eBook - ePub

Adjustment of Adolescents

Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book will make fascinating reading for anyone involved in the study of adolescence, or working with adolescents. The authors explore the transitions of school, family and personality in the contexts of family, friends and wider social factors. This exploration is based on original research carried out in Canberra, Winnipeg, Phoenix, Berlin, Hong Kong, Osaka and Taipei. The authors also provide valuable insights into the methodologies of cross-cultural study.

The perspectives of this book make it an ideal resource for undergraduates and masters students undertaking a cross-cultural study, which is becoming a mandatory part of many degree courses.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adjustment of Adolescents by W. A. Scott,William Scott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Background and Overview

One of the major challenges facing those living in technologically advanced societies is the need to adjust to various, and sometimes conflicting, social systems such as the family, friendship networks, work or school groups, and various traditional groups including the church which are oriented toward preserving cultural norms. At adolescence, the conflict among the demands of several groups is likely to be particularly acute, as increasingly autonomous children struggle to gain freedom from parents, to meet teachers’ demands for academic performance, to make and maintain friendships, and to find a place for themselves in society. For the most part, the family and the school are allied in their expectation of increasing social maturity through internalizing adult values. In contrast, the adolescent peer group may exert pressures antagonistic to these adult institutions, perhaps because children want more control over their own lives and judge the peer group to be more similar to themselves, and therefore more sympathetic to their interests, than the adult-dominated social order (Bronfenbrenner, 1970; Coleman, 1961).

What effect do these various demands have on the adolescent? Can we predict adolescents’ adjustment to their various areas of concern, which in this book include academic matters, interpersonal concerns and family relations? Do different judges (the self, parents, teachers, peers) evaluate the success of adjustment similarly? Are factors contributing to a successful adjustment in one situation, say the family, the same as those in another area? Finally, do these associations of adjustment generalize across cultures? These are the questions addressed in this book. Data have been collected on the adjustment of adolescents in seven different cultures. The general model posits that environmental conditions result in the individual adopting coping styles that subsequently shape his or her adjustment. In this chapter we will discuss the theoretical rationale for the model and the definitions of the environmental conditions, coping styles and adjustment outcomes, along with the previous work on which they are based.

Before we do this, a number of distinctive features about this broad gauge, cross-cultural research warrant discussion. First, this book proposes a psychologically integrated, as opposed to a compartmentalized, approach. Second, it pursues transcultural stability as the criterion for establishing variables as major predictors of adolescent adjustment. Third, it examines the adjustment of adolescents over different areas of concern, as seen not only through their own eyes, but also through the eyes of their significant others: parents, teachers and peers.

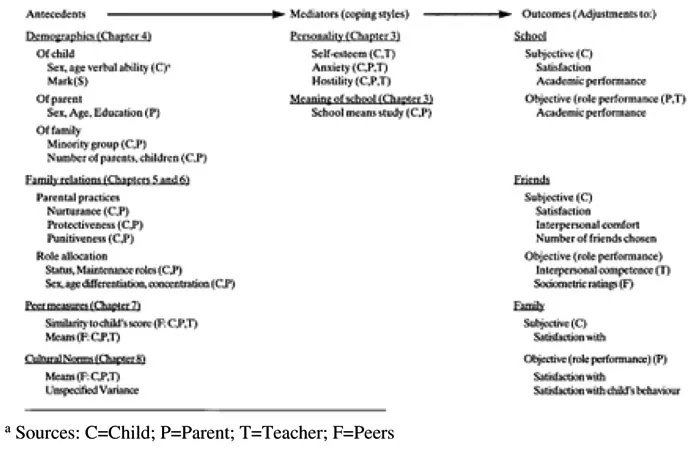

Figure 1.1 outlines our model. It also specifies the chapters in which each particular classification of variables is introduced. We will briefly present the measures we used to represent these concepts, as well as the work of others we used to guide our selection of variables. All descriptive data entered into our models are based on mean within-sample results collected from seven cities representing both Occidental and Oriental cultures, described in full in Chapter 2, and include the data from four perspectives: the child, his/her parent, teacher and classmates. All relational data are based on the total sample when the contribution of specific cultures has been partialled out.

Starting with Chapter 3, we describe the adjustment data, their interrelationships, and their relationship with the coping styles which we predict mediate the effect of the various classes of predictors. Though in this book we are emphasizing the gains that can be made by an integrative approach to data analysis, we introduce each type of data by first establishing the zero-order effects on our outcome adjustment measures and coping variables. This is followed by presenting their unique effects, represented by their beta weights in multiple regression analyses containing other significant predictors. Chapter 4 describes the effect of the significant demographic variables on the mediating and dependent variables. This is followed by the family variables, introduced into the model in Chapter 6 after being described in detail in Chapter 5, the peer variables (Chapter 7) and, finally the cultural variables in Chapter 8.

