![]()

1

The key idea

Two celebrity circuits beat as one

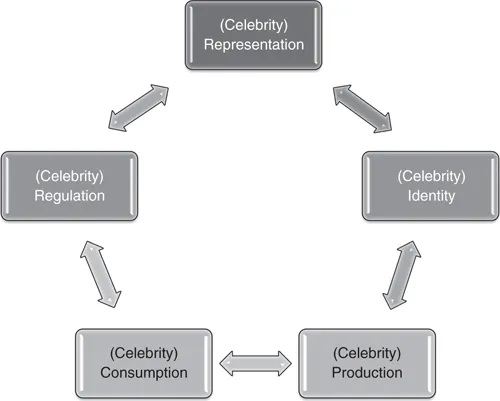

One of the challenges of defining the key ideas in a research field as broad as celebrity is ensuring that you assess its coordinates and computations across a number of theoretical positions and within overlapping, and sometimes competing, contexts. To meet these cross-wind challenges, the approach in this book is to draw on two dynamic models from two different modes of enquiry to get beneath and beyond the porous skin of celebrity culture. These models are the circuit of celebrity culture and the circuit of celebrity affect.

The Circuit of Celebrity Culture

The first model is drawn from British Cultural Studies and the pioneering work of sociology scholars from the Open University. The circuit of culture model is an intersecting, analytical schema that allows one to explore a cultural artefact, form, or phenomena across five dynamically ‘charged’ nodes or points. By employing the circuit of culture, one contends that it is only by passing a cultural form or formation through these nodes or points that one is allowed to adequately and fully understand the phenomena in question (du Gay et al., 1997: 3). No one node or point is more important than the other and they all intersect and cross-connect in a myriad of both competing and complementary ways, creating the spaces for the negotiation and transformation of meaning. The five nodes or points are as follows:

Representation

Or how phenomena are made meaningful through shared languages that people in a given culture readily understand. Representations are found in or through the language of films, books, music videos, blogs, photographs, newspaper stories, adverts and fashion – they are the very material out of which ‘things’ get their meaning, or as Stuart Hall puts it:

Meaning is produced within language, in and through various representational systems which, for convenience we call ‘languages’. Meaning is produced by the practice, by the ‘work’, of representation. It is constructed through signifying – i.e. meaning-producing practices.

(1997: 18)

Stars and celebrities are always representational constructs: their representations connected to, and dissected by, notions of possessive individualism, social class, gender, sexuality, race and ethnicity; and through commodity and consumer relationships. Celebrities are both ideologies and forms of a consumerist dream. For example, in the television advertising campaign for Chanel’s newest fragrance, Gabrielle (2017), American actress Kristen Stewart is seen breaking free from a cocoon-like sac and smashing through over-sized perfume bottles, before emerging to stand tall in front of a golden sun rising on the honey-coloured horizon. Stewart embodies the values of Gabrielle, the name of the founder of Chanel: feminine but powerful, mysterious but knowable. Stewart’s own star biography is transferred to the brand – she is independent, a trail-blazer, classically beautiful but also androgynous. Here gender is being post-feminised and turned into a commodity fetish – through the layering representational sheets of the possessive perfume, the figure of Gabrielle and the sexualised star image of Stewart.

Identity

Is the subject position that an individual comes to take up in society. People get their identities through both how they see themselves and how they are seen by others. Identity is never fixed and is a mix of active agency and normative and associative labelling or imposition, whereby certain identities are given or ascribed to people. Identity classifications occur on a daily basis through such discursive or meaning-making frameworks as social class, gender, race, ethnicity and sexuality. These identity positions are called classificatory systems and they permeate every area of the social world, including education, work, leisure and the arts and entertainment industries. Classificatory systems are not neutral: they are power-saturated and involve creating hierarchies that favour one group over another. As Chris Shilling and Patricia Mellor note, ‘discourses and systems of representations construct places from which individuals can position themselves and from which they can speak’ (1996: 5).

Stars and celebrities offer people particularly appealing identity positions that they are asked to ‘take up’, and are positioned to identify with. Stars and celebrities are often supericonic figures, who embody model identity positions that speak to certain psychic, cultural and economic needs, desires and aspirations and that fans and consumers are invited or positioned to hold and share. Stars and celebrities ‘interpellate’ their fans so that their subjectivities are, in part, defined by the ideologies that they stand for. The singer Beyoncé , for example, offers up a particularly powerful and arguably positive role model of black womanhood, which ‘shapes’ how black women see and feel about themselves. Beyoncé , of course, can also be read as mythologising the American Dream, or the myth that anyone can make it if they are talented and work hard enough (Cashmore, 2010). The reality for the majority of black Americans is quite the opposite.

One can see how closely representation and identity are articulated together: they are part of the same woven fabric of cultural meaning. In terms of celebrity culture, one begins to understand how celebrity and stardom produce representations and identities in the same registers of meaning. Representations create identities and identities are found in forms of representation: they are interlocking points on the circuit of celebrity culture.

Consumption

Refers to the way people interact with a whole range of products, services and social-cultural encounters, including how they watch television drama, respond to the news, engage with the social media and identify with certain film stars and not others, and the types of goods that are purchased. Consumption is also connected to questions of power and ideology since,

the consumption of cultural objects by consumers can empower, demean, disenfranchise, liberate, essentialise and stereotype. Consumers are trapped within a hegemonic marketplace.

