- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Regional Policy and Planning in Europe

About this book

Regional Policy and Planning in Europe explores the ways regional policy and planning systems across Europe have been influenced by:

* economic and monetary union

* the impending enlargement of the European Union

* the devolution of administrative power from central government to regional authorities

* the increased importance of environmental and urban issues.

Presenting a comprehensive overview of the economic basis of integration, this book examines the evolution of various systems of government, planning and forms of devolution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Regional Policy and Planning in Europe by Paul Balchin,Ludek Sykora,Gregory Bull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

Urban Planning & Landscaping1 Introduction

This book is intended to facilitate the study of regional policy and planning, both within the context of the European Union (EU) as a whole and within the individual countries of Europe. During the last decade of the twentieth century, widespread concern was expressed about the integrative role of regional policy and planning in furthering the economic, social and political coherence of Europe. Within the context of the impending formation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and the enlargement of the EU, there was much debate over whether national and regional disparities in living standards and unemployment would be widened or narrowed in the early twenty-first century. Arguably of equal interest were constitutional developments, which were paving the way in many of the countries of Europe to various forms of regional government and regional planning. Whereas it had long been recognised that the competence for regional planning on a continental scale should appropriately be assumed by a supranational organisation rather than by a loose collection of national states, it was becoming clear that regional planning within individual countries could be handled more effectively by the regions themselves rather than by the centralised state. However, the formation of regional tiers of government and the development of various forms of regional planning were proceeding at a different pace from country to country. Only where cross-border planning was undertaken was there a possibility that a cohesive approach to regional planning would emerge – short of a uniform system of planning being imposed across the EU. Other important considerations included the degree to which investment in transport, information technology and energy would help or hinder the improvement in living standards in the peripheral and other disadvantaged regions, and the extent to which environmental improvement had an impact on regional development. Last, but not least, the economy and environment of urban areas are of considerable concern to policy-makers, particularly since 80 per cent of the population of the EU live in towns and cities rather than in the countryside. Urban areas, however, are inextricably incorporated into the economy of their regions, and consequently their problems often require regional rather than discretely urban solutions.

The Economic and Monetary Union and the enlargement of the European Union

On 25 March 1998, the European Commission confirmed that eleven Member States of the EU had, in effect, met the economic convergence criteria of the 1991 Maastricht Treaty and were thus eligible to adopt a single currency (the euro) in 1999 and become founding members of EMU. Of the other EU states, Greece had sought membership of EMU but had failed to comply adequately with the Maastricht criteria, while, for their own reasons, the UK, Denmark and Sweden were not among the first wave of applicants. However, although the membership of Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Austria and Finland was subsequently endorsed, commentators were quick to point out that in six of these countries (and most notably in Italy and Belgium), debt ratios were in excess of the Maastricht Treaty requirement of 60 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP). All eleven members, nevertheless, conformed with the requirement that budget deficits should not exceed 3 per cent of GDP, and were broadly on target in respect of long-term rates of interest and levels of inflation. Although, in most countries, progress towards meeting the Maastricht criteria was evident over the period 1993– 98, the European Monetary Institute (EMI) (the predecessor of the European Central Bank) was concerned about whether this would continue once EMU was under way in 1999 and in the early years of the new century.