Adjustment Evaluated By Whom: The Source Effect

Success of the adjustment to social systems can be appraised both subjectively and objectively. By subjective adjustment we mean self-judged satisfaction with a particular domain of life; for adolescents, the three main foci for adjustment are defined as school, friends and family. By objective adjustment we mean the adequacy of the role performance in that domain, as judged by role partners. Adjustment to school may be appraised both as subjective satisfaction and, objectively, by others’ evaluations of the student’s academic performance. Adjustment to friends can be measured as subjective satisfaction with interpersonal relations, and objectively, by acceptance by others and their evaluations of the adolescents’ competence in these roles. Finally, adjustment to family can be represented both as satisfaction with other members and as their reciprocated satisfaction with the adolescent.

This study is distinctive in its attempt to map both the subjective and the objective adjustment of adolescents and the degree of similarity in their predictors using data collected from diverse sources; the child, the parent, the teacher and classmates. In general, there is a tendency toward convergence between subjective and objective adaptation within any particular domain. People who are performing well are likely to receive favourable feedback from their role partners, which enhances their self-esteem, and hence their satisfaction with the role system. Conversely, satisfaction with one’s colleagues in a role system is likely to encourage effort to perform to their satisfaction. A complementary reciprocity is likely to prevail among dissatisfied, inadequately performing members of a group as well. Negatively valued members tend to give up their role obligations, which further increases their alienation from the group.

FIGURE 1.1 Adolescent adjustment model: specification and classification of measures.

Adjustment to What: Situational Determinants

The terms adaptation and adjustment imply not only an adapting person, but a set of circumstances which impose demands and requirements. One adapts to school, to a wartime battlefield, to parenthood, to a poker club. To say that one becomes better adjusted risks a confusion between the individual and the situational component. The capacity to adapt to a wide range of situations may, indeed, facilitate success in numerous endeavours, but we find it clearer to conceive such a capacity as an aspect of personality, which provides only one part of the adaptive process. The other part, situational characteristics, is a necessary ingredient as well. It is quite easy to imagine a circumstance—such as oxygenless atmosphere or a totally unpredictable social environment—with which even the most hardy (adaptable) person could not cope. We conceive of adjustment as the contribution of the individual to adaptation that can be viewed by the self or others in a specific domain of activity.

While acknowledging that success generalizes to new areas of life and failure demoralizes, inhibiting or disorganizing action in other domains as well as the focal one, we assume at the outset a fair degree of domain specificity. In other words, it is quite possible for a person to do well in one area of life and poorly in others. Moreover, this conceptualization allows for the practice of individuals’ transferring effort and attention from the less to the more successful domains, thereby expanding their attention to new areas which look promising.

Adjustment Where: Cultural Contributions

Finally, the contribution of the culture in which the adolescent is embedded also plays a part in the child’s adjustment, both as viewed by the child and by role partners, such as family members, peers and teachers. By culture we mean the shared meanings among the individual members of the social groups as displayed by their expressed opinions and behaviours. It is now common to measure and compare opinions and behaviours across cultures, but the fact that there are rarely large numbers of cultures sampled limits the inferences that can be drawn from the data. Further limitations result from the use of opportunistic rather than theory-based selection techniques when picking the subjects. Within cultures, the use of equal-probability samples is rare, with university students usually the only population from which subjects are chosen. Differential restrictions between samples (cultures) have consequences for inter-cultural comparisons. One cannot infer an underlying basis for differences between two samples when the differences lie only in responses to specific scales or on the relationship between two variables, as there are too many other differences between the two societies, measured and unmeasured, that could also be the cause. However, if there is a common predictive model found within various cultures and these differences are also mirrored in mean differences between samples, then we are on firmer ground in interpreting cultural differences (see Scott, Scott, Boehnke, Cheng, Leung and Sasaki, 1991).

Here, we will first develop models predicting adjustment which hold within our seven cultures before examining the role cultural differences may play in influencing levels of adjustment. For instance, in our study, the very important relationship between high parental nurturance and high self-esteem scores is found within each sample. This finding also holds when comparing cultures; cultures with high mean parental-nurturance scores also have high self-esteem scores, as reported by the adolescents. This leads us to say that the cultural differences in self-esteem, an important mediator for subjective and objective school and friend adjustment, are based on cultural differences in parental nurturance.

Theoretical Framework: An Integrative Approach

Recently, there has been a trend to simplify research design and topics: to look at a single domain of predictors (e.g. friendship groups) with data collected from a single source (e.g. self-report) from one group of subjects (e.g. university students). Though undoubtedly this is in part a result of a need to refine theory and instruments, it is also driven by the need to publish in order to get promotion or a new grant. Even when databases exist allowing examination of many variables from more than one source, information about non-predicted variables, including those driven by instrument design (scale type and direction), are treated as extraneous noise, contributing to an increased error term, rather than as something which could add to the understanding of the outcome under study. Of course, longitudinal studies, or those requiring data collection from more than one source of subjects and more than one type of sample, require a time perspective beyond the reach of many current researchers.

