- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This second edition of Geographic Information Systems builds on the strengths of the first, and incorporates important recent advances in GIS development and major new socioeconomic datasets including new census data. Martin presents an accessible introduction to the history, principles and techniques of GIS, with a unique focus on socioeconomic applications. This non-technical volume addresses the needs of students and professionals who must understand and use GIS for the first time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geographic Information Systems by David Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

This book is intended to provide a general introduction to the field of geographic information systems (GIS). More specifically, it is aimed at those who have a particular interest in the socioeconomic environment. In the following chapters, the reader will find an explanation of GIS technology, its theory and its applications, which makes specific reference to data on populations and their characteristics. The aim is not to provide detailed analysis of fields such as database management systems or computer graphics, which may be found elsewhere, but to introduce GIS within a strong framework of socioeconomic applications. As will be seen, many early GIS applications related primarily to the physical environment, both natural and built. Much writing on the subject reflects these themes, and is unhelpful to the geographer or planner whose interest lies in the growing use of GIS for population-related information. The unique issues raised by these new developments form the specific focus of this text. This introduction sets the scene, both in terms of GIS and of the socioeconomic environment. Some concepts appearing here with which the reader may be unfamiliar will be addressed in more detail as they are encountered in the text.

Geographic Information Systems

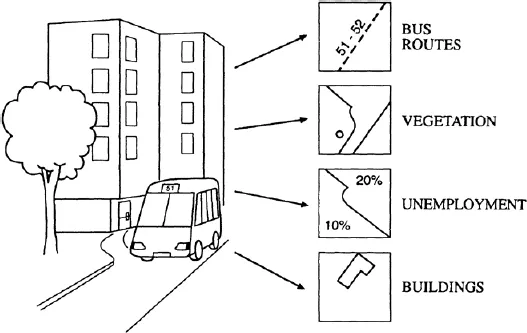

Geographic information, in its simplest form, is information which relates to specific locations. Figure 1.1 illustrates four different types of geographic information relating to a typical urban scene. The physical environment is represented by information about vegetation and buildings. In addition, there are aspects of the socioeconomic environment, such as bus service provision and unemployment, which cannot be observed directly, but which are also truly ‘geographic’ in nature. The 1980s saw a massive rise in interest in the handling of this information by computer, leading to the rapid evolution of systems which have become known as ‘GIS’. It must be stressed, however, that the use of digital data to represent geographic patterns is not new, and only in the last decade has ‘GIS’ become a commonly used term. Nevertheless, confusion exists as to what exactly constitutes a GIS, and what functions it should perform. While the commercial world is able to offer systems with ever-increasing functionality, there are still no generally accepted theoretical guidelines for their application. Certainly, there has been no clear theoretical structure guiding the developments which have taken place, largely in response to specific user needs. This lack of theoretical work has been a common criticism in much writing about the field (Berry, 1987; Goodchild, 1992).

Figure 1.1 Examples of geographic information

The systems which we now call ‘GIS’ have grown out of a number of other technologies and a variety of application fields, and are thus a meeting point between many different disciplines concerned with the geographic location of their objects of study. GIS potentially offer far greater power for manipulation and analysis of data than had been available with earlier systems, broadly aimed at map or image reproduction, but also place greater demands on data accuracy and availability. The data in GIS may be accessed to obtain answers to questions such as ‘what is at location X?’, ‘what areas are adjacent to route R?’ or ‘how many of object A fall within area B?’, which is true geographic ‘information’. A major theme which will run through these discussions is the way in which GIS provide an accessible and realistic model of what exists in the real world, allowing these kinds of questions to be addressed. This is very much more than merely using a computer to ‘draw maps’, and is potentially a very powerful tool, but it also provokes questions as to the nature of the ‘real’ world, and forces us to consider whose definitions of ‘reality’ we are going to adopt. The implications of these developments for geography are far-reaching, as they offer a technology which can dynamically model some aspects of the geographic world. The need to examine carefully the mechanisms by which this is achieved is therefore fundamental. A geographic information system, then, according to these criteria, may be summarized as having the following characteristics:

- Geographic: The system is concerned with data relating to geographic scales of measurement, and which are referenced by some coordinate system to locations on the surface of the earth. Other types of information system may contain details about location, but here spatial objects and their locations are the very building blocks of the system.

- Information: It is possible to use the system to ask questions of the geographic database, obtaining information about the geographic world. This represents the extraction of specific and meaningful information from a diverse collection of data, and is only possible because of the way in which the data are organized into a ‘model’ of the real world.

- System: This is the environment which allows data to be managed and questions to be posed. In the most general sense, a GIS need not be automated (a non-automated example would be a traditional map library), but should be an integrated set of procedures for the input, storage, manipulation and output of geographic information. Such a system is most readily achieved by automated means, and our concern here will be specifically with automated systems.

