eBook - ePub

Working to Learn

Transforming Learning in the Workplace

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The workplace is an important site for learning in today's society. This book examines the changing nature of the work and effect that this has on the skill and knowledge requirements of individuals, its implications for employment, and ways in which these changing requirements can be met.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Working to Learn by Karen Evans,Phil Hodkinson,Lorna Unwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The significance of workplace learning for

a ‘learning society’

Karen Evans and Helen Rainbird

For most people the workplace is the site of tertiary socialization, after the family and the education system. It is here that workers learn to modify their performance and to understand their roles, including their gender roles, in the structures and interactions of the organization. In this respect, job roles, position within a hierarchy and inclusion or exclusion from career ladders contribute to people’s expectations of their own and others’ potential to learn. Workplace learning is of central importance and a crucially important site for learning, whatever vision is held of a learning society. At the same time, workplace learning is poorly understood and under-researched, but has moved to centre stage in discourses about the socalled ‘knowledge-based economy’ and in policies based on that concept.

There are different versions and different understandings of what a ‘learning society’ is and could be. For the purposes of this chapter, we adopt that of the ESRC’s programme of research on the learning society, as the most generous and inclusive we know. In this version, all citizens would:

acquire a high quality general education, appropriate vocational training and a job (or series of jobs) worthy of a human being while continuing to participate in education and training throughout their lives. A learning society would combine excellence with equity and would equip all its citizens with the knowledge, understanding and skills to ensure national economic prosperity and much more besides. The attraction of the term ‘the learning society’ lies in the implicit promise not only of economic development but of regeneration of our whole public sphere. Citizens of a learning society would, by means of their continuing education and training, be able to engage in critical dialogue and action to improve the quality of life for the whole community and to ensure social integration as well as economic success. (Coffield, 1997:450)

This chapter addresses two sets of issues that run throughout and underpin the contributions to this volume and are themselves interconnected. The first is the need to rethink what counts as learning and knowledge in relation to the workplace as a site of learning. This will allow us to arrive at a better understanding of them in the knowledge-based economy, and to do this in a way that moves beyond the dualisms which divide and fragment the field. The second set of issues concerns the balance of responsibilities and rights, in the employment relationship and in the wider society. The fact that we are talking about a learning ‘society’ means that we are talking about something more than aggregated individuals. Most of the new policies in the advanced economies such as the UK, the USA and parts of Europe have become increasingly focused on individual responsibilities with little attention paid to reciprocal rights or the social and collective dimensions of society as it relates to the workplace and the role of work in people’s lives (see, for example, DfEE, 1998). Other European partners have taken different perspectives, and the French experience (discussed in Chapter 12) illustrates how these are carried through in policy and practice. Both clusters of issues require us to make new kinds of connections while recognizing the barriers and incentives that operate.

Mapping the field of workplace learning

Our focus is on the workplace as a site of access to learning or, as the Workplace Learning Task Group defined it, ‘that learning which derives its purpose from the context of employment’ (Sutherland, 1998:5). This does not mean training, which is narrowly focused on the immediate task and restricted to business needs, but learning, which addresses the needs of a variety of stakeholders: employees, potential employees, employers and government. The distinction between training and learning is significant. The Task Group’s definition included ‘learning in, for and through the workplace’ (1998). It therefore includes a range of formal and informal learning; learning which is directed to organizational as well as employees’ needs; and learning which is accessed through the workplace. This definition is important because, in the UK at least, the workplace has become a site for ‘initiatives’, which means it becomes embroiled in acronyms and it is easy to lose sight of the heart of the central issue in the various ‘schemes’ that are either being hatched or re-branded.

Four broad but overlapping forms of learning involve workplace learning as a central feature:

- Initial work-based learning, in traineeships and apprenticeships.

- Work-based degrees and ‘foundation’ degrees.

- Non-formal work-based learning.

- Access to continuing non-formal learning opportunities through the workplace.

Group A encompasses various types of apprenticeships and traineeships undertaken by young people end-on to compulsory education. In the UK the various schemes and programmes that have evolved over the past two decades are involved in an ongoing process of re-branding.