(Denzin, 2001: 325)

Consumption is also, of course and conversely, active and resistant: people are shown to not passively respond to the media – celebrities included – but rather to subvert and transcode the very meanings associated with them. Consumption and reception involve both compliant and resistant readers, and readership is dependent on a whole range of contextual factors. Joshua Gamson (1994) has suggested, for example, that audiences consume celebrities with a degree of skepticism and knowing-ness. When it comes to a subcultural practice, such as fan fiction, we see celebrities re-inscribed or re-written, given new subject positions in the artwork, stories and amateur fan videos that are made of them. The slash fan work around Martin Freeman and Benedict Cumberbatch as Watson and Holmes, respectively, queers their relationship, opening up their representation to new and competing forms of masculinity and sexuality.

Production

involves the way goods, products and services, even ‘ideas’, are engineered, manufactured, marketed and sold. The cultural industries, for example, produce various forms, channels and modes of entertainment that include films, television programmes, streaming services, books, videos, as well as concerts, tours and the merchandising streams that accompany them.

However, one can also contend that today, the modes of production have themselves been thoroughly ‘culturalised’, so much so that one can write of a ‘cultural economy’ given the economic power given or afforded to global entertainment corporations. The transnational production of entertainment media has arguably created a ‘global cultural village’ through which the ‘whole world’ is connected to/by the production and consumption of cultural products.

Celebrity is seen to be one of the driving engines of the globalised production of entertainment media: whole franchises are built in and around celebrities, so that a star such as Taylor Swift isn’t simply a singer/performer but a revenue stream for a whole range of ancillary products and services. Taylor Swift has endorsement deals with international brands that include Keds, Diet Coke and Apple. Two particular sponsorship deals with UPS and AT&T were built around the release of her album, Reputation (2017), and promoted with the following press release and announcement:

UPS Delivering a Secure Logistics and Distribution Solution for Millions of Taylor Swift Album Deliveries to Retailers and Consumers Fans Can Win a Flyaway Package to an Upcoming Taylor Swift Show and Special Memorabilia Through Exclusive UPS Promotions. Two cultural icons, 10x GRAMMY winner Taylor Swift and UPS (NYSE: UPS), the world’s largest package delivery company, are partnering to deliver a new experience for customers, fans and employees in celebration of Taylor’s 6th studio album, Reputation.

(https://pressroom.ups.com/pressroom/ContentDetailsViewer.page?ConceptType=PressReleases&id=1503657046045-509)

AT&T Inc. has signed pop star Taylor Swift to an exclusive, multiyear partnership that includes a performance at a party the wireless and pay-tv service provider will host the night before the 2017 Super Bowl, the company said on Tuesday. The partnership includes exclusive performances and other content, AT&T said in a statement. Financial terms were not disclosed. Swift will headline the AT&T DirecTV Super Saturday Night concert in Houston on Feb. 4, the night before the 2017 Super Bowl … Exclusive content and portions of Swift’s concert will be made available to AT&T’s U-verse video and DirecTV customers after the show, AT&T spokesman Brett Levecchio said.

(https://finance.yahoo.com/news/t-signs-taylor-swift-multiyear-partnership-deal-184759145--nfl.html)

Such deals extend the way that sponsorship and partnership manifest: they move celebrity culture from soft commercial services, to logistics, and from roadways to information superhighways, ensuring that they occupy both material and digital spaces simultaneously.

Regulation

Is made up of two interconnecting components: external and internal governance. Regulation that is externalised is necessarily bound up with cultural politics and policy: it is made up from and out of rules, laws, agreed and shared rituals and certain moral and ethical codes. External regulation:

Is about the ways in which we routinely go about our lives, the ways in which we observe the ‘normal’ rules of behaviour in public – in the street, in cars and on public transport. Regulation is therefore ordinary; it is part of the routine that orders our lives each and every day.

(Thompson, 1997: 10)

Regulation is also equally about internalisation or what might be termed self-regulation. People continually regulate themselves, their social behaviour and everyday actions, even without knowing that this is what they are doing, so ‘routine’ and ‘natural’ one’s own self-regulation practices become. According to Michel Foucault, the ‘course of development in modernity (is) … from external regulation and external discipline towards self-regulation and self-discipline’ (1995: 198).

Internal regulation is about maintaining or gaining self-control and is concerned with how people become complicit in the way they monitor and ‘check’ their everyday behaviour. Nonetheless, regulation is also resisted by counter-regulatory practices. Body projects can be seen as an attempt to take resistant control of the gendered body, opening it up to non-binary norms.

When it comes to celebrity culture I have elsewhere suggested that the metronome can best take into account its regulatory impact on people’s everyday lives. Celebrities ‘beat out’ a particular rhythm, which shapes the way people orientate themselves in the world and the way they see themselves in society. Celebrities are both external and internal regulatory conduits, shaping behaviour, shaping the way fans and consumers mould their own life practices. For example, the cultural and psychic process of ‘girling’ is in part orchestrated through the way female celebrities regulate their own femininity: they draw upon and actively use health, beauty and lifestyle products to self-survey themselves. Female celebrities are often objectified and coded to-be-looked-at. They offer up a regime of looking and being looked at, which suggests objectification and the constant need to perform or embody a particular form of femininity, ethnicity and heterosexuality, which becomes normal and desirable.

In Japan, for example, there has been the recent phenomenon of a form of Bihaku embodiment that emerged among teenage girls who wanted to imitate the look of their favourite pop stars. Bihaku is a term, employed in marketing, which means ‘beautifully white’, and was first coined in the 1990s with the emergence of skin-whitening products and cosmetics. The desire to have whiter skin has a long tradition in Japanese culture but has gathered force with the rise of global celebrity and its associated chain of products endorsed by idealised white celebrities, such as Cate Blanchett. Pop stars such as Ayumi Hamasaki have taken on the glamour and appeal of white female stars and promote Bihaku products to solidify the s...