- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

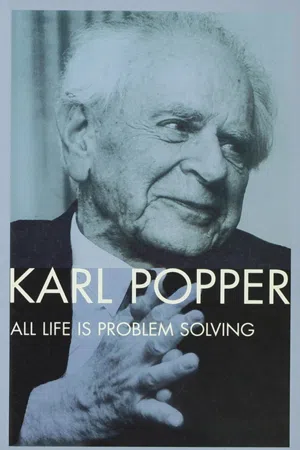

All Life is Problem Solving

About this book

'Never before has there been so many and such dreadful weapons in so many irresponsible hands.' - Karl Popper, from the Preface

All Life is Problem Solving is a stimulating and provocative selection of Popper's writings on his main preoccupations during the last twenty-five years of his life. This collection illuminates Popper's process of working out key formulations in his theory of science, and indicates his view of the state of the world at the end of the Cold War and after the collapse of communism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & TheoryPart I

Questions of Natural Science

1

The Logic and Evolution of Scientific Theory*

The central idea I should like to present in this talk may be expressed in the following way.

The natural as well as the social sciences always start from problems, from the fact that something inspires amazement in us, as the Greek philosophers used to say. To solve these problems, the sciences use fundamentally the same method that common sense employs, the method of trial and error. To be more precise, it is the method of trying out solutions to our problem and then discarding the false ones as erroneous. This method assumes that we work with a large number of experimental solutions. One solution after another is put to the test and eliminated.

At bottom, this procedure seems to be the only logical one. It is also the procedure that a lower organism, even a single-cell amoeba, uses when trying to solve a problem. In this case we speak of testing movements through which the organism tries to rid itself of a troublesome problem. Higher organisms are able to learn through trial and error how a certain problem should be solved. We may say that they too make testing movements – mental testings – and that to learn is essentially to try out one testing movement after another until one is found that solves the problem. We might compare the animal’s successful solution to an expectation and hence to a hypothesis or a theory. For the animal’s behaviour shows us that it expects (perhaps unconsciously or dispositionally) that in a similar case the same testing movements will again solve the problem in question.

The behaviour of animals, and of plants too, shows that organisms are geared to laws or regularities. They expect laws or regularities in their surroundings, and I conjecture that most of these expectations are genetically determined – which is to say that they are innate.

A problem arises for the animal if an expectation proves to have been wrong. This then leads to testing movements, to attempts to replace the wrong expectation with a new one.

If a higher organism is too often disappointed in its expectations, it caves in. It cannot solve the problem; it perishes.

I would like to present what I have said so far about learning through trial and error in a three-stage model. The model has the following three stages:

- the problem;

- the attempted solutions;

- the elimination.

So, the first stage in our model is the problem. The problem arises when some kind of disturbance takes place – a disturbance either of innate expectations or of expectations that have been discovered or learnt through trial and error.

The second stage in our model consists of attempted solutions – that is, attempts to solve the problem.

The third stage in our model is the elimination of unsuccessful solutions.

Pluralism is essential to this three-stage model. The first stage, the problem itself, may appear in the singular; but not the second stage, which I have called ‘attempted solutions’ in the plural. Already in the case of animals we speak of testing movements, in the plural. There would be little sense in calling one particular movement a testing movement.

Stage 2, the attempted solutions, are thus testing movements and therefore in the plural; they are subject to the process of elimination in the third stage of our model.

Stage 3, the elimination, is negative. The elimination is fundamentally the elimination of mistakes. If an unsuccessful or misguided solution is eliminated, the problem remains unsolved and gives rise to new attempted solutions.

But what happens if an attempted solution is eventually successful? Two things happen. First, the successful solution is learnt. Among animals this usually means that, when a similar problem appears again, the earlier testing movements, including unsuccessful ones, are briefly and sketchily repeated in their original order; they are run through until the successful solution is reached.

Learning means that unsuccessful or discarded solutions drop more and more to the level of passing references, so that eventually the successful attempt at a solution appears to be almost the only one left. This is the elimination procedure, which depends upon a pluralism of attempted solutions.