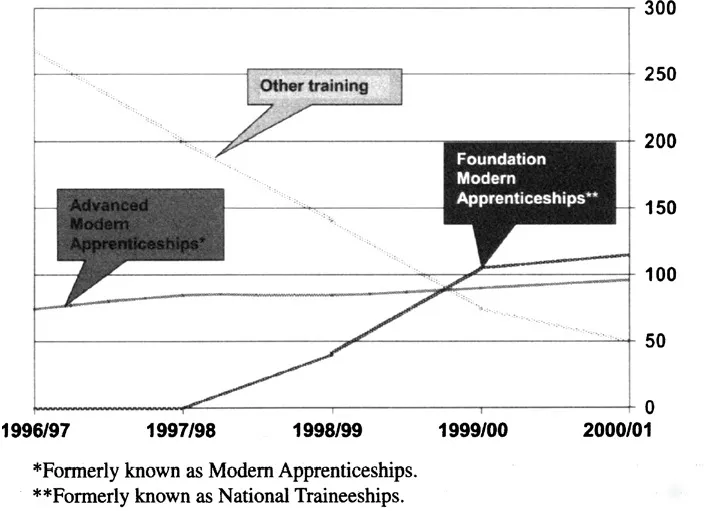

Figure 1.1 shows that the numbers of young people involved in workbased programmes levelled out overall as foundation modern apprenticeships took over from previous ‘traineeships’ and the higher level programmes became re-branded as ‘advanced modern apprenticeships’.

Figure 1.1Trends in numbers following traineeships and apprenticeships in Britain

These programmes have their parallels in most advanced economies, the differences being in how central they are to the wider systems of education and training. Apprenticeship is central to the German system, and sets the ‘rules of the game’ for all other forms of work-related education and training. In the USA, by contrast, apprenticeship is peripheral to full-time collegebased routes into the labour market.

Programmes in the second group (B) are on the increase in higher education, particularly in the USA, Australia and the UK (Boud and Solomon, 2001). In these programmes, the work experiences and achievements of ‘clients’ are given credits towards the award of degree, according to the system of assessment and regulation of the degree awarding body. Corporate clients are important users of these programmes.

In the USA, the two-year associate degree achieved a high take-up among people already in employment. Its recent counterpart in the UK, the Foundation Degree initiative, has had a slow start although work-based versions of the degree are seen as having particular potential for expansion. Developments in Group A and Group B in the UK are being seen by government as instruments for meeting the official target of a 50 per cent participation rate of younger adults in higher education by 2010. It has become clear that the target is not likely to be achievable through the fulltime education route.

Non-formal learning (C) is a dimension of initial vocational education and training and work-based degrees. It is also an important area in its own right (Coffield, 2000a; 2000b). In the UK, National Vocational Qualifications were introduced to recognize and accredit competence developed through experience and practice in work environments. But much of the most significant workplace learning never comes within the scope of qualification—it is part of mastery of the job, work roles and understanding of the work environment. Non-formal learning is defined for our purposes here as embracing learning through work and community experience, but may also include planned and explicit approaches to learning carried out in any of these environments, where these are not part of the formal education systems.

In the final group (D), where non-formal learning opportunities are made available in the workplace through external providers, the role of online learning has assumed a particular importance. The UK has provided two examples of government schemes aimed at specifically supporting lifelong learning undertaken on the initiative of the individual. These are Individual Learning Accounts (ILAs) and the University for Industry (UfI), which has been translated into ‘LearnDirect’. These are discussed further in Chapter 12. Although there is less support for collective initiative, trade unions have become advocates of lifelong learning in the workplace as part of the ‘new bargaining agenda’ (Storey et al, 1993). An exception has been the DfEE/DfES Union Learning Fund, which has supported a range of trade union initiatives on learning (see Cutter, 2000, for an evaluation).

Tensions in workplace learning

The workplace has enormous potential as a site of learning, though this is rarely fully realized. The Fryer Report (1997) argues that ‘for many (people) the workplace is the only place where they will engage in formal learning’. It is also affords many informal learning opportunities which result from interactions in workgroups and from the structure of the work environment. The discourses of Human Resource Management (HRM), the ‘learning organization’ and ‘knowledge management’ would seem to suggest that learning is a central concern in the workplace. Yet the harsh THE SIGNIFICANCE OF WORKPLACE LEARNING 11 reality of the operating environments of many public and private sector organizations means that the rhetoric is not even an aspiration, let alone a reflection of practice. Indeed, research evidence suggests that there are significant organizational and cultural barriers to the promotion of individual and organizational learning, which are all too prevalent in the UK. These include:

- cost-based competition;

- standardized products and services;

- a heavy reliance on economy-of-scale advantages, low trust relationships and hierarchical management structures;

- people management systems that emphasize command, control and surveillance, and an underlying belief that (whatever the rhetoric) people are a cost or a disposable factor of production;

- little slack or space for creativity, and a culture of blame for where mistakes (particularly those of lower-status workers) are punished. (Keep and Rainbird, 2000:190)

The relatively low levels of investment of British employers in workforce development compared to their economic competitors are well known and many factors contribute towards this. The nature of financial markets, competitive strategy, organizational structures and labour market deregulation have all been identified as contributing to an environment in which there are disincentives to employers to invest in workforce development.

