![]()

Part I

Urban Fallacies

![]()

Chapter 1

The Metropolis in the Twenty-First Century

Problem or Solution?

This is already the century of the metropolis. More than half the world’s population now lives in metropolitan regions. If current rates of growth continue, by the end of this century almost all people in the world will live in large cities. Everything will be urban and “rural” areas will be giant empty spaces—unpopulated enclaves of industrial agriculture, mining and forestry. Urban plannning, which in the twentieth century sought to solve urban problems, will be indistinguishable from all other professions seeking to improve the quality of human life. Every place will be “urban” and everyone wishing to improve the human condition will be an “urban planner.”

Should we mourn or celebrate this urbanization of the world? Are cities a problem or a solution to our problems? Are cities just giant wells of despair, inequality and environmental degradation or beacons of human hope, progress and healthier environments? Will they exacerbate climate change or prevent it?

Everyone interested in making a better world in the twenty-first century—the urban planners of the world—should first recognize that these are the wrong questions. We will see in this chapter how cities are neither the problem nor the solution. They are places where both problems and solutions are located, and much more. We ask the wrong questions because too often we have a distorted view of the metropolis and the world, one that is bound by the histories of colonial and imperial relations and our own limited experiences. We are looking only on the surface and not paying enough attention to the growing segregation and inequalities within and among urban areas—that is, in the entire world. Especially during this period of global economic crisis, we also fail to make the connections between global capitalism, climate change, the abandonment of rural areas and urbanization. To focus on the metropolis in the century of the metropolis is to undertake the incredibly difficult and complicated task of understanding the multiple dimensions of everything going on in the human world.

The modern metropolis was born in the last century and is still relatively young. In the more than two millennia since the first human settlements appeared on the earth, most people lived in rural areas, small towns and cities. There were never more than a few giant cities with a population of over a million people—for example, imperial Rome and Beijing. By the year 2000, however, there were some 500 metropolitan areas, most of which formed in the twentieth century. The metropolis flourished in every region of the world, rich and poor, north and south, east and west. The twentieth century brought on an urban revolution and its product was the modern metropolis.

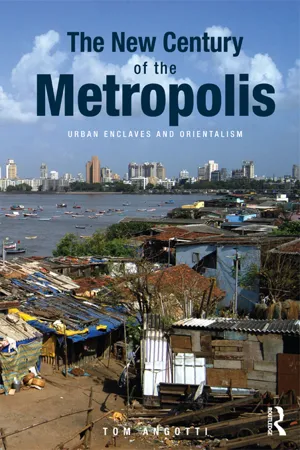

The majority of urban dwellers today live in Africa, Asia and Latin America, in metropolitan regions that are not well understood in the “developed” world, where most of the theories about urbanization and the practices of urban planning come from. These theories and practices are based on giant myths describing the “underdeveloped” metropolis as a giant, homogenous landscape of chaotic, unsanitary, and dangerous “slums.” The myths treat the people who live and work in these cities—that is, most of the urban dwellers in the world—as a single undifferentiated mass of poor people. The poor “slum” dwellers are a vaguely defined “other.” This mythology leads to real world policies that blame the other for urban problems and effectively make things worse for them. As we show throughout this chapter and book, the problem is not the city or its population but the capitalist economic and social relations that are its foundation. To address urban and environmental problems we must first understand and change these relations.

In the twenty-first century, if metropolitan regions continue to expand at the current pace (although that is by no means a certainty) by the end of this century almost all of the world’s population could reside in large cities. This would culminate in the historic transformation of the world from a rural to urban one. However, this great transformation coincides with other unprecedented trends in human history: global climate change, sea level rise, deforestation, the accelerated extinction of species, food insecurity, and the alienation of human society from the natural world. These environmental challenges raise serious questions about the capacity of humans to sustain themselves beyond this century on the earth, which after all has been around for billions of years, most of them without humans. In Collapse, Jared Diamond alerted us to the historic precedents of societal collapse which occurred when people were unaware how their relationship to the local environment was eroding their resilience. While the environmental and public health problems of this century might be mitigated by new technologies and practices, the most powerful economic regimes in the world, and the military machines that protect them, may make it impossible to move beyond mitigation to survival. Indeed, underlying the environmental crises is an even greater crisis—the global meltdown of finance capital, particularly since the latest crash in 2008. This deep cyclical downturn has opened our eyes to the interconnections between urbanization, climate change and the global commodification of land, water, and all that can be commodified, deepening the stark partition between urban and rural areas that originated with industrial capitalism and the modern metropolis.

