1

UNEVEN DEVELOPMENT: THE CAPITALIST WHIRLPOOL

In the newly opened up countries the capital imported into them intensifies antagonisms and excites against the intruders the constantly growing resistance of the peoples who are awakening to national consciousness; this resistance can easily develop into dangerous measures against foreign capital. The old social relations become completely revolutionized, the age-long agrarian isolation of ‘nations without history’ is destroyed and they are drawn into the capitalist whirlpool.

(Hilferding, 1910)

INTRODUCTION

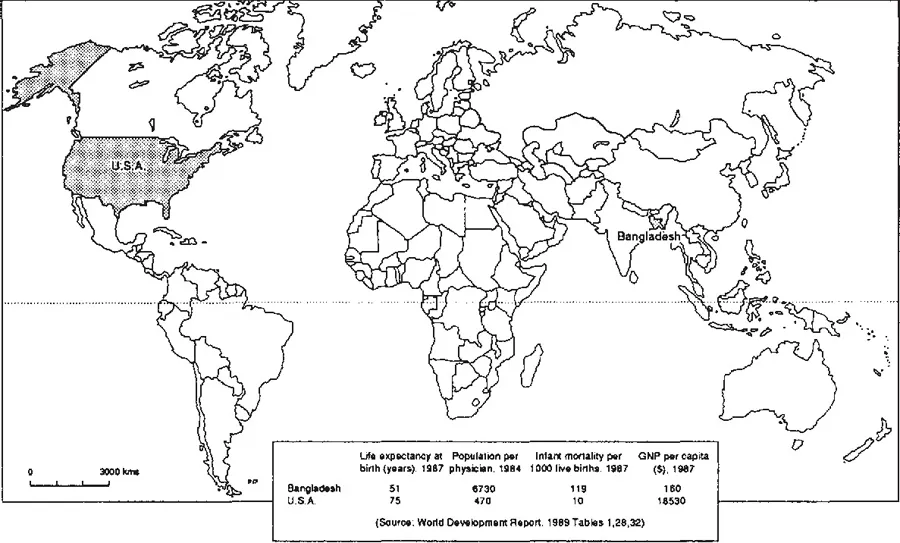

Figure 1.1 shows a range of data for Bangladesh and the USA. Behind these figures lie vastly different life experiences. In Bangladesh most people rarely live beyond 50, they have to share a physician with over 6000 other people and over 1 in 10 of their children die before reaching the age of 1. Compare that with the USA where the average person lives to be 75, most people have better access to medical care and are less likely to experience the agony of the death of a child.

Figure 1.1 Comparative statistics

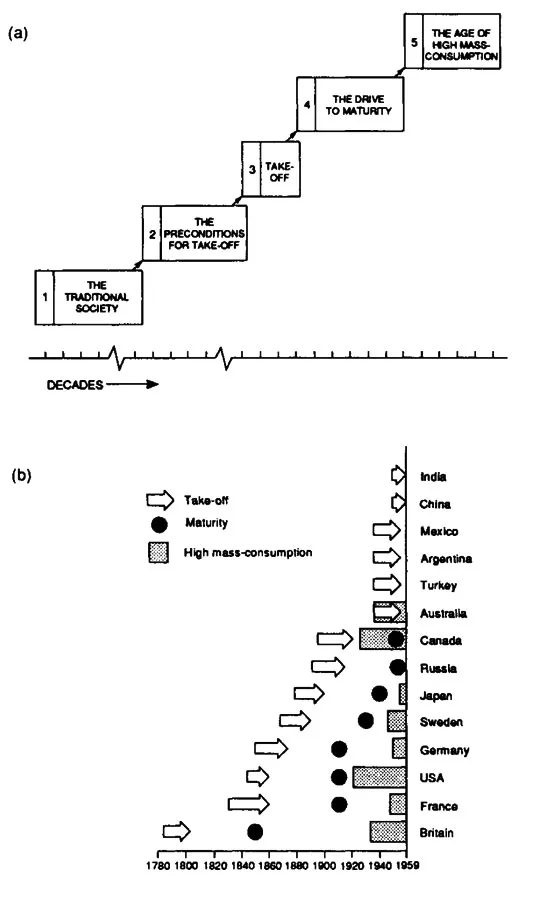

BOX A: THE ROSTOW MODEL

In outline the Rostow model identifies five stages to economic growth:

- Traditional society: characterized by limited technology, static social structure.

