chapter 1

Science and society: knowledge in medicine

Kath Woodward and Stuart Watt

1 INTRODUCTION

What counts as knowledge? What do we mean when we say that we know something?

What is the status of different kinds of knowledge? In order to explore these questions we are going to focus on one particular area of knowledge—medicine.

How do you know when you are ill? This may seem to be an absurd question. You know you are ill because you feel ill; your body tells you that you are ill. You may know that you feel pain or discomfort but knowing you are ill is a bit more complex. At times, people experience the symptoms of illness, but in fact they are simply tired or over-worked or they may just have a hangover. At other times, people may be suffering from a disease and fail to be aware of the illness until it has reached a late stage in its development. So how do we know we are ill, and what counts as knowledge?

Think about this example. You feel unwell. You have a bad cough and always seem to be tired. Perhaps it could be stress at work, or maybe you should give up smoking. You feel worse. You visit the doctor who listens to your chest and heart, takes your temperature and blood pressure, and then finally prescribes antibiotics for your cough.

Things do not improve but you struggle on thinking you should pull yourself together, perhaps things will ease off at work soon. A return visit to your doctor shocks you. This time the doctor, drawing on years of training and experience, diagnoses pneumonia. This means that you will need bed rest and a considerable time off work. The scenario is transformed. Although you still have the same symptoms, you no longer think that these are caused by pressure at work. You now have proof that you are ill. This is the result of the combination of your own subjective experience and the diagnosis of someone who has the status of a medical expert. You have a medically authenticated diagnosis and it appears that you are seriously ill; you know you are ill and have evidence upon which to base this knowledge.

ACTIVITY 1.1

How many examples of different sources of knowledge does the above scenario offer? Can you find examples of personal knowledge, of knowledge of one’s own body, of expert knowledge and of pharmaceutical knowledge?

Where do you think these different knowledges might come from?

COMMENT

This scenario shows many different sources of knowledge. For example, you decide to consult the doctor in the first place because you feel unwell—this is personal knowledge about your own body. However, the doctor’s expert diagnosis is based on experience and training, with sources of knowledge as diverse as other experts, laboratory reports, medical textbooks and years of experience.

This example shows some of the different sources of knowledge we draw upon when seeking to know about health and illness; even to knowing whether or not we are ill. But how is this medical knowledge produced?

One source of knowledge is the experience of our own bodies; the personal knowledge we have of changes that might be significant, as well as the subjective experience of pain and physical distress. These experiences are mediated by other forms of knowledge such as the words we have available to describe our experience and the common sense of our families and friends as well as that drawn from popular culture. Over the past decade, for example, Western culture has seen a significant emphasis on stress-related illness in the media. Reference to being ‘stressed out’ has become a common response in daily exchanges in the workplace and has become part of popular common-sense knowledge. It is thus not surprising that we might seek such an explanation of physical symptoms of discomfort.

We might also rely on the observations of others who know us. Comments from friends and family such as ‘you do look ill’ or ‘that’s a bad cough’ might be another source of knowledge. Complementary health practices, such as holistic medicine, produce their own sets of knowledge upon which we might also draw in deciding the nature and degree of our ill health and about possible treatments.

Perhaps the most influential and authoritative source of knowledge is the medical knowledge provided by the general practitioner. We expect the doctor to have access to expert knowledge. This is socially sanctioned. It would not be acceptable to notify our employer that we simply felt too unwell to turn up for work or that our faith healer, astrologer, therapist or even our priest thought it was not a good idea. We need an expert medical diagnosis in order to obtain the necessary certificate if we need to be off work for more than the statutory self-certification period. The knowledge of the medical sciences is privileged in this respect in contemporary Western culture. Medical practitioners are also seen as having the required expert knowledge that permits them legally to prescribe drugs and treatment to which patients would not otherwise have access. However, there is a range of different knowledges upon which we draw when making decisions about our own state of health.

