1 Introduction

Eighteen years spanned the successive Conservative governments that started with Mrs Thatcher’s election victory in 1979. Eighteen years span the successive Workplace Industrial Relations Surveys that started with our first survey in 1980.

This happy coincidence of timing allows us—almost compels us—to use the full range of information from the survey series to assess the impact of the Conservatives’ policies and initiatives upon employment relations in Britain. The first survey was undertaken before the incoming government’s initial ‘reforms’ in 1980. Our fourth survey was completed before the first wave of primary legislation enacted by the incoming Labour government of Mr Blair. The intervening eighteen years saw a host of changes affecting people at work. Successive Acts of Parliament sought to weaken trade unions and give employers and managers more power in the labour market and in the workplace. Tripartite national institutions were progressively abolished and new bodies created with employers and consumers the dominant interests. Developments in the world economy impinged greatly upon the structure and operations of industry and commerce. Privatization shifted whole sectors of the economy from public to private ownership as part of a broader programme of economic liberalization. ‘Flexibility’ became a goal and a guiding principle of government labour market policy. Social and demographic trends brought about changes in the composition of the labour force and in the types of jobs on offer and taken up. ‘Human resource management’ began to replace ‘personnel management’ and ‘industrial relations’ in the discourse of management and employee relations practitioners as well as among academics. Job insecurity became a dominant concern of many in employment; ‘employability’ the panacea for those who lost their jobs.

Did all this signal a transformation in British employment relations? Were the changes that took place so widespread and fundamental that to characterize them as a transformation is justified? Was it really ‘All Change at Work?’

Our aim in this volume is to set out as much empirical evidence as we can from the Workplace Industrial Relations Survey (WIRS) series to answer this broad question. The WIRS series comprises a set of four national surveys of British workplaces, in which key role-holders at each workplace (most notably, the senior person dealing with industrial relations, employee relations or personnel matters) provide information on the nature of employment relations at their place of work. The surveys themselves took place in 1980, 1984, 1990 and 1998.

Many of the changes evident from the first three surveys in the series have been documented to some degree in our earlier reports (Millward et al., 1992; Millward, 1994a) and in further explorations of the data by other analysts.1 Commentators, teachers and researchers appreciated the great advantages of having results from a consistently designed series of surveys upon which to base those analyses. Yet in contemplating a fourth survey, many thought that so much of the landscape had changed that surveying it with the same instruments would provide a partial or misleading picture. Hence, when the four organizations that had been responsible for mounting the 1990 WIRS came together to discuss collaborating on a new survey, a radical rethink of its focus and design was high on the agenda. The four organizations were the Department of Trade and Industry (having taken over responsibility for industrial relations matters from the Department of Employment), the Economic and Social Research Council, the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service, and the Policy Studies Institute. Each of the four sponsors supported the discussions that led to the refocusing and redesign of the survey; those discussions are well documented elsewhere (Cully, 1998). One outcome was the renaming of the 1998 survey as the Workplace Employee Relations Survey (WERS), although we still use the original title (WIRS) to refer to the first three surveys and when referring to the series as a whole. However, the more crucial outcomes, in terms of our focus in this volume, were decisions as to how new elements could be added to the design and content of the latest survey without detracting from the essential comparability with the earlier surveys in the series.

We believe that, given the inevitable constraints of time and money, the updating of the survey instruments has been achieved with considerable success. Core topics have been retained, providing invaluable consistency, but important new elements have also been introduced into the survey.2 The research team’s companion volume (Cully et al., 1999) draws on the wealth of data available from the 1998 WERS to provide an initial exploration of the state of employment relations at the end of the 1990s. Yet it contains only a brief overview of the changes that can be observed over the eighteen years since the first survey took place in 1980 (Millward et al., 1999a).

Change, however, forms the sole focus of this book. Having achieved a balance of old and new in the 1998 survey, we are now able to compile a substantial bank of reliable data on workplace employment relations that stretches back over nearly two decades. The aim of this book is to present and interpret those data and, in so doing, provide an informed assessment of the changes that have taken place in workplace employment relations in Britain between 1980 and 1998.