In his 1936 book Topological Psychology, Kurt Lewin presented his formula for predicting behaviour as a function of personality and environment. Along with Cattell (1993) and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development, as reported by Jessor (1993), in this book we first call for a return to an integrative approach to research, whereby we increase our understanding of the relative influence of various domains of variables on predicting behaviour. Second, we hope this project will rekindle emphasis on the methodological effects of instrument construction, data source, and sample selection on designing studies (see Chen, Lee and Stevenson, 1995). Further, we hope this book will lead to more replication of relationships found within one culture to those in others. Most of the frameworks now driving social psychological research have been developed within the industrial Western culture, primarily the United States. Do these frameworks also predict behaviour in other, non-Capitalistic, non-Judaeo-Christian cultures? Would other variables increase the ability to predict behaviour in Oriental cultures? These are the questions one hopes future researchers will be addressing in greater numbers.

Overall Objectives

This study was designed to test the universality of the effects of the individual’s coping behaviour as driven by demographic characteristics and influences from his/her social environment to specific situations. Adjustment is by definition an overt achievement more or less discernible to other people, whereas personality is an inferred construct, even for the behaving individual, and, therefore, is less likely to be similarly appraised by various sources. Following Baron and Kenny (1986), we assume that coping styles, here represented as personality and general orientation, mediate the effects of the four major domains of predictors. By that, we mean that demographic variables, along with family, peer and cultural characteristics, influence the coping styles of the child, which in turn affect her/ his adjustment to specific situations, at school, with friends, and at home with the family.

Our overriding aim was to bring together into one study the predictors of adolescent adjustment identified in restricted research contexts by people working in various areas, in order to test their comparative strength and their combined contributions in understanding adolescent adjustment. Using our typology to structure these predictors (demographic or specific social environment), we have developed a model to drive our analyses which assumes more than one type of data, more than one source of information, more than one situation in which adjustment applies, and more than one sample. Particular attention was paid to measurement effects, by varying the wording of questions and the direction of response as much as possible. Data were solicited from more than one source, so that the conclusions could either be shown to generalize across observers or to be specific to the person doing the observing. Using the same predictors, we were able to compare their generality or specificity across situations. Finally, in gathering information from more than one sample, we could replicate the findings, as well as point to the influence of the largest social environmental network in this study, the general culture or nation on the adaptation process.

Specifically, the five objectives of the project were:

- To ascertain relations among measures of adolescent adjustment to three domains: school, friends and family; using parent, teacher and peer assessment, in addition to self-report. This assumes that the source of ratings of adjustment to a specific situation will be determined by different predictors, though there will be a positive relationship between adjustment ratings in the same domain. Outcome measures based on different raters have normally been treated as noise or error in measurement of the same underlying latent variable. Here we assume that same domain outcome variables reflect models with different antecedents. For example, though the child’s self-reported degree of satisfaction with school is associated with his/ her judgement of academic performance, it is a different aspect of the general domain of academic adjustment, as it has some different predictors (see Chapter 4, Figure 4.1).

- To test the proposed model which we imposed on our data: that the effects on adjustment in a particular situation (academic, interpersonal or family) are mediated by an overall predisposition to appropriate coping behaviour.

- This rests on our distinction between a general, overall style of adapting to the various demands of the environment and the relative success or failure of the outcome (adjustment) depending on the relationship between the demands of the situation and the coping styles of the individual. To identify predictors of adjustment from the demographic characteristics of the adolescents.

- To establish the relative importance of influences from the adolescent’s social environment, here represented by variables from the family, their classroom friends and cultural norms.

- To establish relationships within all seven samples drawn from urban youth in seven industrialized countries, as a means of understanding cross-cultural differences.

The Model

Figure 1.1 also introduces our variables into the model used in our study. These are classified as outcome variables, antecedents, and mediators. Outcomes (column 3) are adjustment to the three foci discussed above: school, friends and family, as judged by the self and others.

Mediating variables (column 2) are the three personality characteristics: self-esteem, anxiety and hostility, plus the child’s cognitive appraisal of school means study. A number of different meanings were tapped; those of particular concern here are academic and discipline on the one hand, friendship and recreation on the other. By designating these mediating variables, the implication is that the effects of all antecedent vari...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- 1 Background and Overview

- 2 The Study

- 3 Measures of Adjustment and their Personality and Demographic Correlates

- 4 Models of Adjustment: Demographic Antecedents and Personality Mediators

- 5 Measuring Family Relations

- 6 Models of Adjustment: Family Relations

- 7 Models of Adjustment: Similarity to Peers

- 8 Models of Adjustment: Cultural Impact

- 9 Summaries and Conclusions

- Appendix: Scales

- References