Chapter 1

Individual and community action in HIV prevention

An introduction

Tim Rhodes

This book brings together a number of international contributions on the research, theory and practice of developing community-based HIV prevention interventions. This is achieved in three main ways. First, by examining the implications of research for understanding how and why individuals act as they do in response to the risk of HIV transmission; second, by discussing the implications of this research for developing health and HIV prevention interventions; and third, by exploring the aims and practice of innovative community-based HIV prevention among populations most affected by HIV and AIDS. The aim is to understand how individual actions are influenced by the social, cultural and political contexts in which such actions occur, and to explore how future HIV prevention interventions can target changes at the level of the individual as well as at the level of the community and wider social environment.

HEALTH PROMOTION AND BEHAVIOUR CHANGE

Recent developments in health promotion have advocated the need to balance individual and community action as a means of facilitating and enabling changes in individual and collective health status (Bunton and MacDonald, 1992). The ‘new’ public health movement of the 1980s promised to move beyond a biomedical understanding of individual health behaviour towards a new understanding which encompassed the social and environmental influences on individuals’ health choices, perceptions and actions (Ashton and Seymour, 1990). It was recognised that not only should health interventions target individuals with the aim of encouraging individual behaviour changes, but, where necessary, interventions should also encourage changes in the communities and social environments of which these individuals were a part. In response, ‘health promotion’ became re-defined as the intersectoral activity which encourages possibilities for individual action as well as community action and changes in the social and political environment (World Health Organisational [WHO], 1986; Bunton and MacDonald, 1992).

Health promotion theory thus conceives of health as being a product not only of individual actions but also of actions which take place in the social contexts and environments in which individual behaviours occur. Individual actions, and individuals’ desires or capabilities to change their behaviour, can be seen to be inextricably related to the ‘social actions’ of their communities, cultures or environments. The ‘choices’ individuals have and make about health, for example, are not simply a product of individual cognitive or rational decision-making. Rather, they are influenced by how other individuals think and behave and the social factors exogenous to individuals themselves which constrain or encourage the degree of ‘choice’ individuals can exercise.

The social factors which constrain or encourage individual choices and actions are many and varied. They may operate at the level of interpersonal interactions, as in the case of communication or ‘negotiation’ within sexual encounters where the actions or words of one individual have a direct bearing on the actions and words of the other. In behavioural situations where at least two individuals are present, choice of action is often a product of the interaction of individuals rather than something endogenous to individuals themselves. The social constraints on individual actions may also be community-oriented. An example of this is where group or community ‘norms’ influence what is considered to be appropriate, acceptable or ‘normal’ behaviour. Individual perceptions of social acceptability and ‘normality’ have a direct influence on how individuals behave. This is because individual actions which deviate from community norms are generally harder actions to make. Finally, the constraints on individual actions may also be politically oriented. An example of this is where local or state health and legal policies influence the degree to which individuals and communities can minimise their risks of health-related harm.

It is therefore an axiomatic principle of health promotion interventions that in order to encourage changes in the ways individuals think and behave it is often also necessary to encourage changes in the actions of their communities, cultures or environments. This is necessary so as to create the social conditions in which individuals are able—and can be encouraged—to exercise ‘choice’ about how they act in response to the risk of disease or illness. Health interventions are thus more likely to be effective if they encourage concomitant changes at the level of the individual, the community and the wider social and political environment.

