1

CULTURAL NARRATIVES OF THE SUIT

Movements in the suits and movements of suits

The salwaar-kameez or Punjabi suit has traditionally been worn by women of North India and Pakistan and their diaspora overseas. These women were Hindu, Muslim and Sikh, originally sharing a regional territory and a common cultural base. While many women of all religions do also wear the sari in these areas, and some historically have worn only the sari, it is the suit that is seen as a distinctively Northern form of dress. It consists of three separate parts: kameez (shirt), salwaar (trousers) and chuni or dupatta (scarf or stole).

The suit appeared first in Britain from the mid-1960s onwards, a time of rapid growth of Asian communities as family groups consolidated themselves. Although Indian women had been a presence in Britain since the 1890s (Bhachu 1993a, 1993b), they had not previously constituted a critical mass and, publicly at least, had worn the sari in preference to the suit. Until the 1990s, then, the Punjabi suit was considered to be exclusively the dress of North Indian and Pakistani immigrant women. These immigrant clothes represented British Asians, who were not wanted on the British scene and were not welcome as citizens: they had been recruited as labour migrants (whom Britain was forced to accept because there were labour shortages after the Second World War) and because they were people resident in British colonies, with long-Standing British citizenship rights and passports. The suit represented a threat; the colonized had come to the land of the colonizers. In Britain, local white people often referred to it derogatively either as a sari or a pyjama- or night-suit. It was negatively coded, the highly charged clothing of marginal women, of newcomers who refused to assimilate the sartorial styles of the local white Europeans. 1 These women were considered by the local white population and also by many Asians who had adopted an assimilationist stance as not being in tune with the times. They were classified as orthodox women who were rigid in maintaining their ‘backward’ cultures, when they should, as seen from the outside, have been adopting local styles. There were many racial slurs levelled against them. They were taunted and labelled ‘Pakis’, regardless of whether they were Pakistanis or not, whether locally born or not, or from the earlier diaspora communities with children who had never been to the subcontinent.

Modifications of the suit have always been made when worn in diaspora settings and in some cases women have had to give up wearing it completely. In the early days of settlement in the new locations, there is no reinforcing critical mass of suit-wearing women who can buoy up each other’s sartorial confidence. For example, photographs taken in the 1920s in Vancouver (Canada) and California, the earliest centres of Punjabi settlement in North America, show Punjabi women wearing dresses which were long and modest, reaching just above the ankles, together with a headscarf, a short chuni, tucked inside the neckline or collars of their dress. Some also wore boots with these long dresses. I am told that stones were thrown at them by white racists for their different looks and sartorial styles. They had to adapt their clothes to be able to live their lives as safely as they could in overtly racist landscapes. Wearing a suit became a symbol of defiance for some North Indian and Pakistani women in the same way that the turban was for Sikh men. I now explore some of these narratives of ‘suit defiance’ in relating the movement of the suit from negatively coded ‘ethnic clothing’ to a global garment, fashionable both in the margins and within the mainstream.

Negatively coded suit stories of 1960s and 1970s Britain

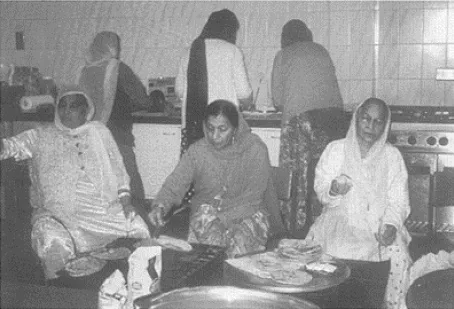

My mother was told when we arrived in London in the late 1960s that she should give up wearing the suit. Already fifty years old, she had started work in an electronic components factory making coils and circuit boards in south London. She was advised by her Punjabi friends to wear flared trousers with a short kameez, as commonly adopted by other suit-wearing women, to avoid the ‘night-suit’ jibes of local white people. This modified version of the suit would be worn to work with a short chuni or a longer woollen one in the cold weather: the flared trousers were also worn at home with the longer chuni that is worn with the classic suit. Punjabi Sikh women even wore similar modified outfits at the temple though I want to reiterate that many adhered to the classic suit styles and saris for community functions and social occasions like weddings. My mother, however, refused to modify her style even at work, wearing suits in the classic styles she had always worn and stitched for herself (see Figure 1.1).

