![]()

Section 1

Resilience as Adaptive Process to Stress and Trauma

Part A

Resilience as Biobehavioral Adaptation

![]()

Jaak Panksepp

In the context of basic mammalian adaptation, resilience refers to the intrinsically endowed capacities of an organism to manage challenges in a life-preserving manner. For humans it is the ability to maintain composure and equanimity along with creative and productive life problem solving in the face of repeated vicissitudes. Resilience refers to basic flexible life-preserving behavior patterns that are promoted by mammalian affective systems of the brain and the organism’s interaction with the environment. Fundamental brain emotional systems consisting of primary-process emotions mediate rewarding and punishing states (Panksepp, 1998, 2005; Panksepp & Biven, 2012).

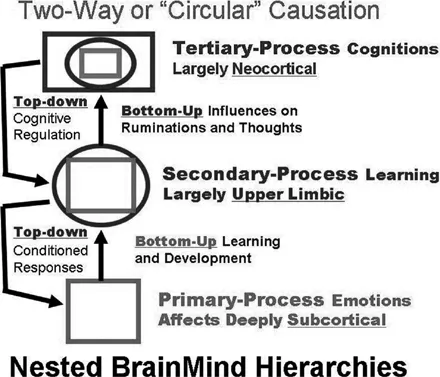

Such primal affective systems ramify widely in the brain, establishing hierarchical bottom-up controls that often dictate the more developmentally programmed top-down controls. Animal research tells us more about the bottom-up controls than human research, since we have access to deep brain mechanisms. Human research has much more to say about the top-down controls than animal brain—behavior relationships, since humans can provide direct verbal descriptors of the internal cognitive features of their minds. In sum, animal research tells us much more about the cross-mammalian affective foundations of mind, while human research is vastly more informative about higher mental abilities, many of which are truly unique to humans. But the lower subcortical mind that elaborates affective consciousness (Panksepp, 2007a) is a critical platform upon which higher human mental abilities are constructed, and is supported by the vastly expanded neocortex. This nested hierarchical view is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

This nested hierarchical arrangement consists of the intrinsic, foundational emotional systems of the brain, termed primary process. These systems not only generate instinctual forms of action readiness (Darwin, 1872; Panksepp, 1982) but are also experienced as primal affective states (Panksepp, 1998, 2005). Higher cognitive elaborations, or tertiary processes, are linked to emotional feelings, the feelings that intrinsically guide not only behavioral choices but patterns of thinking and cognitive styles that lead to top-down controls. The bridge between the primary-process feelings and higher cognition is the vast intermediate layer or secondary-process brain functions that control learning and memory. Secondary process arises from and represents deeply unconscious processes of the brain. This intermediate bridge allows the affective states to interface effectively with the environment and to provide knowledge for the higher mental apparatus to generate complex perceptions, thoughts, and ideas of human cognitive consciousness. This higher-order tertiary mind stuff is almost impenetrable in animal research subjects, especially since most of it is learned developmentally and culturally through vast plastic potentials of our expanded cortex.

My focus will be largely on the foundational layer of the BrainMind,1 critical for affective consciousness. It has received the least attention in neuroscientific and psychological

Figure 1.1 Nested hierarchical structure of primary, secondary, and tertiary affective processes. The figure illustrates how nested hierarchies are integrating lower brain functions into higher brain functions that exert top-down regulatory control of behavior at mature development. Adapted from Northoff, Wiebking, Feinberg, & Panksepp (2011).

studies of the human mind. The interactions of these distinct types of consciousness—affective and cognitive—can be described as state-and-channel functions of the brain (Panksepp, 2003). Their interactions are not well understood, but we can be confident that the emotional-affective mind is evolutionarily very ancient and homologous (genetically similar) in all mammals. The cognitive layer is more recent and is capable of diverse cognitive learning about oneself and the world. Determining how these levels of mind can be integrated will be a challenge and a great opportunity for 21st-century psychology and neuroscience as well as the topic covered here—the interrelations of mental health and resilience.

The reason that affective forms are best understood neuroscientifically through brain—behavior studies of other animals, while cognitive forms are much easier to study in humans, is simple. We can directly manipulate and monitor the subcortical affective/emotional activities in animals, since those evoked states are clearly rewarding and punishing; in humans, such work cannot be conducted. Animal research opens a window into human emotional primes and their mammalian neuro-evolution that can be explored empirically. My guiding premise will be that adaptive strengths and weaknesses of mammalian functions will be manifested dramatically in the construction of the higher cognitive mental apparatus of humans (Solms & Panksepp, 2012), one that promotes sustainable positive affect, optimism, and resilience as well as establishes chronic negative affect and pessimism. Cognitive functions surely contribute to the emergence of affects, but their affectively desirable and troublesome features originate in the ancient psychological processes that arise from below the neocortex.

The social resilience of animals and humans depends heavily not only on the intrinsic (genetic) strengths and weaknesses of the primary-process emotional level, but also on how well these plastic systems have been molded by learning and the developmental/epigenetic changes that result from the world in which organisms find themselves. In this chapter, I will focus mainly on one psychiatric condition, depression, while concurrently highlighting how early developmental joyful play experiences can modify an individual’s capacity for future affective-resilience adaptations. A key position is that we can discover new therapeutic approaches through our biological understanding of the brain substrates of specific emotions. Finally, preclinical animal models can promote a foundational understanding of human positive and negative socio-affective systems that can be shifted toward more adaptive resilient paths through epigenetic molding of the primary-process affective networks as well as via individual learning. These can promote the construction of the higher mental abilities along either enthusiastic-sanguine trajectories or negativistic-cynical ones (see a recent overview in Narvaez, Panksepp, Schore, & Gleason, 2012).