To get to the heart of the urban question in the twenty-first century, therefore, we need to dig deeply into all aspects of human society and nature—economic, social, and political. As a first step, we will need to dispose of the many fallacies and prejudices that keep us from getting at the roots and developing strategies for the future. The first fallacy is the urban fallacy.

The Urban Fallacy

Aren’t giant cities responsible for at least some of the planet’s economic and environmental problems? After all, big cities consume more energy and goods and are responsible for most of the pollution and greenhouse gases in the world. They sap natural and human resources from rural areas. They concentrate capital, labor and power, and create enormous inequalities across physical space, between urban and rural areas and within cities. Aren’t cities by definition too large, dense, and conducive to social disorder? Don’t cities always breed poverty and concentrate it in huge “slums”?

This is the first part of the grand urban fallacy inherited from the twentieth century. Actually it was born at the cusp of the century, along with the moralistic Victorian notions of pathological poverty and the undeserving poor. It was given a political revival in response to the worldwide urban uprisings of 1968, with conservative voices like Edward Banfield arguing that the city created and reproduced anti-social behaviors in poor people and people of color. For years after this, the rhetoric about “slums” was rejected by many as racist and reductionist, but has now been brought back into the mainstream with “soft” declarations and new versions of global philanthropy. In 1999, the United Nations launched their “Cities Without Slums” initiative. In their 2003 document “The Challenge of Slums,” UN-HABITAT argued that past “slum up-scaling” projects failed because of a lack of sustained commitment and resources, without challenging the fundamentally flawed vision of the root causes of urban inequalities. UN declarations aside, however, the perception that cities breed poverty and social disorder is pervasive. Forbes Magazine, in a story on the global shift towards a majority urbanized world, declared bleakly, “the future of the city is a vast Third World slum.” This is the urban fallacy—and the world as seen by many in the global centers of wealth and power.

The other version of the urban fallacy says that cities are the solution, not the problem. The recent book by Edward Glaeser, Triumph of the City, argues that cities today are the best hope of humanity, “our greatest invention.” Even though most people living in cities lack decent housing and basic services, the standard of living in cities is generally better than in rural areas and cities have many more economic and cultural opportunities. Glaeser says the problem isn’t the size of cities or urban density; in fact the larger and more dense cities turn out to be wealthier, healthier and greener. Greater energy efficiencies are possible in cities and in some densely developed central cities people use less power and water and produce less waste.

However, while Glaeser helps debunk the myth that high urban densities necessarily produce social and environmental problems, and acknowledges the many urban problems around the world, he also sees the metropolis from the vantage point of the most powerful and privileged urbanites in the world, which leads him to overlook many inconvenient truths. It is a rosy picture of the city as seen from the central business districts of the world and their leaders like New York City’s billionaire mayor Michael Bloomberg, who are keen on saving energy, attracting more wealthy people, and branding their wealthy enclaves as attractive green destinations. There is a rising chorus of urban optimists who believe that trends are moving in the right direction and we need to encourage and emulate the greening of Manhattan. They say that because the standard of living in cities tends to be higher we will all be better off when we all live in cities; high-density living saves energy and makes for a greener planet; and cities are where new technologies and smart growth policies will have the greatest impact. However, this presumes that these benefits will be distributed equally and available to everyone in large and diverse metropolitan regions.