In the larger Member States, there were major economic problems that needed resolving before the success of EMU in its early years could be assured. With the unification of Germany, the ratio of its national debt to GDP soared from 41.5 per cent in 1991 to 61.3 per cent in 1997, but although its budget deficit was forecast to be as low as 2.5 per cent in 1998 this might still have been too high to have curbed the debt ratio significantly. Substantial fiscal measures seemed necessary if the debt ratio was to be reduced to 60 per cent or below in a reasonable period of time. Although France (together with Luxembourg and Finland) complied with all the eligibility criteria for a single currency, its debt ratio had risen sharply from 35.5 to 58 per cent of GDP, 1990–97, mainly because of increased public spending on unemployment, health and pensions. To prevent the debt from rising further, its budget deficit needed to be decreased from 3 per cent of GDP in 1997 to 2.5 per cent according to the EMI. Italy was notable in having a debt ratio of 118 per cent of its GDP in 1997 – almost twice the Maastricht level of 60 per cent, but, because of far-reaching budgetary measures, the public deficit had been reduced dramatically from 9.5 per cent of GDP in 1993 to 2.7 per cent in 1997. However, according to the EMI, large and persistent budget surpluses will be necessary to reduce the debt ratio within an appropriate time. If, for example, Italy ran a recurring budget surplus of 3 per cent per annum, then a government debt of 60 per cent of GDP could be achieved by the year 2007. Although not among the first-wave applicants of EMU, the United Kingdom, nevertheless, would have been eligible for entry had it applied, since its debt ratio of 52 per cent of GDP in 1997 was well within the Maastricht requirement, and so too was its public deficit of only 1.9 per cent. Membership, however, would have necessitated a marked lowering of the UK's long-term interest rates – a downward movement incompatible with its aim of ensuring that the rate of inflation remained within target. However, on the assumption that the UK is able to continue to adhere to the Maastricht criteria and maintain stable exchange rates between sterling and the single currency for an appropriate period of time, there will be few economic obstacles in the way of the UK becoming a member of EMU very early in the twenty-first century.

On 30 March 1998, less than a week after the Commission had confirmed the initial membership of EMU, the Council of Ministers of the EU met in Brussels to begin accession talks with their counterparts from five Central and East European candidate states (the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia), together with Cyprus. From the outset it was clear that new members could not expect a British-style opt out from the single currency, nor, prior to membership, expect to receive EU funds (of up to 3 billion ECU) to develop transport links and other infrastructure facilities, modernise agriculture and assist business development, unless the relevant candidates closed down their Soviet-era nuclear power stations, put VAT systems in place, granted full citizenship rights to ethnic minorities and set up fully independent judiciaries.

Clearly, because the EMU will impose fiscal and monetary constraints on the macro-economic policy of member countries, the extent to which regional aid can be funded will be strictly limited. With the enlargement of the EU, funds will be spread more thinly, and many of the poorer regions in Western Europe (several with large agricultural sectors) will cease to be eligible because aid will be diverted to even-poorer members in Central and Eastern Europe (with even larger agricultural sectors) (Table 1.1). However, in determining the distribution of regional aid for the period 2000–06, Ministers, first and foremost, will need to focus their attention on economic inequalities within the existing Union – most notably in respect of the substantial disparities in GDP per capita and rates of unemployment.

Regional disparities in living standards and unemployment

Within the EU, many peripheral areas were economically underdeveloped and were lagging behind the rest of the Union in terms of both GDP per capita and employment. There is evidence that peripherality undoubtedly has an adverse effect on ‘the levels of innovation, new firm formation and the extent of external control between regional economies’ (Tomkins and Twomey, 1994: 157). Broadly, Greece, southern Italy (including Sardegna and Sicilia), Corse, Spain, Portugal, Ireland and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland were all areas so disadvantaged. All had a disproportionately large agricultural working population and a smaller than average workforce employed in industry. Other areas where development was lagging behind included the Eastern Länder of Germany which, with their old industrial base and small service sector, contained a concentration of industrial and comparatively unskilled labour. There are also a number of disadvantaged areas which, although are non-peripheral, have rates of unemployment and industrial employment higher than the EU average and where industrial jobs are in structural decline. A large number of these areas exist within the coalfield regions of North-West Europe, for example, Central Scotland, the north-east of England, West Cumbria, South Yorkshire, the north-west of England, South Wales, the Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Est regions of France, parts of the Région Wallonne in Belgium, and Nordrhein-Westfalen in Germany. Aparr from a decrease in coalmining, other staple industries were also in decline in these areas, such as iron and steel manufacture, shipbuilding and textiles. Each industry faced changing patterns of competition, demand and output, and since the 1960s coalfields in Western Europe as a whole ‘have lost 57 per cent of their production and 82 per cent of their workforce, while the iron and steel industry has lost 60 per cent of its workers’ (Tomkins and Twomey, 1994: 157). Away from the coalfield regions, areas of industrial decline can also be found in, for example, sub-regions centred on Barcelona, Torino, Wien and in parts of Central and North-East Sweden. Throughout the EU, there are also large numbers of disadvantaged and vulnerable rural areas with a low level of socio-economic development. In, for example, large parts of western and southern France, north-eastern Spain, central Italy, northern Germany, the south-west and north of England, Wales and the borders of Scotland, there is a high proportion of employment in agriculture, a low level of agricultural incomes, and either a low population density or a high degree of out-migration.