HIV PREVENTION, RISK REDUCTION AND BEHAVIOUR CHANGE

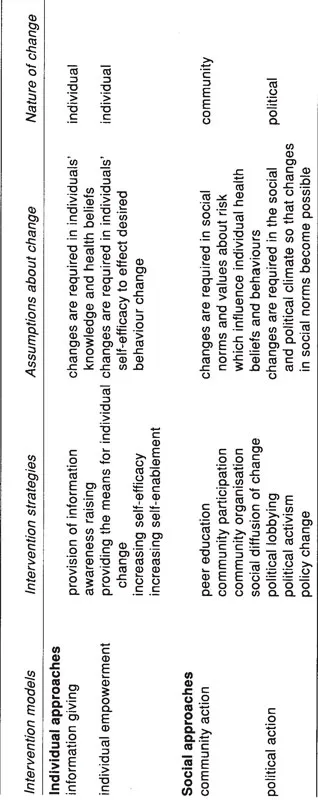

Following the general principles of health promotion, the prevention of HIV infection requires an integrated approach to encouraging behaviour change which encompasses individual and social models of health intervention and change (Figure 1.1 ). Individual and social intervention approaches make different assumptions about the factors which influence risk and health behaviour and how behaviour change is best achieved. Figure 1.1 illustrates how a comprehensive HIV prevention intervention strategy requires an integrated theoretical and methodological approach to encouraging individual, community and political action.

Figure 1.1 Individual and social approaches to HIV prevention

The HIV epidemic has brought new dimensions of risk. It has also brought about many changes. These changes have occurred in the everyday lives of the individuals and communities affected by HIV disease. They have also occurred in the ways health interventions aim to encourage risk reduction and behaviour change. The combination of medical uncertainty associated with the development of a vaccination against HIV and the public health urgency to prevent further HIV spread has encouraged the need for pragmatism in intervention responses which aim to prevent HIV transmission. This has facilitated what have come to be viewed as innovative styles of service delivery characterised by community-based interventions among populations most affected by HIV and AIDS.

For the most part, intervention responses have been based in a public health realism of the risks and dangers associated with an uncontrolled spread of HIV infection. The pragmatism which has characterised the emergence of HIV prevention responses in many countries has encouraged a recognition of the need to target changes in individual and community health. Yet while many HIV prevention interventions are ‘community-based’, they are rarely ‘community-oriented’. Contemporary HIV prevention responses have been overwhelmingly focused on targeting individuals with the aim of encouraging individual behaviour change. In reality, few interventions have adopted methods which simultaneously aim to encourage changes in the social contexts or environments where individual actions take place. Even less often have interventions attempted to bring about changes in the policy or the political environment.

This leads to the question of how much practical impact the rhetoric of health promotion and the new public health has had. The language of HIV prevention gives much credence to the notions of ‘enablement’, ‘empowerment’ and the ‘community’. Yet there are few HIV prevention interventions which systematically undertake ‘community development’ or which facilitate what can truly be seen to be ‘community action’ among members of affected communities themselves (Rhodes, 1994). The practice of most HIV prevention intervention falls short of the much-quoted ideals or principles of health promotion and the new public health movement (see WHO, 1986; Ashton and Seymour, 1990). The over-reliance on targeting individuals and individual behaviour changes alone restricts both the possibilities and parameters of change to individuals. What is needed are HIV prevention interventions that work with the community and not just in the community (Stimson et al., 1994). This demands more than the advocation of an integrated approach to encouraging individual, community and political action. It also demands an application of these intervention methods in practice.

PERSPECTIVES ON INDIVIDUAL AND COMMUNITY ACTION

This book considers the diverse practices of individuals and interventions in the context of perspectives from research on individual and community action.The chapters which follow provide an overview of research on the social context of risk behaviour and health intervention among injecting drug users, female stimulant users, gay and bisexual men and female sex-workers. The focus of discussion is on the development of interventions oriented towards community action and community change. This book hopes to make advances in the theory, method and practice of community-oriented interventions among populations most affected by HIV and AIDS.

Individual action, HIV prevention and the policy environment

Most psycho-social models of health behaviour are individualistic in focus in that they seek to explain and predict the health behaviour of individuals by reference to their personal characteristics. These models, which emphasise the ‘health beliefs’ (Rosenstock, 1974), ‘self-efficacy’ (Bandura, 1977) and motivations and skills (Rosenstock et al., 1988) of individuals to behave in certain ways, tend to assume that individuals’ decision-making on health choices is based on the perceived costs and benefits of action. Models of behaviour change that stem from these theories aim to enable individuals to have the knowledge and means to make healthy choices about their behaviour and lifestyles.