The essential features of the WIRS design

Before providing some detail on the data and methods that will be employed in our analysis, it is necessary to say a little about the design of the Workplace Industrial Relations Surveys. Further detail may be found in the Technical Appendix.

In each of the surveys in the series, the establishment or workplace constitutes the principal unit of analysis. A workplace is defined as comprising the activities of a single employer at a single set of premises; examples might include a single branch of a bank, a car factory, a department store or a school. The central focus of the survey series has been the formal and structured relations that take place between management and employees at the workplace, although this focus softened in WERS98.

The geographical scope of each survey in the series extends to cover Great Britain, namely England, Scotland and Wales. The surveys cover workplaces in the private and public sectors and span all sectors of industry with only limited exceptions. The significant omissions are agriculture, forestry, fishing and deep coal mining.

Very small workplaces are also excluded for practical reasons. The 1980, 1984 and 1990 surveys limited their scope to workplaces with twenty-five or more employees, this being seen as the threshold below which it would be difficult to administer a survey of structured relations. After a fresh investigation of the practicalities, the 1998 survey dropped the threshold from twenty-five employees to ten. However, to retain consistency with earlier years we use only those workplaces from the 1998 survey employing twenty-five or more workers. Overall, the workplaces represented by each of the surveys are estimated to account for around 70 per cent of all employees in Britain in each of the survey years.

Each of the four cross-section surveys in the WIRS series is based on rigorous sampling methods, designed to ensure that results from the survey are representative of the total population of workplaces from which the sample is drawn. The samples themselves have been taken from frames considered to be the best available at the time, namely the Censuses of Employment of 1977, 1981 and 1987 and the Inter Departmental Business Register (IDBR) of 1997. Differential sampling by employment size has been used throughout the series to permit separate analysis of larger workplaces, which employ the majority of workers. Some modest differential sampling by industry was also introduced in 1990 and the principle extended in 1998. In each case, weights have been used in analysis to compensate for unequal probabilities of selection. The representativeness of the results and quality of the data are further promoted by the investment of considerable time, energy and financial resources into the conduct of fieldwork. Carefully thought-out contact procedures, the deployment of professional, trained interviewers and meticulous data verification have been central features throughout the series. The high response rates that have been achieved—at least 75 per cent for each survey—are a testament to the efforts of the fieldwork organization (Social and Community Planning Research) and give a clear indication of the quality of the resultant data.3

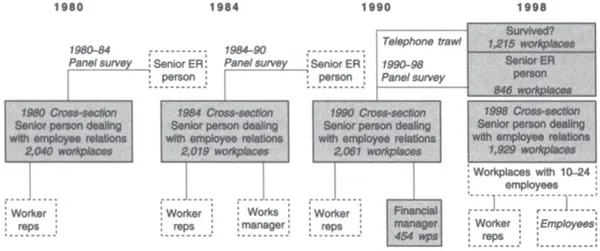

The surveys themselves obtain information about the workplace through face-to-face interviews with key role-holders, using a standardized questionnaire. The main respondent at each establishment is the senior person dealing with industrial relations, employee relations or personnel matters, based on the principle that they are the most informed and reliable single source of information about employment relations at that workplace.4 In some cases, particularly small establishments, this person is not a personnel specialist but may be a general manager, senior administrator or head teacher. Each survey has also included interviews with worker representatives, where present, though these data are not utilized in this volume, since changes in the selection procedures used in successive surveys mean that the samples are not comparable over time. Individual surveys have also included interviews with production managers (1984), financial managers (1990) and a survey of employees (1998) but, in the absence of time-series data, this information has also been largely ignored for the purposes of our analysis of change.

Thus, whilst there have been variations in peripheral elements from one survey to another, the principal features of the WIRS design have remained constant throughout the survey series. This consistency, when allied to a significant degree of continuity in questioning, means that the WIRS series represents the largest, most comprehensive and authoritative research resource available to those wishing to chart developments in workplace employment relations in Britain over the past twenty years.

Elements of the survey series employed in this volume

Having outlined the broad nature of the surveys, we now give some detail about those particular elements that will be employed in our analyses and explain how each can assist us to chart and explain recent changes in British employment relations. Figure 1.1 provides an illustration of the various components of the WIRS series, with the shaded cells representing those elements of the series that will be focused upon in this volume. Our analyses are based on what is, potentially, a very powerful combination of time-series and panel data.