The organism may be said to have thus learnt a new expectation. We may describe its behaviour by saying that it expects the problem to be solved through testing movements and, in the end, through the final testing movement that is not eliminated.

As we shall soon see, the development of this expectation by the organism has its scientific counterpart in the formation of hypotheses or theories. But before I turn to the formation of scientific theories, I should like to point out another biological application of my three-stage model. My three-stage model,

- the problem;

- the attempted solutions;

- the elimination,

may also be understood as the schema of Darwin’s theory of evolution. It is applicable not only to the evolution of the individual organism but also to the evolution of species. In the language of our three-stage model, a change in either the environmental conditions or the inner structure of the organism produces a problem. It is a problem of species adaptation: that is, the species can survive only if it solves the problem through a change in its genetic structure. How does this happen in the Darwinian view of things? Our genetic apparatus is such that changes or mutations occur again and again in the genetic structure. Darwinism assumes that, in the terms of our model, these mutations function as Stage 2 attempted solutions. Most mutations are fatal: they are deadly for the bearer of the mutation, for the organism in which they occur. But in this way they are eliminated, in accordance with Stage 3 of our model. In our three-stage model, then, we must again stress the essential pluralism of the second stage of attempted solutions. If there were not very many mutations, they would not be worth considering as attempted solutions. We must assume that sufficient mutability is essential to the functioning of our genetic apparatus.

Now I can finally turn to my main theme, the theory or logic of science.

My first thesis here is that science is a biological phenomenon. Science has arisen out of prescientific knowledge; it is a quite remarkable continuation of commonsense knowledge, which may in turn be seen as a continuation of animal knowledge.

My second thesis is that our three-stage model is also applicable to science.

I mentioned at the outset that, as the Greek philosophers already saw, science starts from problems, from amazement about something that may be quite ordinary in itself but becomes a problem or a source of amazement for scientific thinkers. My thesis is that each new development in science can be understood only in this way, that its starting point is a problem or a problem situation (which means the appearance of a problem in a certain state of our accumulated knowledge).

This point is extremely important. The old theory of science taught, and still teaches, that the starting point for science is our sense perception or sensory observation. This sounds at first thoroughly reasonable and persuasive, but it is fundamentally wrong. One can easily show this by stating the thesis: without a problem, no observation. If I asked you: ‘Please, observe!’, then linguistic usage would require you to answer by asking me: ‘Yes, but what? What am I supposed to observe?’ In other words, you ask me to set you a problem that can be solved through your observation; and if I do not give you a problem but only an object, that is already something but it is by no means enough. For instance, if I say to you: ‘Please look at your watch’, you will still not know what I actually want to have observed. But things are different once I set you the most trivial problem. Perhaps you will not be interested in the problem, but at least you will know what you are supposed to find out through your perception or observation. (As an example, you might take the problem of whether the moon is waxing or waning, or which town the book you are reading was published in.)

Why did the old theory wrongly think that in science we start from sense perceptions or observations, and not from problems?

In this respect, the old theory of science was dependent upon the commonsense conception of knowledge. This tells us that our knowledge of the external world is entirely derived from our sense impressions.

I generally have a lot of respect for common sense. I even think that, if we are just a little critical, common sense is the most valuable and reliable counsellor in every possible problem situation. But it is not always reliable. And in matters of scientific or epistemological theory, it is extremely important to have a really critical attitude to it.

It is obviously true that our sense organs inform us about the world around us and that they are indispensable for that purpose. But from this we cannot conclude that our knowledge begins with sense perception. On the contrary: our senses, from the point of view of evolutionary theory, are tools that have been formed to solve certain biological problems. Apparently, animal and human eyes developed so that living things that are able to change their position and move about may be warned in sufficient time of dangerous encounters with hard objects from which they might receive an injury. From the point of view of evolutionary theory, our sense organs are the outcome of a series of problems and attempted solutions, just as our microscopes or binoculars are. And this shows that, biologically speaking, the problem comes before the observation or sense perception: observations or sense perceptions are important aids to our attempted solutions and play the main role in their elimination. My three-stage model is thus applicable in the following way to the logic or methodology of science.