THE PRIMARY-PROCESS EMOTIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE MIND

Abundant preclinical investigations with animal models in the field of affective neuroscience have now illuminated various primary-process genetically provided emotional networks of the brains of all mammals that have been studied. The largest amounts of data have come from laboratory rats, which are remarkably playful, prosocial animals and, as omnivorous opportunists, have existed alongside humans throughout history. All evolutionarily dedicated circuits for basic emotional systems are subcortically concentrated (see Panksepp & Biven, 2012 for the most recent summaries), leaving abundant room—a vast blank slate—for social constructions and elaboration in the higher reaches of the human brain, especially the neocortex (Panksepp, 2007a). Indeed, since the needed neuroscientific understanding cannot ethically be harvested from human research, animal work is critical for achieving progress in certain psychological areas of ultimate human concern: How do affective feelings arise from neural activities? Modern brain imaging can highlight many interesting correlates and higher brain regions of interest, but it can tell us little about the details of the subcortical primes. The lower brain is so interwoven with diverse positive and negative affective systems that fMRI is often only effective in discriminating distinct affects at the nerve terminal regions of such systems, such as the nucleus accumbens for the SEEKING2 system (Knutson & Greer, 2008) or the amygdala and associated circuits within the “limbic lobe” for FEAR (Heimer & Van Hosen, 2006; Panksepp, Fuchs, & Iacabucci, 2011).

The emotional primes are coherent unconditioned action systems of the mammalian brain. At a minimum, they consist of the following seven networks: SEEKING, RAGE, FEAR, sexual LUST, maternal CARE, separation-distress PANIC/GRIEF (henceforth PANIC), and joyful PLAY. The capitalization serves to distinguish primary-process affective networks common to all mammals from vernacular terms, such as interest, anger, or anxiety, and their particular cognitive manifestations arising from interactions with the world. The emotional primes were identified with deep brain stimulation (DBS). The critical, replicable fact is that, wherever in the brain one can evoke distinct and coherent emotional responses with DBS, one can routinely demonstrate that those brain-state shifts always can be used as “rewards” and “punishments” in simple approach/anticipation and escape/punishment learning tasks (Panksepp, 2011).

THE FUNCTIONS OF EMOTIONAL PRIMES

These affective networks are “survival circuits” that regulate life processes. Affects exist because they promptly indicate whether animals are on the paths of increased or decreased survival. Affects intrinsically anticipate the future, and they are major guides in the genesis of learning through neuropsychological “laws of affect” that have remained elusive. For instance, although the mammalian brain may not have any evolutionarily dedicated “social-attachment system,” it does have various affective-emotional circuits that rapidly mediate attachments through social-emotional learning. PANIC arousal in young animals is indexed by characteristic isolation calls as animals experience social isolation distress, a state that initially activates a vigorous general purpose SEEKING response to re-establish social reunion. If that fails, animals become inactive, in a sickly way that resembles depression. In contrast, social reunions are experienced positively—through secure and confident positive social feelings created, in substantial part, by release of brain opioids and oxytocin (Panksepp, 1981, 1992). Such rewarding states, aroused by reunion with caretakers, are the affective “glue” that helps constitute specific social attachments and attunements. As noted, such emergent secondary-process learning results from various primary-process neuroaffective dynamics mediated by rewarding neurochemistries such as endogenous opioids and oxytocin (Nelson & Panksepp, 1998). If re-attachment succeeds consistently, reinforcing independence, resilience is promoted. To the extent that it fails, animals succumb to chronically clingy and depressive affect, as John Bowlby (1980) well recognized in humans.

Because of social-ecological proximities, such rewarding states typically link youngsters to their primary caretakers, whose nurturant CARE networks are designed to promote sustained positive affective social and physical warmth, touch, and sustaining feeding activities. To the extent that nurturant CARE is provided consistently, maturation is enriched by secure social attachments that form the foundation of mammalian resilience. This provides youngsters with a “secure base” as they mature, promoting rich and developmentally diverse social dynamics that ultimately promote positive PLAY engagements, which help cement friendships, creating cohesively supportive social structures, and the living environmental supports for optimal resilience. This is true for both humans and rats. Animals that have had abundant play during early development, which can partly be fulfilled by human tickling, are more psychologically robust as they mature (Cloutier, Panksepp, & Newberry, 2012; Panksepp, 2008). To the extent that such processes do not proceed well throughout development, the incidence of mental disorders, especially depression, is increased (reviewed in Watt & Panksepp, 2009; Panksepp & Watt, 2011). This level of understanding is especially important for the goal of developing new therapies that generate positive affect and promote resilience. The accrued knowledge already has important implications for understanding the fundamental social-emotional nature of both animals and humans and the role of primal emotionality in mental development and the genesis of affective disorders.

DIMINISHED RESILIENCE AND THE GENESIS OF DEPRESSION

I will now expand on this neuroscientific version of the emergence of depression. Sustained overactivity of the separation-distress PANIC/GRIEF system is only one-half of the equation. It is one gateway to the psychic pain and increasing of depression. Another major part of this equation arises from diminished SEEKING, which reflects a downward affective spiral that arises from the diminished desire to engage with the world. This reflects a weakening of the most widely expressed basic positive affective emotional network of the brain, whose substrates at the primary-process level we have called the SEEKING system. Other investigators called it the “the Brain Reward System” (e.g., Haber & Knutson, 2010), or “wanting” (Berridge, Robinson, & Aldridge, 2009), which is a good secondary-process term, or “reward prediction error” (Schultz & Dickinson, 2000), which is a reasonable cognitive-computational tertiary-process concept...