However, there is more than existing knowledge in this little story; new knowledge is constructed within it. Given the doctor’s medical training and background, she may hypothesize ‘is this now pneumonia?’ and then proceed to look for evidence about it. She will use observations and instruments to assess the evidence and—critically—interpret it in the light of her training and experience. This results in new knowledge and new experience both for you and for the doctor. This will then be added to the doctor’s medical knowledge and may help in future diagnosis of pneumonia.

Another source of knowledge here is the language and practices that create knowledge. The specialist language of the doctor produces meaning that has medically recognized status. Pneumonia is classified as a serious illness. It can be diagnosed according to an agreed set of symptoms. It has status in medical discourse as an illness. Part of the doctor’s authority rests on having privileged access to specialist language and classificatory systems. However, such language is increasingly entering into the discourses of common sense, for example, medical scientific research into stress-related illness has been popularized in everyday discourse. There is overlap but there are still boundaries between medical and scientific knowledge and what we have called common-sense knowledge. What might privilege the knowledge of medical science in defining illness? How do we distinguish medical science as an example of a scientific way of thinking and as a particular knowledge system? How is medical knowledge produced? Which knowledge counts and who has authority to validate what counts as medical knowledge? This chapter uses the example of medicine as illustrative of scientific knowledge to explore the social production of knowledge and the diversity of knowledge systems.

SUMMARY

Our example of medical knowledge illustrates the following.

- The need to ask questions; looking for evidence regarding those questions, interpreting this evidence and using this interpretation to act, and to change your understanding of the world.

- Many different sources of evidence may be used.

- Authority is an essential element of expert medical knowledge.

- Expert knowledge is socially sanctioned in a way that commonsense knowledge is usually not.

- All knowledge requires some social expression and socially accepted meaning, but some has more status than others.

2 KNOWLEDGE IN MEDICINE AND SCIENCE

What distinguishes medical science as a field of knowledge or set of knowledges?

Part of what distinguishes the patient from the doctor in the previous section is that the doctor has specialized medical knowledge that the patient lacks. This specialized knowledge is a collection of evidence and theories about our bodies, experience of diseases, how we respond to them and about how they can best be treated. But the general public also has knowledge of medicine—a ‘common-sense’ knowledge that is of a rather different kind. Significantly, doctors’ knowledge is marked by their having a licence to practise medicine. This gives them a social authority in the field of medicine that we— along with our faith healer, astrologer, therapist and priest—do not. So, has this special authority attached to the medical knowledge of professional physicians always been there, and if not, how has medical knowledge changed so that some is more valuable than the rest?

BOX 1.1 Medicine through the ages

This example shows how some acceptable approaches to medicine have evolved over the years.

Patient to Healer: I have an earache.

Healer in 2000 BC: Eat this root

Healer in 1000 AD: That root is heathen medicine. Say this prayer.

Healer in 1850 AD: That prayer is superstition. Drink this potion.

Healer in 1940 AD: That potion is snake oil. Swallow this pill.

Healer in 2000 AD: That pill is artificial. Eat this root

Source: Adapted from New Scientist, 6 September 1997

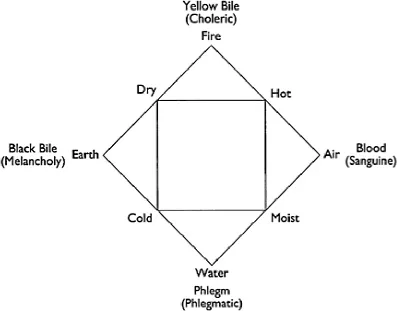

Even in ancient times, experts in medicine used their specialized knowledge to practise with drugs, surgery and a systematic and complex combination of prayers and spells, suggesting a link between science and religion. In the West for example, in the fifth century BC, medicine lost its religious and magical elements, and became more like what we today would call a science. At this time the Greek Hippocrates and others, drawing on Egyptian and near-Eastern medical practices, produced classifications of symptoms and objective accounts of ill health. Diseases were believed to have natural causes, resulting from an imbalance between four ‘humours’ or bodily fluids, perhaps caused by the seasons or the elements (see Figure 1.1). Physicians too changed; they needed knowledge of medicine, but also of logic, physics and even ethics—the sciences of the day.

