- 592 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Geomorphological Techniques

About this book

The specialist contributors to Geomorphological Techniques have thoroughly augmented and updated their original, authoritative coverage with critical evaluations of major recent developments in this field. A new chapter on neotectonics reflects the impact of developments in tectonic theory, and heavily revised sections deal with advances in remote sensing, image analysis, radiometric dating, geomorphometry, data loggers, radioactive tracers, and the determination of pore water pressure and the rates of denudation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.1

Methods of geomorphological investigation

1.1.1 Changing scientific method within geomorphology

The main concept of William Morris Davis was to arrange landforms into a cycle of development. His legacy was a concern with historical theory, which lasted until the 1950s (Chorley 1978). Despite claims by some commentators that more recent changes have been essentially incremental (Stoddart 1986), it seems quite clear that there has been a ‘revolution’ within the science of geomorphology over the last three decades. Following Kuhn (1962), Cohen (1985, p. 41) suggests several criteria by which a revolution may be seen to have occurred: ‘these include conceptual changes of a fundamental kind, new postulates or axioms, new forms of acceptable knowledge, and new theories that embrace some or all of these features and others’. Following the research of Horton (1945) and Strahler (1950), geomorphologists have developed a radically different framework for their science into which knowledge about landforms can be put. This recent work centres on the study of contemporary processes, a topic neglected by Davis. Geomorphology has become overtly ‘scientific’ in that the deductive route to explanation is followed (see below). This has entailed the adoption of quantitative techniques and mathematics within the subject, and has established experiment and observation as the basis of our knowledge. Thus, it is perhaps only natural that there has been much effort devoted to the invention, development and use of measurement techniques over the last 30 years.

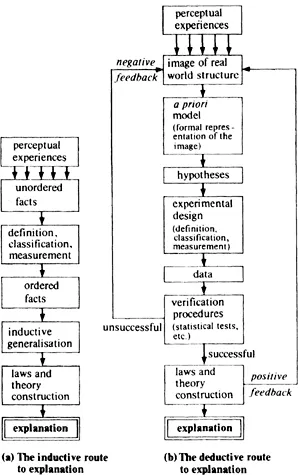

The abandonment by most geomorphologists of the Davisian model, and its attendant concern with denudation chronology, in favour of a process-based approach, has carried with it an implicit change in the mode of scientific explanation employed. The aim of scientific explanation is to establish a general statement that covers the behaviour of the objects or events with which the science in question is concerned, thereby enabling connection to be made between separate known events and reliable predictions to be made of events as yet unknown. During the development of modern science, two very different methods have been followed in order to arrive at a satisfactory scientific explanation (Fig. 1.1); a clear distinction exists between these two routes of induction and deduction. In the inductive or ‘Baconian’ approach, generalisations are obtained through experiment and observation. The final explanation is greatly dependent on the data that become available to the investigator, since these facts cannot be divorced from the theory (i.e. explanation) that is eventually produced. The process of classification is a central mechanism within this approach, since the explanation depends entirely upon the grouping procedure employed. The inductive approach thus rests heavily both on the data available and on the conceptual basis used to classify those data, and, even though a general model may exist within which reality may be viewed, many individual explanations remain a classification of the unique data set rather than a verification of the model itself.

The domination of Anglo-American geomorphology in the earlier part of this century by the concept of the Davisian cycle ensured that the classification procedure was dominated by considerations of time and the evolutionary stages of landform development. Thus, the division of landscapes into ‘youthful’, ‘mature’ and ‘old’ immediately prejudiced the explanation of the landscape since it assumed that a continuous process of erosion was involved, with each part of the landscape passing through each stage of development. In essence, time itself is seen as a process, indeed as the explanatory variable. Harvey (1969b, p. 424) notes that the assumption of time as a process is reasonable only if the process producing change is known, but frequently within the Davisian cycle the processes operating were not understood in detail. Moreover, the mechanism producing change must act continuously to allow the whole landscape to pass through the necessary sequence of stages. However, it often proved difficult to locate landforms into an ‘exact’ stage, especially where interruptions in the cycle had occurred. Indeed, the explanations produced by denudation chronologists illustrate only too well that interruptions in the cycle can occur so often that the explanation of a particular suite of landforms becomes very much concerned with a unique sequence of events, rather than with the application of the universal (classificatory) model. The temporal mode of explanation is not invalid methodologically, but it does require a process to act clearly and continuously through time and also demands an exact definition of the individual stages so that any particular situation may be located within them. However, as noted above, these requirements were generally not met by the Davisian approach (although perhaps ironically, as noted below, computer simulation models adopt such assumptions in order to allow retrodiction or prediction of landform evolution). It was gradually realised that what was important was not that change was occurring, but rather the following questions. What were the processes inducing change? At what rate did these processes act? And what effect did this activity have on the form and evolution of the landforms being considered? Thus, the temporal mode of explanation in geomorphology proved a poor mechanism with which to classify the unordered data being used in the inductive scientific model, and, because of the weaknesses inherent in the Davisian cycle, there was no proven unifying theoretical structure within which the individual explanations could be embraced. The trend towards a more detailed consideration of process-response systems was accompanied therefore by the abandonment of both the temporal mode of explanation and the inductive scientific approach with which it was associated. Geomorphology thus moved away from being essentially a classification procedure and adopted a radically different method of investigation based on the use of the deductive scientific method.