Company structure may itself affect the usefulness of having a central training function. In any large organization, tensions are inevitable between the professional entrepreneurs within business units and specialist corporate functions, and this affects the advantages, if any, of a central training function and organization-wide training activities. Carey (2000) identifies three types of structure found in large companies. These are strategic planning companies, with a small number of related businesses; strategic control companies, with diversified businesses with common strategic characteristics; and financial control companies, which are owned rather than managed centrally. She argues that strategic planning companies have characteristics that contribute to the integration of training within an HRM model. In contrast, strategic control structures inhibit central coordination and the development of training standards, while financial control structures positively discourage lateral integration (p 23).

Even where organizations are fully committed at corporate level to investing in the training and development of their employees, structural factors may undermine their capacity to put these policies into practice.

Within organizations, investment is hampered by:

- the weak role of training and development within corporate structures;

- the absence of a ‘champion’ at board level;

- the tendency for training and development to be seen as an operational rather than a strategic issue;

- conflicts between corporate Human Resource strategy and operational management contribute to the difficulties of operationalizing workforce learning strategies. (Rainbird, 2000)

At the level of the workplace, this is compounded by issues relating to the management, socialization and control of the workforce. Performance management systems provide organizations with a tool for aligning individual performance with organizational objectives. Managers’ performance is assessed (and rewarded) on the basis of a short timescale and this is at odds with the longer-term nature of training and development strategies (Hansen, 2000). Product market strategies focused on price competition rather than producing quality goods for niche markets are unlikely to result in a concern for the long-term development and adaptability of the workforce. Rather, jobs are likely to be designed to involve a limited range of tasks and discretion. Consequently, the focus of intervention (or non-intervention) is more likely to reduce employees’ expectations of training and development.

Individuals are located within occupational hierarchies that provide differential access to formal learning opportunities and in jobs that provide differential access to informal learning opportunities and career progression. There is a substantial body of survey evidence which suggests that welleducated workers in professional roles are more likely to receive employerprovided training than those in routine and manual jobs on the lowest salary grades (see Ashton et al, 1999; Cully et al, 1999). As a result, some workers enter employment with expectations of access to learning and career progression and will find opportunities to learn informally in the work environment. Others will enter jobs with few opportunities for learning and progression, and low aspirations for themselves, which are reinforced by the low expectations of their managers. Their jobs may be narrowly constructed, and the pace of work, staffing levels and physical isolation may restrict opportunities for informal learning. Decisions made about training and development are not neutral: the context of workplace politics is significant to workers’ and managers’ perceptions of it. It may be regarded as a reward, giving status where there was previously little; it may serve as recognition for effort and a signal of value to the organization; and it may indicate suitability for promotion. Equally, it may be perceived as a threat, an indicator of poor performance or a signal that work is about to be intensified (Rainbird et al, 1999).

Therefore any attempt to enhance incentives (and minimize disincentives) to workplace learning has to recognize that it is not sufficient to identify forms of effective learning. They must be located in the structures and contexts that support them. Forms of learning which work effectively in one context may not be transferable to others where they are undermined by other aspects of the employment relationship, for example, job insecurity, work intensification and absence of employee voice.

The search for ways of raising workers’ skill levels through workplace learning interventions has first to grapple with the problem of identifying the complexity of learning in work settings, particularly the sources of informal learning. Ways of talking about and conceptualizing workplace learning need to be found. A second step is to investigate what counts as effective learning in workplaces, from the perspectives of the learners themselves, their employers and other interested parties such as trade unions, training organizations and government agencies. In addition to the range of learning activities within and around the job, it is important to establish how learning is perceived and experienced. This is affected, in particular, by the questions,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Editors’ introduction

- Chapter 1: The significance of workplace learning for: a ‘learning society’

- Chapter 2: Learning careers: conceptualizing lifelong work-based learning

- Chapter 3: Contrasting approaches to the role of qualifications in the promotion of lifelong learning

- Chapter 4: The interaction between qualifications and work-based learning

- Chapter 5: The challenges of ‘making learning visible’: problems and issues in recognizing tacit skills and key competences

- Chapter 6: Developing pedagogies for the contemporary workplace

- Chapter 7: An approach to learning at, for and through the workplace: a trade union case study

- Chapter 8: Education and training for small and medium-sized enterprises

- Chapter 9: The dynamics of workplace learning: the role of work organizations

- Chapter 10: Putting skills in their place: the regional pattern of work skills in Britain

- Chapter 11: Policy interventions for a vibrant workbased route—or when policy hits reality’s fan (again)

- Chapter 12: No rights, just responsibilities: individual demand for continuing training1

- Chapter 13: Six challenges for the future

- Appendix: Economic and Social Research Council Teaching and Learning Research Programme