, Blackfoot, Mohawk, Tzotzil, and Huichol where there is never any indirect object alternative to the double object construction. All these constructions are interpreted as involving obligatory 3 to 2 advancement (see also section 8.2).

In English a beneficiary can be advanced to 2 where it is the potential recipient of the patient (initial 2) as in [11] but not where it is just the beneficiary of the action as in [12]:...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations and Symbols

- Chapter 1: Outline

- Chapter 2: Some Clause-Internal Revaluations

- Chapter 3: Reflexives and Impersonals

- Chapter 4: Multinode Networks

- Chapter 5: Clause Union

- Chapter 6: Relations and Strata

- Chapter 7: Describing Different Nuclear Types

- Chapter 8: Overview

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Relational Grammar by Barry Blake in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.