- 98 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Word Meaning

About this book

In Word Meaning, Richard Hudson introduces readers to the techniques of lexical semantic analysis.

Word Meaning:

* is based on a problem-solving approach to language

* introduces readers to the technical terminology and basic principles associated with the analysis of word meaning

* shows students how to apply these terms and principles to English

* includes suggestions for further work

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

WORDS AND MEANINGS

1

We distinguish between a word and its meaning. Both the word and its meaning are concepts, about which we know various facts. Words that share the same meaning (though not necessarily the same style) are synonyms.

We start with a very ordinary word indeed, bicycle. What does the word bicycle mean?

Before we answer this question, let me remind you that we are talking about what you have in your mind. One thing you certainly know is the word bicycle: you know how to pronounce it, maybe you even know how to spell it, and you certainly know that it is a noun (though you may not be aware that you know any of these things). You must know all these things, otherwise you couldn’t use the word as you (no doubt) do use it. Another way of saying all this is to say that bicycle is a CONCEPT in your mind, and that you know a variety of FACTS about it—the fact that it is spelt ‘bicycle’, that it is pronounced with stress on the first syllable, that it is a noun, and so on. We don’t need to agonise over exactly what a concept is; for our purposes it is enough to be clear that it is a part of our knowledge about which we know facts.

Concept

Facts

The whole of this course is about concepts and the relations between them, so we need to be able to talk easily about the individual concepts. The book that you are reading now has a concept in your mind, and we could call it simply ‘this book’, but it’s harder to know what to call the concepts for individual words like the word bicycle. An easy answer is simply to call it ‘the word bicycle’. which works well because it distinguishes the word from every other concept in your mind. Even more easily, you can miss out ‘the word’ and leave just the underlined word itself, bicycle. Underlining (or italics) is a standard convention that you will find in all linguistics books for picking out words that are ‘quoted’ rather than used in their ordinary way. I shall apply this principle consistently, and I recommend you to do the same for reasons that I shall explain below. We shall see later that this system for naming words isn’t quite precise enough, but it will do to start with. The name of your concept for the word bicycle, then, is just bicycle.

One other fact that you know about bicycle is that it means…. Well, what does it mean? Whatever it is must also be part of your knowledge, because that’s what we mean by saying that you know the meaning of bicycle: therefore it must be another concept. What shall we call this concept? How about bicycle. for example? No, that would be hopelessly confusing, because we are already using bicycle as the name for a concept that is a noun, has three syllables and so on. What bicycle means has nothing to do with syllables, but has a lot to do with wheels, transport and so on. It is absolutely essential to keep the two concepts distinct, so we shall call it ‘bicycle’—no underlining, but single quotes. In fact, when we use the word as a name for its meaning we are actually using it in the normal way. That’s what words are: names for their meanings. So the answer to our question is that bicycle means ‘bicycle’.

If this distinction between the word and its meaning strikes you as blindingly obvious, you are lucky. Many people find it extremely difficult to think of words as separate from their meanings, so even at the end of this course I find that some students are still capable of writing things like: ‘Wine is a noun and is something you drink.’ This is nonsense: what you drink isn’t a noun, but a liquid. What they really mean is: ‘Wine is a noun, and wine is something you drink.’ (Just after writing these words I read an essay by a bright third-year undergraduate which contained the following sentence: ‘Like virtually all the creatures in the “pets” category, the ox is a monosyllable’!)

Indeed, one characteristic of ‘primitive’ thinking is the confusion of words and their meanings. Most societies have words that are ‘taboo’ because the concepts that they mean are ‘taboo’. We don’t have to go to exotic tribal societies to find examples; just think of any ‘fourletter’ word. Why is it bad? Is it because its meaning is in some sense forbidden? Why should that carry over to the word itself? The point is that we all grow up in a society where the difference between words and their meanings tends to be blurred (as witness the game ‘I-spy’, where you claim to be able to see ‘something beginning with B’?), so we have to fight against this tendency.

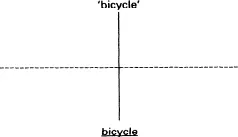

We are already recognising the distinction by underlining words but not their meanings, but we can make it even more clearly by using diagrams. In all the diagrams in this course, words are written below their meanings. (Think of words as relatively concrete and down-to-earth, with meanings as relatively abstract and existing on a ‘higher’ plane.) Just in case the word-meaning distinction doesn’t leap out at you from the vertical dimension plus the unde rlining of the word, a dotted horizontal line will separate them. Here, then, is our first diagram, showing the relation between the word bicycle and its meaning, ‘bicycle’:

(1)

Having distinguished words and their meanings, we can now put the distinction to work in our first exercise in the analysis of meaning. Perhaps the simplest kind of analysis is to identify SYNONYMS—words that have the same meaning. Does English contain any synonyms for bicycle? Yes, we have at least one: cycle. It is easy to test for synonymy:

Synonym

Test for synonymy

If two words W1 and W2 are synonymous, then anything which can be described using W1 (in the relevant meaning) can also be described using W2, and vice versa.