- The starting point is always a problem or a problem situation.

- Attempted solutions then follow. These always consist of theories, and these theories, being trials, are very often wrong: they are and always will be hypotheses or conjectures.

- In science, too, we learn by eliminating our mistakes, by eliminating our false theories.

Our three-stage model,

- problem;

- attempted solutions;

- elimination,

may therefore be applied in describing science. This brings us to our central question:

What is distinctive about human science? What is the key difference between an amoeba and a great scientist such as Newton or Einstein?

The answer to this question is that the distinctive feature of science is conscious application of the critical method; in Stage 3 of our model, the stage of error elimination, we act in a consciously critical manner.

The critical method alone explains the extraordinarily rapid growth of the scientific form of knowledge, the extraordinary progress of science.

All prescientific knowledge, whether animal or human, is dogmatic; and science begins with the invention of the non-dogmatic, critical method.

At any event, the invention of the critical method presupposes a descriptive human language in which critical arguments can take shape. Possibly it presupposes even writing. For the essence of the critical method is that our attempted solutions, our theories, and our hypotheses, can be formulated and objectively presented in language, so that they become objects of consciously critical investigation.

It is very important to appreciate the huge difference between a thought that is only subjectively or privately thought or held to be true, which is a dispositional psychological structure, and the same thought when formulated in speech (perhaps also in writing) and thus presented for public discussion.

My thesis is that the step from my unspoken thought: ‘It will rain today’ to the same spoken proposition ‘It will rain today’ is a hugely important step, a step over an abyss, so to speak. At first this step, the expression of a thought, does not seem so great at all. But to formulate something in speech means that what used to be part of my personality, my expectations and perhaps fears, is now objectively to hand and therefore available for general critical discussion. The difference is also huge for me personally. The proposition – the prediction, for example – detaches itself from me when it is formulated in speech. It becomes independent of my moods, hopes, and fears. It is objectified. It can be experimentally endorsed by others as well as by myself, but it can also be experimentally disputed. The pros and cons can be weighed and discussed. People can take sides for and against the prediction.

We come here to an important distinction between two meanings of the word knowledge [Wissen] – knowledge in the subjective and in the objective sense. Usually knowledge is thought of as a subjective or mental state. Starting from the verb form ‘I know’, one explains knowing as a certain kind of belief – that is, a kind of belief that rests upon sufficient reasons. This subjective interpretation of the word ‘knowledge’ has had too strong an influence on the old theory of science. In fact, it is completely useless for a theory of science, because scientific knowledge consists of objective propositions formulated in speech, of hypotheses and problems, not of subjective expectations or convictions.

Science is a product of the human mind, but this product is as objective as a cathedral. When it is said that a proposition is a thought expressed in speech, this is true enough but it does not focus sharply enough on its objectivity. This is connected with an ambiguity of the word ‘thought’. As the philosophers Bernard Bolzano and (following him) Gottlob Frege have particularly emphasized, we must distinguish the subjective thought process from the objective content or the logical or informational content of a thought. If I say: ‘Mohammed’s thoughts are very different from Buddha’s’, I am speaking not of the two men’s thought processes but of the logical content of the two doctrines or theories.

Thought processes may stand in causal relationships. If I say: ‘Spinoza’s theory was influenced by Descartes’s theory’, I am describing a causal relation between two people and stating something about Spinoza’s thought processes.

But if I say: ‘Spinoza’s theory nevertheless contradicts Descartes’s on several important points’, I am speaking of the objective logical content of the two theories and not about thought processes. The logical content of statements is what I have in mind above an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Publisher’s note

- Preface

- Part I: Questions of natural science

- Part II: Thoughts on history and politics

- Subject index

- Name index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access All Life is Problem Solving by Karl Popper, Patrick Camiller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.