By the 1970s, suits were worn increasingly by Punjabi women. Younger women tended to wear it stylishly for special social functions rather than as everyday wear. Always a supremely fashion-focused garment, adapted and interpreted according to local and international fashion trends all the time, the relative length of the kameez, the volume of material in the salwaar and the width of ponchays (trouser cuffs) changed continuously throughout the decade. In the 1960s and early 1970s, there was no concept of ‘readymade’ and the suits were made either by women themselves, buying material locally in Britain, or they had the suits made by Indian or Pakistani tailors when they went to visit the subcontinent. The women who had their suits made in this way tended to make far less design input. This is not to say that they did not wear inventive suits, because Indian and Pakistani tailors are attuned to fashion trends and create suits that are both elaborate in their embellishment and complex in their construction. However, there tended to be a greater amount of standardization of these suits, according to what was in vogue in India and Pakistan at the time. In addition, the design uptake of current trends was inevitably slower.

Figure 1.1 The heroines of my tale— older women wearing classically styled suits in a south London Sikh temple.

The most innovative suits were worn by women who either sewed themselves or who had access to good sewers, often from their own backgrounds. Although India-produced suits were made of lovely fabrics and colours with inventive embroideries to which diaspora women did not on the whole have access (unless they visited the subcontinent regularly), British Asian design interpretations were much more fashion-focused and responsive to local trends. It was, above all, the multiply-migrant East African Asian women who had the sewing expertise to put their local design exposures and personal inventiveness into practice with great speed. Direct migrant women simply did not have the same sewing tradition, coming as they did from service economies of longestablished professional sewing personnel, tailors and embroiderers, accustomed to meet their clothing demands. The multiple migrants, however, from East Africa, where there had been no comparable service economy, had grown up within the culture of sina-prona, where all clothes (and sheets, tablecloths, etc.) were home-made. The girls and women were systematically trained both at home by older female relatives and in local sewing schools. For them, an improvisational, hybridizing aesthetic was, of necessity, already in place. They further elaborated their skills in Britain because there was, as in the East African case, a need to do so. Surjeet, a multiply-migrant seamstress whose story I shall return to in Chapter 10, says that if she sees a suit on someone in the shop, she can make a copy of it in three hours from start to finish, including doing the hemming and putting on the buttons. This fast design uptake simply did not exist in the fashion economies of non-sewing women. But during the 1960s and 1970s there were few tailors and seamstresses who were ‘sewing for money’. People made their own clothes but few sewed for others beyond their own family and kinship circuits.

By the late 1970s, however, this situation was changing. Many more seam-stresses and tailors emerged as the Asian community established itself, ethnic confidence increased and more and more women started wearing suits. Crucially, many women now worked outside the home for wages. While lacking the time to sew themselves, instead they had their own money to spend according to their personal choices. The commodities they purchased encoded their cultural expressions and embodied their identities (see also Bhachu 1985 and 1991), and none more so than the suit,

The other dynamic for the growth of the ready-made suit market was the change taking place within the rituals of the traditional wedding, in particular a significant increase in wedding-gift exchange and elaborations in the wedding process. The increase in wedding-gift exchange was itself primarily the result of women participating directly in the labour market: the dowries of brides were elaborated because of their increased command of cash as waged workers, the elaborations taking the form of the bride’s personal accessories and clothing, including, of course, suits (see Bhachu 1985 for a London-based analysis of this). At the same time, the actual process of the wedding also became more complicated, with many more ritual and social functions connected to it, each requiring a different and often new outfit 2 (see Bhachu 1985, 1986, 1993a, 1993b).