Table 1.1 Gross domestic product per capita and employment, EU and Central and Eastern European countries, mid-1990s

In contrast, there are many regions within the core of EU where economic development is proceeding at a rapid pace and where the average level of prosperity is high. Based disproportionately on high-tech and service employment, and research and development activity, these areas include, for example, the contiguous Länder of Hessen, Bayern and Baden-Württemburg, and the neighbouring regioni of Lombardia and Emilia-Romagna, together with the non-contiguous regions of Hamburg, Bremen, Östosterreich, the Ile de France and Région Wallonne.

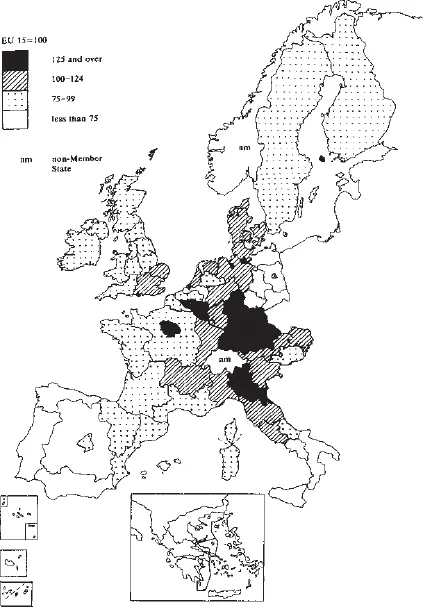

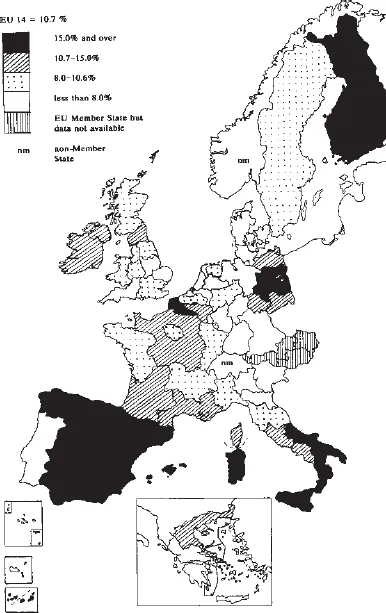

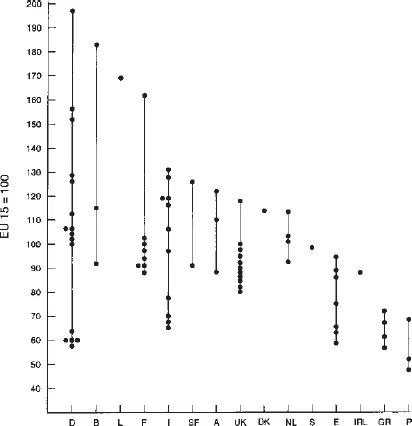

Table 1.2 and Figure 1.1 show the extent to which living standards are disparate throughout the EU. Whereas, the GDP per capita of the most prosperous region, Hamburg, was 96 per cent higher than the average for the EU in 1994, in the least prosperous region, the Açores, the GDP per capita was as low as 48 per cent of the EU average. Taking the average for the top ten regions, the GDP per capita was as high as 53 per cent above the EU average, but as little as 58 per cent of the EU average for the lowest ten regions. Disparities in rates of unemployment were similarly substantial. Table 1.3 and Figure 1.2 indicate that in 1995 unemployment ranged from as little as 2.7 per cent in Luxembourg to as much as 31.8 per cent in Sur. Taking the lowest ten regions, the average unemployment rate was as low as 5.5 per cent, but in the top ten regions was as high as 22.7 per cent. The spatial distribution of long-term unemployment, moreover, very broadly overlaps the pattern of overall unemployment. Taking the ten regions with the smallest amounts of overall unemployment, the proportion of long-term unemployed averaged only 45.4 per cent of the total, whereas within the ten regions with the largest amounts of overall unemployment, the proportion that was long term amounted to as much as 58.9 per cent.