WIRS time series 1980–98

The time series is formed from the interviews with the main management respondent in each of the four cross-section surveys. In Figure 1.1 these are represented by the four large cells labelled ‘Senior person dealing with employee relations’. In each case, the cell also contains the total number of achieved interviews. As noted above, little of the information obtained from interviews with other role-holders is used, except for those elements of the 1990 survey of financial managers in which selected questions from the main interview were asked of this respondent instead of the personnel manager.5

Figure 1.1Elements of the survey series employed in our analysis

Notes

- In each year information was obtained from each of the specified role-holders via face-to-face interviews, with two exceptions. One exception was the interview that established the survival status of those 1,215 workplaces from 1990 that were excluded from the 1998 panel survey, where a telephone interview was conducted with the first informed contact at the establishment. The second exception was the 1998 survey of employees, conducted by means of a self-completion questionnaire.

- In 1990, we only use that part of the interview with the finance manager in which the respondent answered questions on behalf of the personnel manager. Data concerning the financial status of the establishment, obtained only from financial managers, is not used in this book.

This time-series dataset makes the most of the continuity present within the survey series by providing direct comparisons of employment relations practice at four specific points in time over the past two decades. It is therefore possible to investigate the degree of change or stability in the incidence of specific practices over time, both in aggregate and within particular sectors of the economy or types of workplace. One can also assess the extent to which historical relationships—such as that between workplace size and union presence, for example—have changed over the period of observation.

However, whilst comparisons between cross-sections can reveal interesting patterns of change, these represent the combined, ‘net’ outcome of what may amount to many different processes acting concurrently. Being simple ‘snapshots’ of practice at a particular point in time, cross-section data are unable to identify the means by which such ‘net’ changes have occurred. One possible explanation is that workplaces forming part of the population at both time-points have altered their behaviour in some way, derecognizing their unions for example. This may or may not be linked to a change in some other feature of the workplace that is known to be associated with the matter in question, such as a change in its size. A second possible explanation for ‘net’ changes over time is that, as workplaces leave a particular sector of the economy and are replaced by new establishments in that sector, the incidence of the practice in question may change as a result of differences in behaviour between the two groups. For example, large manufacturing plants that have closed down between the two time-points may have been more likely to recognize trade unions than new ones that were set up during the same period. The third, remaining explanation may be that ‘net’ change has arisen purely as a result of changes in the composition of the population. If, for example, trade union recognition is more prevalent in manufacturing than in services, and service-sector workplaces are becoming numerically more dominant in the population, this shift in the structure of industry could, all other things being equal, bring about a net change in the aggregate level of union recognition.

Of course, it is also the case that, where time-series results show stability between two points in time, there may none the less be considerable change beneath the surface. Any or all of the three types of change may be taking place within the population. The stability seen in the time series then merely reflects the fact that they have, in combination, served to cancel each other out at the aggregate level.

Whilst it is true that changes of the types mentioned above can be revealed to some extent within cross-section surveys through the use of retrospective questions, these are unlikely to be reliable when one is concerned with matters of detail or when lengthy periods of recall are required. In addition, the usual practice of drawing fresh samples for each cross-section means that information is not collected about the survival of different types of establishment over time. Hence, the role played by workplace closures, for example, in bringing about ‘net’ change remains obscure. These problems can be overcome by survey designs that separately identify three categories of workplace within the changing population:

- Workplaces that are present within the survey population at both t1 and t2(here termed ‘continuing workplaces’);

- Workplaces that are present in the survey population at t1but not at t2 (‘leavers’); and

- Workplaces that are not present in the survey population at t1 but which are present at t2(‘joiners’).

Such a design exists within the WIRS series for the period 1990–98. The design and its uses are explained below, first considering the 1998 WERS Panel Survey of continuing workplaces.

The 1998 WERS panel survey

A panel survey allows one to measure ‘within unit’ change—that is, change which occurs within workplaces that continue in operation over the period of observation. The...