The women who had kept the suit economy alive were often working-class immigrant women, and in particular the older ones who, like my mother, adhered to the styles that they had always worn. These staunchly Punjabi women from different religious backgrounds really did maintain the form they migrated with. They were and have remained confident about what they wore. In turn they socialized their daughters into this suit economy and so produced a new generation of hybridizing women from among whom would subsequently emerge fashion entrepreneurs such as Geeta Sarin and Bubby Mahil—pioneering, pathbreaking commercial agents in the public suit economy. Their stories will be central to Chapters 3 and 4.

My suit narrative

My own story of suit wearing serves as an example of being socialized by a woman who, as I have already shown, made few concessions to the local economy in which she was situated, despite pressures on her ‘to wear the trousers’ as she puts it. It also illustrates well the East African Asian hybridizing and improvisational aesthetic and the design process of negotiation and co-construction.

I had started wearing a suit in Kenya in my early teens, but only rarely. Most girls wore frocks or dresses derived from the fashions of the time. During the early 1960s, my generation of girls and young women wore the New Look frock and versions of the ‘twist dress’. We wore the New Look frock with a salwaar and chuni in the temple and at other times without the salwaar. I also wore the kurta and choost pyjama, the leg-hugging trousers which have folds of fabric at the ankle (the type of straight leggings worn by Indian Prime Minister Nehru). These were much in fashion in the mid- to late 1960s and were worn with high-neck kameezes made with long zips on the front opening. The zips had big plastic rings on the top, picking out colours from the kameez print. This interpretation of the kameez reflected the ‘pop culture’ style of the 1960s that was in vogue for young people of that generation—an example of the hybridizing aesthetic that British Asian women have elaborated in Britain in the 1980s and 1990s and which is played out in the new markets of the suit.

I moved to Britain with my parents in the late 1960s when I was fourteen. I went to local schools in south London in, essentially, very white suburbia. While a schoolgirl, I mostly wore standard school uniform and the clothes in vogue amongst my peer group. Then, when I was twenty-one, my mother made me some Punjabi suits which I wore at my sister’s wedding. My mother chose the material for these and made them up according to the fashion then current. They suited me and I liked wearing them. However, I wore them just for the wedding and a few other functions. A year or so later, she made me suits, the materials for which I chose and which she sewed for me according to the styles I liked wearing. She took me to the material shops I liked going to in central London, places like John Lewis, the department store on Oxford Street, and also Liberty’s, which specialized in William Morris and Paisley prints, fabrics with art deco motifs and tana lawn cottons. Of course at the time, I had no idea who William Morris was, nor of Liberty’s oriental imperialist history. (Liberty’s began trading in commodities ‘from the Orient’ in 1875, selling the goods brought back from India by the East India Company and from other Asian locations. Subsequently, it also specialized in products of the Arts and Crafts movement and art deco artefacts—see Adburgham 1975.) I simply liked their fabrics and bought them in their bi-annual sales. My mother would encourage me to select bold, clearly printed fabrics in vibrant colours. I was not clear or confident about my print choices then and would attempt to go for nondescript mish-mashed prints and colours. She had bold visual sense and was good at choosing fabrics that worked well in suits. She taught me a lot about mixing prints and colours that flow well in the suit silhouette, which has much combinational freedom because of its three separate parts. I am reminded of Sonia Delaunay’s early twentieth-century ‘simultaneous clothes’ inspired by the Modernist art movement, whose bold designs (made up of geometric patterns, circles within circles, concentric discs and prisms) flowed together in simple lines, enhancing the body’s movements. 3 My mother educated me into a colour and print palette that enabled the suit silhouette to flow similarly, a pedagogy of the suit economy in which she was experienced.

She also taught me how to cut and make a suit. At first, I would just make bits of the suit. Later, by my mid-twenties, I could cut and sew them completely. She told me continually that this was a skill I would need all my life in whichever country I was going to live. I had to master this skill of making a ‘basic suit’, she said. I have a large hardcover notebook of cutting instructions, measurements and fabric requirements, complete with pleat and dart information. I interpreted these early suits of the mid- to late 1970s using my own accessories, shoes, handbags, etc. She made me many more suits in later years, and others I made myself, until I started getting them made by seamstresses.