As suggested by this last point, the data in a GIS are subject to a series of transformations and may often be extracted or manipulated in a very different form to that in which they were collected and entered. This idea of a GIS as a tool for transforming spatial data is consistent with a traditional view of cartography, and will be used here to help structure the discussion of the concepts of GIS.

A brief review of the diverse academic and commercial literature would suggest that typical application areas have been land resources and utility management, but applications in the fields of census mapping and socioeconomic modelling have experienced massive growth following the new censuses of the early 1990s, and there has been a corresponding increase in large in-house databases compiled by many organizations. The absence of any firm theoretical basis means that we have no mechanisms for evaluating the appropriateness of these diverse applications. This is of particular importance in the context of growing interest in the field, as the existing theoretical work is broadly descriptive, and cannot offer much help in any specific application. Evaluation of GIS installations has been largely in terms of the financial costs and benefits of replacing traditional procedures. The breadth of potential applications has made GIS a subject of government and research council interest in the UK and USA and there is currently much demand for training in the use of these systems. In 1987, the Committee of Enquiry into the Handling of Geographic Information in Britain published its influential report, commonly referred to as the ‘Chorley Report’ (Department of the Environment, 1987). This report touched on many of the issues which will be raised here, particularly illustrating the importance of spatially referenced socioeconomic information.

In drawing together submissions for its investigations, the Chorley Committee also demonstrated the difficulties faced by those wishing to obtain clear information about GIS, because of the diverse applications and piecemeal development mentioned above. Much of the relevant literature existed in the form of conference proceedings and papers in technical journals relating to specific applications. It was not until 1987 that an international academic journal concerned purely with GIS emerged. The last five years have seen an enormous explosion in the GIS literature with additional GIS-related academic journals, a number of international trade journals and many new textbooks, but the commercial nature of the industry has led to the continuance of a heavy reliance on a non-academic literature with limited availability. Available textbooks now range from large collections of papers covering all aspects of GIS (such as Maguire et al., 1991) to those concerned with very specific application areas (such as Haines-Young and Green, 1993). This diversity of literature still poses difficulties for those concerned with socioeconomic information who may have little familiarity with the earlier application fields.

References to the operation of specific software systems have been avoided here as far as possible, due to the speed with which such information dates. It is a feature of the buoyancy of GIS development that software suppliers are constantly developing new modules to handle particular aspects of specialized data processing, meet new international transfer and processing standards, or take advantage of some new range of workstation (for example), that the situation changes with each new software release. The topics chosen for discussion are felt to be sufficiently well established and enduring that they will aid the reader in understanding the important aspects of specific systems with which they may come into contact.

Socioeconomic Data

An important and fast-developing application field for GIS is that of socioeconomic or population-related data. By population-related data we are here referring to data originally relating to individual members of a population which is scattered across geographic space, such as the results of censuses and surveys and the records gathered about individuals by health authorities, local government and the service sector. These data are here contrasted with those which relate to physical objects with definite locations, such as forests, geological structures or road networks. Clearly, there are relationships between these types of phenomena, as they both exist in the same geographic space, but in terms of the data models with which we shall be concerned, it is important to recognize the distinction between them.

A number of census mapping systems with broadly GIS-type functionality and data structures have evolved. GIS are now being used extensively for health care monitoring, direct mail targeting and population mapping (Hirschfield et al., 1993; Birkin, 1995) However, data relating to dynamic human populations are very different in their geographic properties to those relating to the physical world: the location of any individual is almost always referenced via some other spatial object, such as a household address or a census data-collection unit. Unlike a road intersection or a mountain summit, we are rarely able to define the location of an individual simply by giving their map reference. This has far-reaching implications: socioeconomic phenomena such as ill health, affluence and political opinion undoubtedly vary between different localities, but we cannot precisely define the locations of the individuals which make up the chronically sick, the affluent or the politically militant. If GIS are to be used to store and manipulate such data, it is crucial that much care is given to ensuring that the data models used are an acceptable reflection of the real world phenomena. Different interest groups may have very different conceptions of which phenomena are important and what is ‘acceptable’. Again, the absence of a theoretical structure makes it difficult to identify the nature of the problems, and the levels at which they need to be addressed.

The importance of these issues in many countries is increased by a growing interest in geodemographic techniques which has been fuelled significantly as the results of the censuses of 1990 (e.g. USA, France) and 1991 (e.g. UK, Portugal) have become available, together with much more data about the individual collected by a wide range of organizations (Beaumont, 1991; Arnaud, 1993; Thrall and Elshaw Thrall, 1993). There continues to be growth in the demand for computer systems to manipulate and analyse all these new sources of information, and GIS geared specifically towards the handling of socioeconomic data are multiplying rapidly. In the light of these developments and the technology- and application-led growth of GIS to date, it is essential that a clear theoretical framework be established and that the particular issues relating to socioeconomic data types be understood. These are the issues which this book seeks to address, and we will often return to consider their implications during this introduction to GIS.