All of the chapters in this book share an appreciation of the limitations of individualistic models of health behaviour and behaviour change. They recognise that while providing pointers to individual behavioural intentions, they often fail to adequately capture the social dimensions or complexity of individual action. Chapter 2 (Gerry Stimson and Martin Donoghoe), for example, discusses the problems and possibilities associated with developing syringe exchange interventions. Such interventions aim to provide individuals with both the knowledge and the means to avoid HIV infection by injecting drugs safely. Yet, as Stimson and Donoghoe point out, despite the considerable success of syringe exchange interventions in the UK and Australian context, there are inherent limitations in these interventions by virtue of their individualistic focus. This restricts both the practical efficiency with which syringe exchange interventions can reach target populations and the effectiveness with which they can actually encourage individuals to change their injecting behaviour.

John Watters (Chapter 3) provides an additional perspective on how the social and political environment can influence the effectiveness of syringe exchange interventions. Whereas in the UK syringe exchange was adopted as part of a pragmatic public health response to prevent HIV and other blood-borne infections associated with injection, in San Francisco, as in many other states in America, the policy environment has impeded the development of such interventions. Watters traces the historical routes of resistance to syringe exchange in the United States, providing an incisive case-study of how the political environment can inhibit the development of what is seen, internationally, to be a pragmatic and effective method of HIV prevention. His chapter highlights the importance of community action in the absence of a ‘healthy’ policy environment and the necessity for political as well as individual and community change.

Richard Hartnoll and Dagmar Hedrich (Chapter 4) also examine the ways in which the local environment can influence the development of AIDS and drug policies and the implementation and impact of HIV prevention initiatives. Providing a case-study of the development of drug and intervention policies in Frankfurt, they explore how the aims and approach of HIV prevention interventions are influenced by tensions and dilemmas in the public and policy environment. Taken together, these three chapters aim to highlight how the nature of local and policy environments often have a direct bearing on whether and how interventions proceed. The effectiveness of HIV prevention not only depends on the theoretical or methodological approaches of specific interventions but also on whether the social conditions are conducive to action.

Community action and community change towards safer sex

There are two underlying reasons for developing community action interventions as a method of HIV prevention. The first concerns the inherent limitations of individually focused, one-to-one interventions in adequately reaching target populations within a specified community or social network. Community action interventions, in contrast, aim to encourage a system of peer support and participation which helps to overcome this problem. Second, as discussed in most of the chapters, interventions targeting individual behaviour changes alone are limited because they do not necessarily encourage the social conditions in which individuals can actually exercise ‘choice’. The aim of community change interventions are thus to bring about changes in the community norms and practices which impede individual attempts at risk reduction, and reinforcements in the community norms and practices which endorse safer behaviour (Rhodes, 1993). These interventions encourage not only individual change but ‘community change’ —change which is oriented towards groups, networks or communities of individuals (Bracht, 1990).

Chapter 5 (Sheila Henderson), for example, draws on the implications of qualitative research among women who use ‘dance’ drugs for developing interventions which are oriented to the specific cultural mores of the ‘rave’ and ‘club’ scene. She argues that the recreational use of ‘dance drugs’ is inextricably bound up with the subcultural norms and values of the rave and dance club and that these subcultures provide their own channels of communication and influence for the social diffusion of intervention messages.

The effectiveness of social diffusion interventions oriented towards community change is discussed further by Graham Hart (Chapter 6). In a chapter reviewing both the rationale and evaluation of community-oriented HIV prevention interventions among gay and bisexual men in the UK and USA, he demonstrates, by way of specific intervention case-studies, that community action interventions can be effective in encouraging gay communities to endorse and sustain a ‘norm’ of safer sex. This chapter serves as a useful pointer to how community action interventions can facilitate the ease with which individuals make changes in their sexual risk behaviour.

In contrast to intervention studies among gay communities, there have been fewer attempts to examine the possibilities for peer education or community organising initiatives among female sex-workers. Drawing on their ethnographic research among female street-sex-workers in Glasgow, Scotland, Marina Barnard and Neil McKeganey (Chapter 7) examine some of the key obstacles and opportunities which exist for encouraging peer education interventions among women prostitutes. Their research highlights the importance of qualitative research in understanding the interplay of individual actions and social context. This has implications both for the ways in which future interventions among prostitutes prioritise the risks associated with HIV ag...