![]()

Chapter 1

Young children and movement

If you can’t run fast enough, you don’t get to play. It’s not fair, it’s really not fair!

Scott, aged 5

By the time they are five – or six or seven – most children have made tremendous strides in their motor development. They can run and jump and climb and swing and many like to challenge themselves further by adding bicycles or roller blades, even skis! Others love to dance and can learn complex step patterns. These activities require quite a sophisticated sense of balance, coordination and control but they give a great sense of enjoyment and satisfaction. Acquiring these skills also allows the children to join in group activities and so they learn the social skills of playing together, e.g. turn taking and sharing and following someone else’s lead. They learn to follow the ‘rules’ in a game and so begin to empathise with children who win and those that lose. All of this is part of the rough and tumble of growing up.

But some do not develop the movement skills that allow these things to happen. For them, coping with everyday activities is challenging enough, even overwhelmingly difficult. And these can be bright children with no apparent neurological disorder. So what is wrong? Why should some children be limited in this way? Why can they not do the things other children enjoy? And what will be the effect on their confidence and self-esteem? Bundy (2002) shows that children with motor problems may well join in activities but with less enjoyment. Sadly their incompetencies are obvious to the other children with negative effects on their self-esteem.

These children must be helped at a very early age for all of these reasons, but primarily because children learning motor skills ‘out-of-step’ with their chronological age may find it much harder when they self-evaluate their progress against that of their friends. Furthermore, it is widely accepted that the development of controlled movement has a significant influence on the development of thinking and understanding. There is a mind/body link (Winston 2004). Movement helps to map the brain (Goddard Blythe 2008) so children need to experience movement in order to foster their development, to learn about themselves, how they interact with their environment and the constant adaptations they must make as it changes.

So the ability to move well is important in its own right and because it permeates into other facets of the children’s development, e.g. learning about themselves and how to cope in a changing, more demanding world.

Unfortunately movement difficulties can be complex and long lasting, even with regular support. Children can have different blends of long lasting difficulties and different levels of disability and this can make accurate diagnosis quite tricky. There is not one typical dyspraxic child. Moreover, the characteristics of dyspraxia can overlap with other learning differences such as poor attention, literacy and dysgraphia (Reid 2005) However, activities to help can be fun as well as being effective, and this should be the aim of any intervention programme. Children without difficulties can join in too. No one need feel different. In this way all the children can look forward to movement lessons, especially if difficulties are dealt with in a calm, ‘let’s all practise’ kind of way and the children are helped to reflect on the progress they have made.

An important benefit of early intervention is that very young children tend to be engrossed in their own activities and so are less likely to compare their own performance negatively with others more skilled in this motor field. Hopefully, with appropriate and timely support, their difficulties can be alleviated before others become aware of them and before they themselves become distressed and reluctant to try. No label is indelible but close observation to identify specific difficulties and regular, preferably daily, practice of the appropriate movement patterns is the best way.

Education in nurseries and primaries today has a large practical component. ‘Handling materials’, ‘investigating’, ‘problem-solving’ – these kinds of learning experiences permeate the curriculum beyond the nursery. Emphasis is always placed on handwriting skills so children who find moving difficult may be unable to function as well as their intellectual capacity should allow. For how can children with poor muscle control in their upper limbs learn to write? Motor problems can easily confuse adults into thinking that young children who may be reluctant to explain or who may be confused by not understanding their difficulties, are of a lower ability than is the case.

Before we begin to consider movement difficulties, it is a good idea to identify what is involved in moving well, because moving efficiently and effectively in different environments tends to be taken for granted with few people really appreciating the complex interplay of intellectual and motor abilities which occurs.

For moving well means:

- being balanced, i.e. stable in movement and stillness

- having a good sense of body awareness

- controlling the body as it moves

- coordinating different body parts so that movement is smooth

- gauging the correct amount of strength and speed

- understanding directionality

- being able to manipulate objects

- appreciating the rhythm of movements to ease fluency and repetition

- making safety decisions about when to move and where to move, and

- being able to stay still.

And these competencies depend on:

- being able to pay attention

- being able to remember what to do, and

- being able to use feedback from one attempt to improve the next try

A complex achievement, is it not?