The urban fallacy is the notion that the world’s problems are caused by big cities or that they will be solved when everyone lives in big cities. This book aims to show that both versions of the urban fallacy fail to look at all the evidence and to understand cities in their broader historical and economic context. They overlook the underlying economic, social and political conditions that produce and reproduce cities. They do not probe the ways that capital and labor, and the relations between them, shape urban development and environmental and climate problems. I will argue that all urban planners in the twenty-first century should reject the urban fallacy, leave behind past idealized notions of the good and green city, and instead learn from the many grassroots alternatives offered by those who are struggling for their right to the city.

These are not abstract or theoretical issues. Our understanding of the role of cities is the foundation for global and local policies that affect people who live and work there and all living species on the planet. The optimistic view of the city supports public and private investments in cities, and efforts to make them greener and denser, and the pessimistic view leads to efforts to slow urban growth and redirect resources. But only a balanced view can help find ways to address the great political dilemmas of the new metropolitan century, including global climate change, environmental damage, and gaping inequalities—all of which will now be “urban.” The stakes are the highest. A failure to understand the perils and benefits of the current trajectory towards a completely urbanized world could leave us unprepared to avert the worst possible scenarios.

Before turning to a more detailed understanding of the urban fallacy in the twenty-first century, let us first look more carefully at this phenomenon of the modern metropolis and how it differs from previous forms of human settlement.

The Modern Metropolis

In his classic essay, “The Modern Metropolis,” Hans Blumenfeld called attention to this revolutionary transformation:

from its long, slow evolution the city has emerged into a revolutionary state. It has undergone a qualitative change, so that it is no longer merely a larger version of the traditional city but a new and different form of human settlement.

According to Blumenfeld, the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century “dramatically reversed the distribution of population between village and city.” The major force behind this was the “dual spur of specialization and cooperation of labor” which “started a great wave of migration from country to city all over the globe.” This centralizing tendency, however, was soon complemented by

an equally powerful centrifugal wave of migration from the city to the suburbs. Although … more and more of the population is becoming urban, within urban areas there is increasing decentralization. The interaction of these two trends has produced the new form of settlement we call the metropolis. It is no longer a ‘city’ as that institution has been understood in the past, but on the other hand it is certainly not ‘country.’

Why is Blumenfeld’s thesis so important? What difference does it make that the twentieth century metropolis was not only larger but a qualitatively new form of human settlement, and that it was much more complex than the company town and industrial city that preceded it? This is not an abstract question but especially critical for those who formulate strategies and undertake planning in the metropolis. A recurring thesis in this book is that the problem with planning is its reliance on traditional late nineteenth century Victorian, European and North American approaches to the much smaller industrial city. Orientalist planning is unable to confront the serious problems of the twenty-first century metropolis; indeed, it serves to reproduce them.

The metropolis everywhere is a center of economic and political power, as with all previous forms of human settlement. Its ruling elites exert a central leadership role in all economic activity. The metropolitan financial centers often include industrial production, but to widely different degrees. Many have become “post-industrial cities” (a misnomer because their financial institutions retain economic control over industrial production in other cities and nations). The metropolitan elites and their corporate entities do not have to compete with the agrarian sector and actually dominate it. The metropolis is a center of both national and international finance, controlling capital investment, savings and distribution. In the twentieth century the metropolis was the center of economic and political power in centrally planned and mixed economies as well as all capitalist economies.

Blumenfeld understood that the modern metropolis is composed of a complex of developed districts and open areas and has a well-developed division of functions. The spatial division of functions corresponds with the economic division of labor. There is greater mobility within the metropolis and more opportunity for a wider variety of social and economic activities. The metropolis has a more diverse geography and economy. It is subdivided into many large districts with diverse populations, economic activities and cultural functions, and there is greater mobility, both physical and economic, among the districts.

Complexity, diversity and mobility therefore make the metropolis more resilient and able to weather economic storms; it no longer depends on a single economic activity as did the mining, factory or mill towns that vanished. Its diversity is not only in production but also in consumption, and its wide array of services and cultural activities make it a magnet for residents and visitors. Complexity and diversity make the metropolis the most stimulating and exciting place for human interaction, including personal interaction, cultural activity, and commercial exchange. After all, human interaction has been the very heart and soul of urban life since the earliest human settlements made the nomadic life of hunting and gatherin...