Our mother-daughter negotiations over details of collars, necklines and cuffs crucially enabled us to create styles that fitted my subcultural and subclass sartorial idiosyncracies. I sat with her all the time as she sewed, drawing sketches for her and showing her magazine pictures. She succeeded in getting me to wear a suit in a mainly white British context in which there were few other Asian women. She used cloth, thread and seams to connect me with a Punjabi dress form and also my ‘Punjabiness’. ‘You should wear our Punjabi dress with pleasure,’ she told me. ‘All cultures have their own dress which they wear in this country and in their own countries. You should remain strong in yourself. You should not live with fear. You should be strong in your culture. You should wear the Punjabi dress of your culture.’

It was soon afterwards that I started connecting with other Punjabis as a graduate student and also acquired a more proficient understanding of the Punjabi language which I learnt to read and write more fluently. Also, being at the School of Oriental and African Studies at London University, I was inducted into the South Asian scene much more. I was also doing my Ph.D. on a multiply-migrant British Punjabi community, preparing to do ethnographic fieldwork.

Soon after completing my Ph.D., when I started my first job in an academic research unit, I began to wear the suit more than any other clothes. I was working in the race and ethnic relations field and had been politicized by all its academic and policy machinations. My understanding of the operations of the race relations bodies and their personnel had grown dramatically from my research experiences. I understood more closely the mechanics of knowledge production and race-related policy making in these politically charged fields. For many people in this area, studying British Asian and Black communities was an academic game which they got into and out of depending on academic fashions. Their locations were and remain very different from those of us who were from the communities being studied and had lived our lives in difficult terrains that we were continuously struggling to navigate. I was angered by the liberal stances of articulate anti-racist sounding people who were actually quite racist in their day-to-day interactions with some of us junior ethnic researchers and in their conceptualizations of community dynamics. In this phase, my constant wearing of the suit became an ethnically defiant gesture on my part, in the face of the racism within this field and my increased abilities to decode the politically correct anti-racist public rhetoric spouted by the seemingly liberal theorizers and practitioners.

My mother’s sartorial and cultural interventions had come at a crucial moment of my life; her negotiations and her co-construction of the suit on my terms, being sensitive to my clothing styles, were critical in connecting me to my cultural base during a time that was difficult for us as recent migrants into an often hostile culture. The expression of overt ethnic registers like the suit was just not commonplace amongst young Asian women except within community social gatherings. I have worn the suit ever since, thanks to an astute and loving mother. She not only taught me how to make a ‘basic suit’ that I can elaborate on and sew in multiple ways, a sartorial template, but also gave me a template of cultural confidence, of learning to be myself on my terms regardless of the terrain.

I, too, as an adult have become a multiply migrant, now living and working in Massachussets, USA, where I find myself doing similar cultural work and engaging in the same negotiating aesthetics and sensibilities practised within the community contextsthat produced me. These diasporic databanks constitute my inherited baggage in constructing a life for myself as a new migrant, a new US citizen, producing my US-British-East-African Asian home. So much of this production of a cultural life in the US incorporates ‘bits and bobs’ transmitted to me by a savvy, culturally confident, negotiating mother, who inducted me into these economies, in part at least, through the suit as a expression of cultural pride.

A narrative of suit defiance

A further narrative of cultural pride and sartorial defiance that I want to relate concerns the 1980s pre-professionalization and pre-mainstreaming contexts of the suit. Rani Singh was raised in a neighbouring area of Southall, west London. She therefore had easy access to what constitutes the Punjabi capital in England and to suit-wearing women. After she finished school and college, in the early 1980s she got a job with a bank. As a young woman in her twenties, she would attend Christmas and New Year office parties in a Punjabi suit even though she was told often by her Asian and white friends alike that this w...