FIGURE 1.1 Interaction between the elements, weather and disease in classical medicine

Subjective knowledge

Knowledge that depends on one person’s personal experience.

Objective knowledge

Knowledge which it is claimed is completely independent of whoever happens to describe and classify it.

This provided a forum for the development of Western medical science, which has been characterized by the establishment of socially sanctioned authority. Charles II founded the Royal Society in 1662 as an institution which allowed ‘gentlemen’ (and other men if they were invited, but no women) to discuss nature, philosophy and medicine separately from politics and religion. In practice, the Royal Society added two important elements to knowledge—a community, and claims to objectivity. This made knowledge produced within the Society more valuable and more authoritative, because it was believed to be more likely true than knowledge derived through other means. Subjective knowledge was seen as not as strong as objective knowledge, because it could not be confirmed by this community. Knowledge of the world was considered authoritative if it had been discussed at Society meetings or, even better, published in its journal, Philosophical Transactions.

The strength of this knowledge was largely due to its ‘gentlemanly’ origins. It was knowledge endorsed by the community of the Society and its members—the only audience and the only judges of this knowledge—who, by virtue of their independent economic status and high social position, were believed to be free of subjective biases. What constituted a ‘gentleman’ was changing during this time, but being male was still a requirement, as was possessing the right manners and character. Many, like Edmund Stone (see Box 1.2), were clergymen.

BOX 1.2 Willow bark and marsh fever

In 1763, the Reverend Edmund Stone of Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire, looked at willow bark, and investigated whether it could help alleviate the marsh fever that was common in the area. He had three reasons for looking at the bark of the white willow (Salix alba). First, its taste reminded him of ‘Peruvian bark’ (cinchona, a source of quinine) which was used to treat malaria. Second, there was ‘the general maxim, that many natural maladies carry their cures along with them, or that their remedies lie not far from their causes’. And finally, for Stone, ‘the intention of Providence’ in this link between the causes of illness and their remedies was also an influential factor.

Stone gave willow bark to about fifty people who had the symptoms of rheumatic fever, and found that it did seem to help. His report was published in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, but it was more or less ignored.

It is now known that salicin, the active ingredient in willow bark, has a similar effect to (and is related to) aspirin. Aspirin also had a herbal origin— it was derived from meadowsweet (Spirea ulmaria), which was also known to folk medicine as a pain reliever. Aspirin was patented in 1900, and has since become the most popular drug of all time.

ACTIVITY 1.2

What do you think the above example tells us about knowledge?

What kinds of knowledge was Stone drawing on in this work? What do you think he was producing?

Was he being objective?

COMMENT

Stone gave three reasons for investigating willow bark: reasons as diverse as his sense of taste, his knowledge of ‘common-sense’ medicine, and his biblical knowledge and religious faith. With these, and the evidence that he gathered and interpreted, he produced what was called scientific knowledge that willow bark was beneficial in alleviating the symptoms of marsh fever.

His interpretation of the evidence seems to have been affected by the expectations set up by, for example, his religious faith. It is difficult to disentangle the objective and the subjective. This is a general problem with scientific studies of medical treatments, an issue we will return to shortly.

Within the community of the Royal Society, new theories and methods could be brought into the field of medicine. It opened the door to new methods of gathering and using evidence that aimed to ensure that knowledge was more likely to be true. A systematic approach, open to new ideas, was badly needed in medicine. It didn’t seem possible to provide strong evidence—even proof—that a particular treatment was helping, and weak evidence (such as that provided by Edmund Stone) was not enough to convince the sceptics. The new methods offered the possibility of a scientific medicine, where knowledge of medicine was distinctly more authoritative and reliable than had been the case previously. This was because the new science and the new methods it embodied within communities like the Royal Society seemed to show a way of finding knowledge that could be supported with reliable evidence.

Medical knowledge had been changing through the ages, often quite radically, but there were few clear signs of progress. Mystical and religious influence...