Structure of the Book

Chapters 2 and 3 are essentially historical, tracing the development of GIS through two closely allied technologies, computer-assisted cartography and image processing, and going on to consider the present role of GIS. Some introductory remarks on computers and information systems should provide the essentials for those with no computing experience, but it is assumed that the reader will look elsewhere for more detailed explanation of computers and their operation. Chapter 2 demonstrates the largely ad hoc development of GIS, and introduces the concept of the information system as a way of modelling certain aspects of the real world. This idea is central to the picture of GIS technology portrayed in later chapters. Chapter 3 places these technological developments in context by giving attention to some typical GIS applications and demonstrating the environments in which these systems have been used and developed. Particular attention is given to application examples involving socioeconomic data, and the chapter illustrates the powerful influences of computer capabilities, and physical-world applications on the evolution of contemporary systems.

Chapter 4 reviews the existing theoretical work on GIS, identifying two main themes. The first of these, the ‘components of GIS’ approach, is based around the functional modules which make up GIS software. The second theme, termed the ‘fundamental operations of GIS’ seeks to view GIS in terms of the classes of data manipulation that they are able to perform. Neither approach offers much help to those wishing to transfer GIS technology to new types of data, and an alternative framework is presented which focuses on the characteristics of the spatial phenomena to be represented and the transformations that the data undergo. These are identified as data collection, input, manipulation and output. The transformational view of data processing is consistent with current theoretical work in computer cartography (Clarke, 1990), and develops the differences between GIS and merely cartographic operations. This discussion serves to identify further the unique characteristics of socioeconomic phenomena over space. A grasp of these conceptual aspects is seen as essential for a good understanding of the ways in which GIS may be used, and the correct approach to developing new applications. A theme which runs throughout this text is the importance to socioeconomic GIS applications of having a clear conceptual view of what is to be achieved. This is in clear contrast to much of the existing work. Chapter 4 also addresses the extent to which GIS are contributing to the development of a separate ‘geographic information science’.

The four important transformation stages identified in Chapter 4 form the basis for the discussion which follows. Chapters 5 to 8 explain how GIS provide a special digital model of the world, looking at each of the data transformations in turn, and giving particular attention to data storage. In Chapter 5, data-collection and input operations are considered. This includes an overview of some of the most important sources of spatially referenced socioeconomic information, with particular reference to the way in which these data are collected and the implications for their representation within GIS. Knowledge of the processes of data collection is very important to ensure the valid manipulation of the data within GIS, and this issue is addressed. The discussion then moves on to examine the techniques for data entry into GIS, looking at vector, raster and attribute input methods. This section includes data verification, stressing the difficulties involved in obtaining an accurate encoding of the source data in digital form.

The various structures used for the organization of data within GIS form a very important aspect of their digital model of the world, and different data structures have important implications for the types of analyses which can be performed. In addition to the common division into vector and raster strategies, object-oriented approaches and triangulated irregular networks are considered. There are a variety of approaches to the encoding and storage of information, even within these different approaches, and these are addressed in Chapter 6, which also explains some of the most important aspects of attribute database management.

The feature of GIS which is most commonly identified as separating them from other types of information system is their ability to perform explicitly geographic manipulation and query of a database. In terms of the data transformation model, these operations define the difference between GIS and cartographic systems, and they are examined in Chapter 7. Examples of the application of GIS technology to socioeconomic data manipulation are illustrated, including neighbourhood classification and matching census and postcode-referenced databases. It is the provision of such powerful tools as data interpolation, conversion and modelling which makes GIS so widely applicable and of such importance to geographic analysis.

The final aspect of GIS operation is the output of data in some form, either to the user or to other computer information systems. Chapter 8 explains the principles of data display and transfer, addressing both the technology used and the need for commonly accepted standards. Developments in data availability and exchange will continue to be particularly influential on the path of GIS evolution, both by attracting new users and by limiting the interchange of information between organizations. In both aspects, the available technology is considerably more advanced than the user community, and the need for good graphic design principles and more open data exchange is explained. This discussion also consid...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- Preface to the second edition

- Acknowledgements

- Glossary of commonly used GIS terms and acronyms

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Development of GIS

- 3. GIS Applications

- 4. Theories of GIS

- 5. Data Collection and Input

- 6. Data Storage

- 7. Data Manipulation

- 8. Data Output and Display

- 9. Towards a Socioeconomic GIS

- 10. Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index