When does it all begin?

From about four months after conception, mums are asked, ‘Have you felt the baby move?’ And an affirmative answer assures that all is well. We know that babies hear and taste in the womb. Could they be learning about movement as well? Yes, as they kick to strengthen their limbs they are learning about distance and direction and body boundary, i.e. where they end and the outside world begins. These are important stepping stones for later spatial decision-making. The kicking practice also means that all newborn babies can swim, the passageways to the lungs closing to prevent drowning, but unfortunately this primitive reflex fades away. From their very earliest post-natal days, children are constantly learning to move and moving to learn, and this learning means that all aspects of development constantly change.

Reaching and grasping

Picture Ellen, a baby of four months or so lying in her cot with a mobile suspended above her. She is fascinated by the bright colours of the toy and follows it with her eyes as it swings. She reacts by moving her arms and legs in a random uncoordinated way and by chance a hand strikes the mobile. This happens again and again and gradually Ellen comes to realise that she has caused the toy to move. She practises this until she can reach more accurately. At the same time her crooning noises attract Mum who is delighted with Ellen’s progress and she gives her daughter a hug.

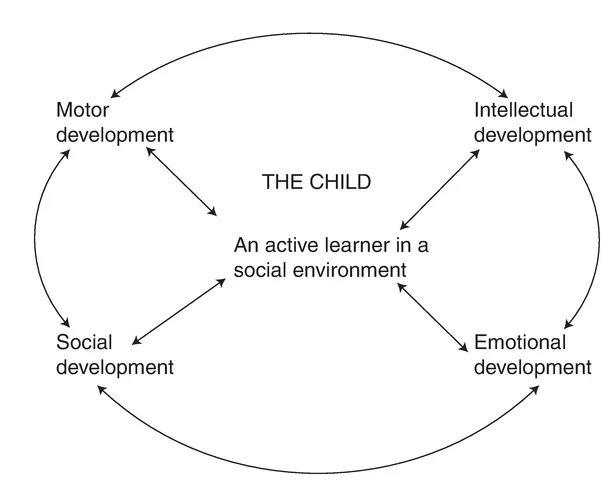

Dividing development up under the headings motor, intellectual, social and emotional is really a ploy to make the study of development manageable, for it is a huge topic covering many fields. Each aspect has its own specialist body of knowledge, but of course children don’t develop in discrete pathways – development in one area affects all of the others, some more, some less (see Figure 1.1).

Two examples will try to show this interdependency.

What has Ellen learned so far? Well, in reaching out she has learned that her hand could make things happen, about how far away the mobile was, what direction her stretch needed to have and where her own body finished and the outside object began. These are elementary kinesthetic learnings – body awareness, spatial awareness, directionality and body boundary, which are primarily concerned with motor learning but a great deal of intellectual gain has been made as well. For Ellen has been learning elementary tracking, i.e. following an object along a pathway, a skill she will develop in reading later on. She has also been learning what happens to an object when it is touched, a very early lesson in cause and effect.

Then her mum’s reaction helped her emotional development. She realises that she has pleased her mum and the hug she received reinforced the idea that it was good for her to try again. And so moving had also helped communication, an aspect of social development.

Now Ellen wants to have the toy. At first her striking actions are too hard and the toy swings out of reach, but gradually she learns how much strength to use and as the toy strikes her palm, she begins to time and refine the grasping action. Now she has it, but can’t let go. Letting go is a much more sophisticated action which needs lots of practice, but babies are motivated – they are skill hungry and she will persevere.

Figure 1.1 The interplay of different aspects of development

Grasping the toy is a significant achievement for Ellen and again this brings forth praise from her parents who are anxiously noting and applauding her progress in achieving her motor milestones. Moreover, she realises that she can move her arm and hand independently; she doesn’t require a whole body movement to accomplish her task. This is an important step towards using segmented, precise movements rather than whole body movements, which are cumbersome and inefficient.