Figure 1.1 The routes to scientific explanation. (After Harvey 1969b).

The adoption of the deductive scientific method can be seen as both a cause and an effect of recent trends in geomorphology. By the early 1950s, the Davisian cycle had become more than simply a model of reality, and formed a paradigm within which geomorphological problems could be organised. However, as Kuhn (1962) points out, any paradigm that leaves unanswered more than it successfully explains leaves itself open for replacement by a completely new approach. The advent of the new paradigm was heralded by the introduction of quantification into geomorphology and by the adoption of statistical analysis as a means of testing hypotheses (Strahler 1950, Melton 1957, Chorley 1966). Implicit in the quantitative approach is the use of the deductive scientific method (Fig. 1.1b) whereby a theoretical approach to landscape form and development has replaced the elucidation of unique landform sequences which was dominant during the denudation chronology era. This theoretical approach is dependent on the formulation of an idealised view or model of reality. Such models may then be tested, either to confirm that they are indeed an acceptable (if ideal) reflection of the real world, or, if this is not the case, so that they may be revised and improved so as to become one. The testing of a model involves the independent collection of data. Thus, explanation of individual objects or events becomes, under the deductive approach, a more efficient process since general statements are produced to cover all such events, rather than producing a unique explanation based on the objects or events themselves.

The deductive route depends on a clear distinction between the origin and testing of theories: only the latter is based upon observation and logic. Popper (1972) has argued that the purpose of scientific experiments is to attempt to falsify theories: the best established are those which over a long period have withstood a gruelling procedure of testing. By ruling out what is false, a theory approaches the truth: though supported, it is not conclusively ‘proven’ since it remains possible that an alternative is a better explanation. Such an approach comes close to the deductive route proposed by Harvey (Fig. 1.1), notwithstanding semantic arguments over the difference between ‘falsification’ and ‘verification’. Even so, as Burt and Walling (1984) point out, the deductive route to explanation is more complex than Harvey (1969b) implies. Initial structuring of the model will depend in part upon the operational constraints known to apply—what experiments are required, what instruments or techniques are available, what field or laboratory facilities exist. The ideal separation of theory and fact may not initially be possible, therefore. Failure of an experiment may not condemn the theory; rather the experiment itself may be judged deficient in some way. In this case, the ‘unsuccessful’ feedback loop (Fig. 1.1) should stop at the experimental design stage; a new measurement technique may be required before the theory can be adequately tested. Strict formulation of an ‘experiment’ may not always be possible either. As noted below, many geomorphological studies do not constitute experiments sensu stricto, particularly in the early stage of theory development (Church 1984). It is clear, therefore, that neither the theory nor the experimental design is likely to remain static.

The new quantitative geomorphology has been very much concerned with elucidation of the relevant geomorphological processes and with considerations of the rates at which such processes operate. From knowledge gained about process activity, it has been possible to theorise on the landforms that should be produced by such processes. Certainly one major result of process study has been the relegation of time to the position of a parameter to be measured rather than as a process in its own right. Another major result of the change in geomorphological emphasis has been a reduction in the spatial and temporal scales within which landforms are now considered. The scale of landforms being examined has been reduced, partly because process and form are best related at small scales and partly because, over the large scales with which the denudational chronologists were concerned, process operation is not invariate as Davis envisaged but different processes have been seen to operate at different locations in a catchment (Dunne & Black 1970). In the early 1930s, it was not unusual for whole regions to be considered in one paper (e.g. Mackin 1936), whereas more recently, in fluvial geomorphology for example, landforms are considered at no more than the scale of a drainage basin (Chorley 1969), and frequently at a far smaller scale: for instance, differences between the processes operating on individual hillslope segments have been identified (Anderson & Burt 1977).

Schumm (1977a) has, however, augmented the Davisian model of landscape evolution by relating field and laboratory investigations to the mechanisms of long-term landscape change. It is argued that thresholds exist in the drainage basin system; channel pattern change associated with changing flume channel slopes is one such example, with meandering thalwegs introduced only at a threshold slope (Fig. 1.2). Evidence of this form has led Schumm to propose the replacement of Davis's progressive change notions of landscape change by the inclusion of episodes of adjustment occasioned by thresholds—a model stressing episodic erosion resulting from the exceeding of thresholds. Figure 1.3 illustrates the nature of the Davisian model modification, as proposed by Schumm, with the inclusion of the concept of ‘dynamic’ metastable equilibrium, or thresholds.

Of course, evidence of long-term landform development stems not only from contemporary laboratory investigations but from other more qualitative areas, too. Geomorphological systems are not only complex, but our knowledge of them becomes less exact as we move away from the present into the recent past. Environmental change, especially since the Pleistocene, represents a second major line of enquiry into the processes of long-term landscape change. Knowledge of such geomorphological indicators as those given in Table 1.1 can provide a most significant base from which to assess and explain aspects of change. Chandler and Pook (1971), for ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the first edition

- Preface to the second edition

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors

- PART ONE: INTRODUCTION

- PART TWO: FORM

- PART THREE: MATERIAL PROPERTIES

- PART FOUR: PROCESS

- PART FIVE: EVOLUTION

- References and bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Geomorphological Techniques by Andrew Goudie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.