![]()

1

Reading the past

What is architectural history?

Architectural History is more than just the study of buildings. Architecture of the past and the present remains an essential emblem of a distinctive social system and set of cultural values, and as a result it has been the subject of study of a variety of disciplines. But what is architectural history and how should we read it? This book examines both the role of architecture in the construction of its histories and, equally, the way in which histories of architecture are written – in other words how the forces of history impact on our perception and understanding of the architecture of the past. But first what is meant by architecture? And what is history?

History

Let's begin by unpacking the term ‘history’. History is about the past. Yet it exists only in the present – the moment of its creation as history provides us with a narrative constructed after the events with which it is concerned. The narrative must then relate to the moment of its creation as much as its historical subject. History presents an historian with the task of producing a dialogue between the past and the present. But as these temporal co-ordinates cannot be fixed, history becomes a continuous interaction between the historian and the past. As such, history can be seen as a process of evaluation whereby the past is always coloured by the intellectual fashions and philosophical concerns of the present. This shifting perspective on the past is matched by the fluid status of the past itself. In this way structuralist and post-structuralist1 discourse has fundamentally altered our view and understanding of knowledge and history. The preoccupation with the nature of history and historical truth is scrutinized in terms of its linguistic and textual possibilities. Similarly, such thoughts and questions as ‘What is history?’ were voiced by historians in the 1960s as part of a discourse around the discipline. Historians were beginning to question what they were doing and the philosophical implications of their construction of the discipline. In this way we see that the concern with what history is is not merely the preoccupation of social and cultural theorists intent on dismantling traditional canons of thought, it is a fundamental core of the historiography of history.

One of the principal concerns when considering of the nature of history is the question of subjectivity. Now that human knowledge is no longer viewed as being a stable and immutable – a kind of humanistic or enlightenment vision of the subject knowing both the world and itself – we define subjectivity as a state of flux and change. History, as a part of human knowledge, cannot then be seen as a solid ever-expanding discourse developing along generally accepted trajectories. We have dissembled these certainties in order to question established principles of knowledge upon which historical thought is based.

The recognition of the role and importance of subjectivity in the construction of histories does, by implication, negate the possibility for objectivity in the writing of history. But there will always be historical narrative and, consequently, a narrative voice, be it hidden in the syntactical structure of the writing by, for instance, the absence of first person or the use of simple past tense. But this is a sleight of hand which gives the reader a sense of immediate contact with the past without the presence of an interlocutor. This apparently ‘unmediated’ contact gives history a kind of privileged status of objective knowledge.

Narrative and its role in history is the concern of Roland Barthes’ influential essay on Historical Discourse

What really happens is that the author discards the human persona but replaces it by an ‘objective’ one; the authorial subject is as evident as ever, but it has become an objective subject . . . At the level of discourse objectivity, or the absence of any clues to the narrator, turns out to be particular form of fiction, where the historian tries to give the impression that the referent is speaking for itself.2

Here we see how the theoretical preoccupations with language and textuality enable us to examine the kinds of narrative constructions used in the telling of histories and the consequences these different modes of narrative have on the subject. Historical reality is then a ‘referential illusion’, in which we try to grasp the reality (the referent of language) that we believe lies beyond the barrier of the linguistic construction of its narratives. In this way history becomes a Myth or an ideology as it purports to be reality. Indeed, storytelling is often seen as one of the most important functions of writing histories and fundamental to the nature of the discipline. A story requires a beginning, middle and end, based on a series of events that take place over a period of time. Lawrence Stone sums up this understanding of narrative:

Narrative is taken to mean the organization of material in a chronologically sequential order and the focussing of the content into a single coherent story, albeit with sub-plots. The two essential ways in which narrative history differs from structural history is that its arrangement is descriptive rather than analytical and that its central focus is on man not circumstances. It therefore deals with the peculiar and the specific, rather than the collective and statistical. Narrative is a mode of historical writing, but it is a mode which also affects and is affected by content and method.3