Clearly within the Member States of the EU, regional disparities in GDP per capita and unemployment are not so marked as in the Union as a whole. There are, however, substantial differences in degrees of disparity between countries (Figures 1.3 and 1.4). Whereas in 1994 the GDP per capita in Germany ranged from 96 per cent above the EU average in Hamburg to only 57 per cent of the EU average in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (a 109 percentage points difference), in Greece the GDP per capita ranged from only 73 per cent to 57 per cent of the EU average (a 16 percentage points difference). Rates of unemployment also varied substantially between countries. Whereas in 1995 the rate of unemployment ranged from 6.0 per cent of the working population in the Nord Est region to 25.9 per cent in Abruzzi-Molise (a difference of 19.9 per cent), in the Netherlands unemployment ranged from 6.9 per cent in Zuid-Nederland to only 8.9 per cent in Noord Nederland.

Table 1.2 Gross domestic product per capita, regions of the EU, 1994

It is widely accepted that, both within individual countries and the EU as a whole, marked regional disparities in living standards and unemployment are economically disadvantageous. In areas where GDP per capita is high and unemployment is low, it is probable that economic growth will be at a comparatively rapid rate, there will be a consequential shortage of labour, land and capital in relation to demand and there will be a tendency for cost-push inflation or demand-pull inflation or both to be endemic. Conversely, in areas where GDP per capita is low and unemployment is high, it is probable that the rate of economic growth will be comparatively slow and that labour, land and capital will be under-utilised. However, with some regions being rich and some being poor, and with some suffering from high unemployment while others have low unemployment, the application of corrective macro-economic policy at times of economic instability can easily have perverse effects. If the national or EU economy is suffering from recession, the introduction of a battery of monetary and fiscal measures to reflate the level of aggregate demand, while benefiting the poorer regions, might very easily over-heat areas of high GDP per capita and low unemployment. Conversely, when inflation is endemic, the use of monetary and fiscal policy to disinflate aggregate demand might very quickly exacerbate the problems of areas with a low GDP per capita and high unemployment. Clearly, a more spatially balanced pattern of living standards and unemployment levels would enhance the efficacy of macro-economic policy when applied to the task of countering inflation or recession on a national or EU scale, and arguably the narrowing of economic inequalities would provide a means of promoting social harmony and political good-will between the regions and Member States of the EU.

Figure 1.1 Gross domestic product per capita, EU, 1994

Table 1.3 Unemployment rates, regions of the European Union, 1995

Figure 1.2 Unemployment, EU, 1995

Figure 1.3 National disparities in gross domestic product per capita, 1994

Structure and content

Although there are many excellent books in print both on the geography of the European Union and on urban and regional planning in Europe (particularly J. Cole and F. Cole‘s A Geography of the European Union, P. Newman and A. Thornley‘s Urban Planning In Europe, and R.H. Williams’ European Union and Spatial Policy and Planning), there is an absence of a wide-ranging text covering regional policy both nat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The economic basis of integration

- 3 Introduction to government and planning systems

- 4 Unitary states with centralised planning powers

- 5 Unitary states with planning powers substantially devolved to the municipalities

- 6 Unitary states with planning powers devolving to the regions

- 7 Unitary states with planning power substantially devolved to the regions

- 8 Federal states with planning power largely vested in the regions

- 9 Transition states of East Central Europe

- 10 Infrastructure, the environment and regional development

- 11 Urban areas

- 12 Conclusions

- References