She enjoys doing things well and as a result her confidence rises. Her emotional development has been strengthened again. And certainly others will come to admire her and so she learns to enjoy being the centre of attention. Perhaps she even learns how to control her audience by crying when they move away. Intellectual? Social? Emotional? Perhaps all of them, and all coming from a movement base.

Crawling

Many of the parents in the research said that their children had not crawled. Ben’s Dad, James, explained, ‘At the time, we didn’t think not crawling was significant, in fact we thought Ben had been quite smart and missed a stage out, but when we met other people and chatted about Ben’s difficulties, they invariably asked, “Did he crawl?”’ And so James wanted to find why crawling was so important and what vital learning the children who didn’t crawl had missed.

First, crawling is a form of locomotion or travelling and being able to crawl means that the children can explore their environment. For the first time they are in charge of making decisions about when to move, where to go, how fast to travel and what problems, such as emptying cupboards, they have to solve. And so the child has a measure of independence and this builds confidence as well as competence.

Some children move around by rolling over and over or by ‘bum-shuffling’, but learning to crawl using the cross lateral pattern has other benefits. First, the children who crawl take up a prone kneeling position and this helps strengthen the muscles around the shoulders and hips. They will be a little unsteady at first and fine adjustments are needed to hold the position. This all helps body awareness and the developing sense of balance. Then, as one arm is raised to stretch out, balance has to be held on three points, and more subtle adjustments have to be made. The extended arm investigates direction and distance, and these are important learning experiences for understanding positions in space.

The actual cross lateral crawling action is a complex sequence of movements where the arms and legs work in opposition. This patterning and coordination sets up a template in the brain which speeds up later learning. It promotes other forms of sequential activities, e.g. sequencing and ordering. These are important in learning to count and understand the logic of ‘beginning, middle and end’ in storytelling. A vast amount of motor and intellectual learning has been eased by children who have learned to crawl.

But what about the social and emotional aspects of development? Well, a great deal of confidence is gained from being independent, provided of course that there are not too many unsupervised bumps, and socially the children are able to move to join in games with others, perhaps even initiating a chasing game. Even very basic games have social parameters, e.g. turn-taking and looking out for others, and intellectual demands, e.g. empathising with the others, possibly non-speaking players, appreciating what they do, then planning an appropriate movement response.

If children don’t do these kinds of activities, they are missing valuable learning opportunities in all aspects of their development. And if they don’t attempt them at the right time – what some authors, e.g. Winston (2004), claim as ‘the critical learning time’ – they may be disinclined or be unable to try later. He is suggesting that the acquisition of skills is age-related, a claim that supports the emergence of motor milestones being ‘the same for all children in all cultures’ (Trevarthen 1977) (Appendix 1). However, there may also be psychological reasons why activities can be avoided. An adult learning to ski may well be put off by the five-year-old skimming past.

If you look back at Figure 1.1 now, you will see that at the centre is ‘the active child in a social environment’. These words were chosen to remind us that each child is a lively, usually social young person who will interact with his or her environment in a different way. Children are not passive recipients of other people’s learning. They actively seek out experiences that will help them to understand their world. From the start, they are problem-solvers who test out hypotheses, or ideas about how things might work, and they store the solutions in their memories. In this way they build a repertoire of skills, hopefully in a well-supervised safe environment.

This uniqueness means that each child will react in different ways, partly due to their individual personality characteristics. Many children with dyspraxia appear fearless and have to be watched every moment they are awake. They need ‘angels watching over them’, while others ponder, seemingly weighing up the likely consequences of what they might do. Others might decide to do nothing at all. Individual personality characteristics, such as resilience or vulnerability, influence how well the children with dyspraxia are able to overcome their difficulties. Vulnerable children can be devastated by happenings which the resilient ones manage to shrug off, apparently unconcerned and ready to overcome any obstacle which gets in their way. Highly motivated children will be more likely to succeed than those with a laissez-faire attitude. and of course, the children will be greatly influenced by their home environment; perhaps in the value they place on different kinds of activities, on taking risks – even on wanting to learn.

Lack of safe outdoor play spaces and lack of time to let children experience climbing and free imaginative play have contributed to a society where children are suffocated by adults who often feel guilty because of their absence and overcompensate by buying ‘p...