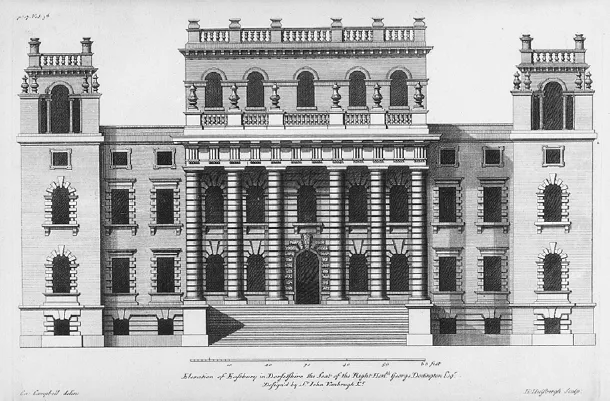

Coherence is then an essential part of narrative in order for it to work as a story and for it to work in Barthes’ terms as a myth or reality. This coherence or linearity is a selective process that requires the exclusion of material and the imposition of a unity on a disparate set of historical events or circumstances. This consequence of the desire for narrative relates to the empirical tradition; it is one way of ordering facts – ‘letting them speak for themselves’ – and has a built-in notion of progress. Two orders of narrative used frequently in architectural history are the narrative of style and the narrative of the author (architect). The narrative of style allows the ordering of architectural production, whether anonymous or not, through aesthetic categories. Here the heterogeneity, discordance and lack of synchronization between different strands of architectural production can be unified into what Laura Mulvey has called ‘parabolic patterns of narrative’,4 with elements/movements coming into ascendancy and then declining. This provides a dominant narrative thrust in history within which the ideas of progress movement and development are expressed through a narrative of opposition and polarisation. This is evident in stylistic histories where teleological patterns of stylistic dominance and recession are imposed. In this way English Palladianism, typified by Inigo Jones (Figure 1.1), is followed by English Baroque, typified by Sir John Vanbrugh (Figure 1.2) is followed by English Palladianism, typified by Lord Burlington (Figure 1.3). Vanbrugh rejected the style of Jones in the same way that Burlington rejected the style of Vanbrugh. But what of the substance of these narratives – the factual information?

Figure 1.1 The Banqueting House, Whitehall, London by Inigo Jones, c. 1622 (photo, author).

The choice of narrative is an important way of making the facts speak. But this was rarely recognised by nineteenth-century historians, many of whom were oblivious to the nature and consequences of the narrative choices available to them. They believed, instead, that at some point all facts would be known and thus to provide an archival truth. There are traces of this today where narrative choices, centred for instance on biography, style or social history, stem from the belief that an empirical reiteration of the facts presents reality. The adoption of ‘scientific’ techniques of narration from the early nineteenth century onwards, where the historian dissociated himself (usually) from literature in favour of science, reinforces the primacy of factual accuracy and empirical information and the myth of truthful reality.

Wilhelm von Humboldt's essay entitled The Historian's Task, written in 1821, leaves us in no doubt as to the prevalent view:

The historian's task is to present what actually happened. The more purely and completely he [note ‘he’] achieves this, the more perfectly has he solved this problem. A simple presentation is at the same time the primary indispensable condition of his work and the highest achievement he will be able to attain. Regarded in this way, he seems to be merely receptive and productive, not active and creative.

Figure 1.2 Eastbury, Dorset by Sir John Vanbrugh, illustrated in Vitruvius Britannicus, Volume III, plate 17, 1725 (private collection).

Facts are the substance of this ‘objective’ historical narrative. But what are they? And what is the relationship of the historian to the facts? Is it the duty of the historian, as Ranke amongst others suggests, to let the facts speak for themselves? But the facts history purports to describe are in the past – no longer accessible to direct inspection or empirical observation. They are untestable and have no yardstick of known reality to which they can be compared.

Again, this was a concern of historians before the post-structuralist discourses began to permeate historical thinking. W H Walsh in his Introduction to the Philosophy of History considered the question of truth and fact in history, which he saw as relating to the more general theory of knowledge.

We are apt to suppose that the facts in any branch of meaning must be in some way open to direct inspection, and that the statements of experts in each branch can be tested by their conformity with them . . .

The most striking thing about history is that the facts it purports to describe are past facts; and past facts are no longer accessible to direct inspection. We cannot, in a word, test the accuracy of historical statements by simply seeing whether they correspond to a reality which is independently known. How then can we test them? . . .

. . . we do so by referring to historical evidence. Although the past is not accessible to direct inspection it has left ample traces of itself in the present, in the shape of documents, buildings, coins, institutions, procedures and so forth.5

Figure 1.3 Chiswick House, London by Lord Burlington, c. 1725 (photo, author).

Every assertion must be based, therefore, on some kind of evidence. If there is no evidence history, according to Walsh, becomes an inspired guess or a fiction. But the original sources need scrutiny and the historian has to decide whether or not to believe them; they are not the ‘ultimate datum to which we can refer to test historical judgements’. Walsh places historical thinking firmly in the present so that the historical truth arrived at by the historian is a product of the present and not the past.