- Precondition take-off: rise in rate of productive investment and evolution of new elites

- Take-off: marked rise in rate of productive investment, development of substantial manufacturing sectors and emergence of new social and political frameworks which encourage and aid sustained economic growth.

- Drive to maturity: impact of growth affects the whole economy.

- Age of high mass-consumption: shift toward consumer durables.

The model has been used to describe the experience of selected countries (see Figure A.1). Criticisms of the model have centred on its inability to identify casual mechanisms between the different stages.

References

Baran, P.A. and Hobsbawm, E.J. (1961) ‘The stages of economic growth’, Kyklos 14, 324–42.

Rostow, W.W. (1960) Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Rostow, W.W. (1978) The World Economy. University of Texas Press, Austin and Landin.

BOX B: RICH AND POOR COUNTRIES

We have to be careful when we use the terms rich and poor when applied to whole countries. The reality is that there are rich people in poor countries and poor people in rich countries. Income is very rarely evenly distributed throughout the population.

Table B.1 Income distribution in three countries

Figure A.1 The Rostow model

These figures are the tangible effects of an uneven development in the world. Uneven in the sense of marked inequalities, development in the broad sense of economic growth and social progress. Bangladesh and the USA are at the two extremes of the continuum of uneven development, one very poor, the other very rich. They highlight the basic division of the world into rich and poor countries. This division has been given a variety of names—developed-undeveloped, First World-Third World, North-South. Whatever the labels used the basic question remains. How did it come about?

One model used to explain this variation has been put forward by the US economist W.W. Rostow. He argues that economic growth has been achieved by only a few countries. In the rest, however, once the barriers of traditional society are broken down, growth can be achieved, leading to the final stage of high mass-consumption: left to market forces and time all countries will look like the USA. Underpinning the model is the notion that the international trading system is a harmonious system in which all countries can benefit. The crucial policy questions of the Rostow model are: what are the best methods of establishing the preconditions for growth and how can economic take-off be achieved? Poverty in the Rostow view of things results from lack of involvement in world trade.

The alternative model, the core-periphery model, takes the very opposite stance: poverty arises from involvement with the world economy. The core-periphery model refers to the spatial division of the world and a set of economic relationships. The core consists of the rich nations— Japan, North America and Europe while the periphery consists of all other countries. This broad-scale division of the world economy marks off rich countries from poor, economically advanced from economically underdeveloped, dependent from relatively independent economies and economic development as growth from economic development as growing dependence. The rich countries of the ‘north’ constitute the core because the international economy revolves around them and they have been the moving force guiding the development of an integrated world economy. The ‘south’ is peripheral in the sense that its economies are articulated to the needs of the rich core countries and the pace and character of its development have been shaped by contactwith the core. There are, of course, elaborations to this simple structure:

- We can identify developed peripheral economies such as Australia and South Africa where the extraction of minerals and the production of primary commodities has been associated with relatively high rates of internal economic growth and high average incomes.

- We can also identify semi-peripheral countries which have achieved some level of autonomous economic growth. Two types can be identified: countries such as Brazil, which have been moving in the direction of periphery to core, and countries such as Britain, which seem to be moving in the opposite direction, from core to periphery.

THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Beginnings of the world economy

The growth of the core-periphery structure of the world economy can be said to have started around 1500. That date marks the beginning of European overseas expansion and the articulation of an international economy based on flows of goods and people to and from Europe. The foundations for this expansion had been laid almost 350 years earlier. From about 1150 the increase in trade both within Europe and between Europe and the East saw the development of a merchant class, the growth of urban trading centres—Genoa, Venice, Naples and Milan in the south, the Hanseatic League towns of Hamburg, Lubeck and Bremen in the north—and the beginnings of money being used as a means of exchange. The merchants, the urban trading circuits and the use of money were essential prerequisites for the development of long-distance trade.

Between 1500 and 1600 European overseas expansion emanated from Iberia. The search for bullion, the demand for spices and the need for fuel (mainly wood) and food all gave impetus to exploration and when the Ottoman Empire obstructed overland trade with Africa and Asia, Iberia was well placed as a base for forging new trading links with the East. Portuguese merchants strung a number of trading posts along the main sea routes to Africa, India and the Far East and ships from Lisbon sailed regularly to Goa (India), Colombo (Sri Lanka), Malacca and Macao, collecting pepper, cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg. Contact in the East was limited to trade with the ports. The most important developments in colonization took place in the Americas. The Spanish first colonized the islands of the Caribbean in the late fifteenth century. Following the discoveries made by Cortes and Pizarro they then moved into Mexico and Peru. The Portuguese meanwhile obtained the eastern half of Brazil after the Papal settlement of 1493, which divided the New World between two Old World powers.