Is it possible to imagine something which could be described as a bicycle but not as a cycle? Presumably not. But what about a cycle which isn’t a bicycle? It’s true that the cycle of the seasons isn’t a bicycle; but that’s not relevant, because it involves a different meaning of cycle. For the present we must just bear in mind that many words have more than one meaning, so in testing for synonymy we have to ignore all the irrelevant meanings.

Please notice that our definition of ‘synonym’ is quite a lax one, and does not require pairs of synonyms to share all their meanings; one shared meaning is enough. Nor does it require them to be interchangeable even in the relevant meaning. This is important because words that share the same meaning very often (in fact, normally) are different in STYLE. For instance, you may well feel that there are situations where cycle would sound odd (a bit archaic, perhaps?), but where bicycle would be fine. This is not because their meanings are different but because the situations in which you use the words are different.

Style

Synonyms make the differences between words and their meanings somewhat more interesting than in the ‘bicycle means “bicycle” ’ example. The point is that at least one of the words must have a meaning whose name is not that word itself. Take our examples, bicycle and cycle. If they have the same meaning, there must be just one concept which doubles up as the meaning for both words, so it has just one name. If we call it ‘bicycle’, then we must say that the meaning of cycle is ‘bicycle’ (not ‘cycle’); and if we call it ‘cycle’, then bicycle means ‘cycle’.

Which name should we choose in such cases? It really doesn’t matter, so long as we are consistent—i.e. so long as we never use any other name for that concept. This is such an important point that I shall promote it to the status of a principle:

The Labelling Principle

We can use any names we wish as labels for concepts, so long as we use them consistently. The only other criterion is convenience.

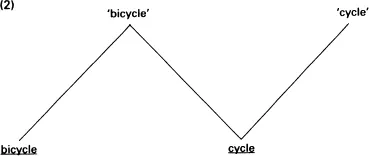

I shall choose ‘bicycle’, because we already know that cycle has (at least) two meanings, so it will be convenient to release ‘cycle’ for one of them. Here then is another diagram, this time showing the synonymy of bicycle and cycle. and also the fact that cycle has two meanings:

(2)

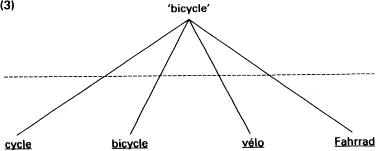

A curious consequence of the Labelling Principle is that the word and the label for its meaning need not even belong to the same language. If we wanted to use the French word vélo as the basis for our name, we could call the meaning of bicycle and cycle ‘vélo’. But this means that vélo qualifies, by our definition, as another synonym of bicycle. In other words, when a word in one language translates a word in another language, this is because they share the same meaning and are synonyms. For good measure we can add the German word Fahrrad to our list, and show the relations in the diagram below.

On this first leg of our journey through your mind we have looked in detail at a tiny area, where you keep your concepts for ‘bicycle’ and the word bicycle. This has given us a chance to make two distinctions

(3)

which will be vital in the remainder of this course: between a word and its meaning, and between meaning and style. These distinctions allow us to say that bicycle and cycle have the same meaning, ‘bicycle’, even if they differ in style; and we can even say that vélo means ‘bicycle’, without falling into the trap of saying that it means bicycle!

You may be surprised to notice that in talking about the me...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- IN THE SAME SERIES

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- A ROUTE-MAP

- 1: WORDS AND MEANINGS

- 2: SENSES AND REFERENTS

- 3: CLASSIFICATION

- 4: TYPICALITY

- 5: DEFINITIONS

- 6: ENCYCLOPEDIAS

- 7: LEXEMES

- 8: CONSISTENCY

- 9: ARGUMENTS

- REVISION OF TERMINOLOGY AND CONCEPTS

- 10: CHANGE

- 11: HUMANITY

- 12: PARENTS

- 13: FAMILIES

- 14: VERBS

- TAKING IT FURTHER

- REFERENCES

- APPENDIX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Word Meaning by Richard Hudson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.