The past does leave traces of itself in the present in the form of archives, whether they be documents, institutions or indeed buildings. This archive of knowledge about the past, no matter how incomplete, allows the historian to present an argument or reconstruction based on this body of ‘evidence’ or facts. But the ‘facts of history can never come to us in a pure state’, as the historian E H Carr observed: ‘they are always refracted through the mind of the recorder’.6 So we not only have an imperfect and uncorroborated archive, but we also have the subjectivity of the historian. Indeed, Carr advises that ‘It follows that when we take up a work of history, our first concern should be not with the facts which it contains but with the historian who wrote it.’7

Architectural historians and their histories of architecture are the substance of this enquiry. The dialogue between the historian and his/her facts is an essential element Michel de Certeau calls it ‘the particularity of place where discourse is produced’. He argues that this

. . . [puts] the subject-producer of knowledge into question . . . One can, of course, either maintain that the personal status of the author is a matter of indifference (in relation to the objectivity of his or her work) or that he or she alone authorizes or invalidates the discourse (according to whether he or she is ‘of it’ or not). But this debate requires what has been concealed by an epistemology, namely, the impact of subject-to-subject relationships (men and women, blacks and whites, etc.) on the use of apparently ‘neutral’ techniques and in the organization of discourses that are, perhaps, equally scientific. For example, from the differentiation of the sexes, must one conclude that a woman produces a different historiography from that of a man? Of course, I do not answer this question, but I do assert that this interrogation puts the place of the subject in question and requires a treatment of it unlike the epistemology that constructed the ‘truth’ of the work on the foundation of the speaker's irrelevance.8

De Certeau is particularly concerned with histories and the historiography of ‘other’, but this sensitivity to the subject-to-subject relationship outlined here has resonance with the concerns of this study. And de Certeau sees these categories of historical discourse as magnifying more general concerns about the narratives and subjects of history outlined in this chapter. At this point I would add a third party to this perceived dialogue between historian and narrative – the reader. What do we bring to and what do we want from these discourses? And what is our ‘experience’ of the past?

The past is encountered and mapped through the discovery and ordering of facts which are not static, fixed – or indeed certain. Foucault amongst many other thinkers asserts that there is no essential order, meaning or framework as knowledge is forever changing and is itself subject to periodisation or fashion, as is the discipline of history itself. These epistemes, as Foucault referred to them, were both a means of exploring and understanding the historical discourses of the past and a way of discovering and interpreting the production of the present.

If interpretation were the slow exposure of the meaning hidden in an origin, then only metaphysics could interpret the development of humanity. But if interpretation is the violent or surreptitious appropriation of a system of rules, which in itself has no essential meaning, in order to impose a direction, to bend it to a new will, to force its participation in a different game, and to subject it to secondary rules, then the development of humanity is a series of interpretations. The role of genealogy is to record its history: the history of morals, ideals, and metaphysical concepts, the history of the concept of liberty or of acetic life; as they stand for the emergence of different interpretations, they must be made to appear as events on the stage of historical process.9

History can then imply chronology and sequence, perhaps even a sense of development and progress. Linearity is not necessarily problematic – it is only one route through knowledge – but if we accept that architecture and urban environments are complex entities with interwoven meanings, this straightening out of the different strands or chains of facts/events can both clarify and obscure our readings of these phenomena.

Architecture

‘Architecture’ may at first appear to be a more fixed and finite term. It has a threedimensional, tangible, useable form. But questions remain about what can be considered architecture and what cannot, and by this I mean that we usually understand architecture to incorporate aesthetic as well as functional consideration into its structure. Anything that does not fall into this category can be described as ‘just a building’. This may seem too simple. Can architecture be determined solely by the use of refined architectural style – high or polite architecture instead of vernacular? This view reduces architecture to an aesthetic – a cosmetic transformation or intervention of which the cultural and historical meaning remains in the realms of the visual. But style has been an essential tool in the construction of the narratives of architectural history. If we then consider the function of a building, is the answer really as simple as Sir Nikolaus Pevsner's view that ‘a bicycle shed is a building: Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture’?10 In one way we return to the importance of the aesthetic, whilst at the same time imposing hierarchies of utility. Moreover, can we deny that technical and structural innovations play a crucial part in the design process – both in terms of infrastructure and formal possibilities. At what point does this become ‘architecture’? The complexities revealed by these questions amplify when buildings ...