Throughout the sixteenth century the Americas were the scene of extensive exploitation as sugar plantations were created and the land was plundered for gold and silver. Both the mines and plantations used slave labour. Initially, the indigenous Indians had been used but the appalling fatalities and the increasing demand led to the growth of the slave trade. A rudimentary triangular trade was developed, with ships sailing from Europe to West Africa, taking slaves to the Americas and then returning to Europe with bullion and sugar. The sixteenth century thus witnessed the growth of the core-periphery structure from its early embryonic form. With the slave trade and the colonization of the Americas more of the world was brought within the orbit of Europe’s trade. There were also the beginnings of the international division of labour, with slave labour in the Americas providing primary commodities for European markets. The gold and silver from Central America which flowed through the trading arteries of European merchant cities allowed the accumulation of money and commercial capital which eventually was to lay the basis for further economic growth. The plunder from the Americas provided the basis for investment in the early manufacturing industries of Europe. The nature and the timing of the incorporation of American territories into the European world economy was to determine the subsequent development of these areas.

By the beginning of the seventeenth century both Spain and Portugal were being hard pressed by other European powers. From 1600 onwards the power of Spain and Portugal began to decline as the struggle for commercial mastery was disputed between Holland, Britain and France. The centre of gravity in the core was beginning to shift.

The sharpening of conflict arose as the suckers of trade, which stretched out from the various countries, overlapped and struggled for sustenance in the same areas of the world. The conflict was not restricted to the commercial rivalry between the great trading companies. Commercial rivalry escalated into conflicts between states as each nation began, in varying degrees, to accept the mercantilist idea that it was the business of the state to promote the economic interests of the country and that this could best be achieved by stimulating foreign trade. For the mercantilists, foreign trade was seen as the chief method of increasing national wealth. Initially, it was thought that the best way to increase wealth was to accumulate gold and silver; the Spanish overseas expansion in the sixteenth century was partly grounded in this belief. Eventually, the emphasis changed to a belief in the efficacy of the import of raw materials and the export of manufactured goods. The state was called upon to achieve conditions favourable to the balance of trade, for as Thomas Munn counselled in 1622: ‘We must ever observe this rule: to sell more to strangers yearly than we consume of theirs in value’ (quoted in Rude, 1972, p. 267). Favourable conditions of trade meant that the continued supply of raw materials had to be assured and markets for finished goods had to be made safe from foreign competition.

The mercantilists believed that the world’s total wealth was fixed in quantity like a giant wealth cake and could not be increased; any increase in one nation’s slice of wealth could only be achieved at the expense of others. It thus followed that the most favourable conditions of trade were achieved in colonial empires where the terms of trade were shaped for the benefit of the merchants of the (metropolitan) country. For the mercantilists, colonies were simply branch plants providing valuable commodities and offering secure markets. The overseas expansion of the core states in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was to all intents and purposes a commercial undertaking— an under-taking whose aim was to achieve a self-sufficient economic empire and whose driving force was mercantile capitalist.

The pace of colonial expansion and the size of colonial holdings were shaped by the changing balance of forces between the core countries and their commitment to overseas expansion. In the first half of the seventeenth century the Dutch were the most dynamic nation, their ships spinning a web of trading links as far as Indonesia, India and North and South America. The efficiency and aggression of the Dutch trading machine were the envy of Europe and when Louis XIV’s minister Colbert attempted to invigorate the French trading companies he modelled them on the Dutch. The solid faces which peer out from the canvases of Rembrandt, Vermeer and Hals belonged to the most aggressive merchants of their time. The success of the Dutch attracted the retaliatory action of other nations. In 1651 republican England passed the Navigation Act, which laid down the principle that trade with the colonies should only be carried on by English ships. The act was specially designed to defeat the Dutch hold over the shipping trade and to direct the valuable entrepot trade (the re-export of colonial commodities to Europe) towards England. The wars with Holland which followed this act and which lasted on and off from 1652 to 1674 were the military expression of the commercial rivalry between the two states. The ultimate English victory allowed English merchants to establish trading links ...