- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding in Mathematics

About this book

The concept of understanding in mathematics with regard to mathematics education is considered in this volume. The main problem for mathematics teachers being how to facilitate their students' understanding of the mathematics being taught. In combining elements of maths, philosophy, logic, linguistics and the psychology of maths education from her own and European research, Dr Sierpinska considers the contributions of the social and cultural contexts to understanding. The outcome is an insight into both mathematics and understanding.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralChapter 1

Understanding and Meaning

We are in a class of the fourth grade. The teacher is dictating: ‘A circle is the position of the points in a plane which are at the same distance from an interior point called the centre.’ The good pupil writes this phrase in his copy-book and the bad pupil draws faces, but neither of them understands. Then the teacher takes the chalk and draws a circle on the board. ‘Ah’, think the pupils, ‘why didn’t he say at once, a circle is a round, and we should have understood.’ (Poincaré, 1952)

Understanding

The Word ‘Understanding’ in Ordinary Language

The word ‘understanding’ is used in very many forms and expressions in informal speech. We say that a person ‘understands’ something, we speak of a person’s ‘understanding’ of something, and of the various ‘understandings’ people may have. We also speak of ‘mutual understanding’, of understanding somebody’s utterance or somebody’s writing, of understanding a word, an expression, a concept, a phenomenon. We qualify understanding as ‘good’, ‘deep’, ‘poor’, ‘complex’, ‘significant’, ‘full’, ‘incomplete’, ‘intuitive’, or ‘wrong’. We sometimes speak of ‘some’ understanding to say that this understanding is not yet very elaborate.

It is often claimed that the word ‘to understand’ is highly ambiguous (Kotarbinski, 1961, p. 128). Indeed, it is certainly not the same mental and emotional experience to understand the phenomenon of sunset and to understand a poetic description of a sunset. It is not the same to understand the sun as a bright sphere that travels across the sky from dawn to twilight and to understand the sun as the star around which gravitate the Earth and other planets of our planetary system. In this case we speak of two ‘ways of understanding’ or two different ‘understandings’ of one and the same thing.

‘Understanding’ can be thought of as an actual or a potential mental experience, as Kotarbinski pointed out (ibidem). For example, when we say that a person, who knows his or her multiplication tables, understands the thought that ‘7 times 9 is 63’, we may mean that the person actually, at this moment, thinks of ‘7 times 9’ and ‘63’ and considers them as equal, or that he or she is capable of so doing at any time, having reflected upon it already in the past.

There are, then, actual mental experiences, which we might call ‘acts of understanding’ and there is ‘an understanding’ which is a potential to experience an act of understanding when necessary. ‘Understandings’ thus seem more to belong to the sphere of knowing: they are the ‘resources’ for knowing.

An act of understanding is an experience that occurs at some point in time and is quickly over. But, especially in education, we also speak of understanding as a cognitive activity that takes place over longer periods of time — then we sometimes use the term of ‘process of understanding’ in which ‘acts of understanding’ mark the significant steps while the acquired ‘understandings’ constitute props for further development.

Understanding … What?

Acts of understanding, understandings, processes of understanding can all differ by that which is understood: an expression of language, a diagram, a concept, a theorem, a theory, a judgment, somebody’s thought, a phenomenon, a situation, a problem …

In the context of mathematics, we often speak of understanding ‘mathematical concepts’ in general or of understanding specific mathematical concepts such as number, quantity, volume, function, limit of a sequence, linear independence of vectors etc. However, other things are mentioned as objects of understanding as well.

Let us consider, as an example of a text concerned with cognition in the mathematical field, the 1991 article of James G. Greeno, and find the various uses the author is making of the word ‘understanding’ and its derived forms. Let us start with the question: what appears there as ‘objects of understanding’?

In the first instance of the use of the word ‘understanding’ in the article, it is associated with ‘patterns’: ‘understanding subtle patterns’. Later the author mentions understanding of ‘concepts, notations and procedures’, ‘equivalences’ (e.g., of 42 and 6•7, 2/3 and 4/6, y = 6 – 3x and x/2 + y/6 = 1, etc.), ‘relations among numbers and quantities’, ‘how mathematics is related to situations involving physical objects, quantities of money and other concrete things’, ‘problems and situations’, ‘language’, ‘language of mathematics’, ‘instructions’, ‘the linear structure of positive integers’, ‘relations between places in the environment that are represented by the symbols on the map’, ‘meanings [of procedures for manipulating notations]’, ‘reasonings’, ‘one’s physical position in an environment’, ‘concepts and principles’, ‘linguistic representations of concepts’, ‘theoretical entities and processes’, ‘the difference between an object and the thought about that object’, ‘the sequence of numerals’, ‘mathematical concepts’, ‘a phrase’, ‘mathematical questions’, ‘metamathematical views’.

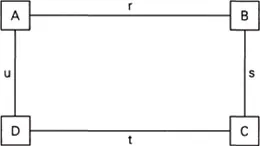

Figure 1: The pattern of the problem of Luc and Michel

Confusion Between the Thing I Want to Understand and That on Which I Base My Understanding

If I say ‘I understand the pattern’ (of a class of problems, for example) I may mean that the object of my understanding is really the pattern, or I may mean that I intend to understand the class of problems and the perception of some common pattern in these problems constitutes my understanding of it — the pattern founds my understanding of the class of problems. In the former case, I reflect on the pattern itself, which I have previously identified as common to certain problems. I may say I understand the pattern when, for example, I have constructed a model of this pattern, identified the basic elements of it. Then I may be able to formulate problems that follow this pattern and not only to recognize among some given problems those that satisfy the pattern.

Let us take, for example, the following problem: Luc has $1.45 more than Michel. Luc doubles his amount of money and Michel increases his by $3.50. Now Luc has $0.40 less than Michel. What were the initial amounts of Luc and Michel?

Understanding the problem as having a certain pattern may consist in perceiving a similarity between this and other problems done in class. This may allow the use of an analogous procedure to solve the problem. Understanding the pattern itself would probably involve a generalization of the problem, introduction of variables in place of all the givens and unknowns: four unknown states A, B, C, D are related by given relations r, s, t, u between A and B, B and C, C and D, D and A, respectively; to find A and B. Such understanding could be supported by a representation of the pattern in form of a diagram, like the one shown in Figure 1.

A pattern of solution would then easily be seen: given are the relations: A = r(B) = B + 1.45; D = u(A) = 2*A; C = s(B) = B + 3.50; D = t(C) = C – 0.40, whence D = u(A) = t(C), and thus u(r(B)) = t(s(B)) which can be solved as an equation in a single unknown: 2*(B + 1.45) = (B + 3.50) – 0.40 (Bednarz et al., 1992).

A similar ambiguity may occur with respect to ‘understanding a concept’. If the concept is thought of as a certain ready made, existing theoretical ‘object’ out there, named, defined or described in some way, related to other concepts and interpreted in various situations etc., then understanding it would consist in analyzing this definition or this description, recognizing these relations and these interpretations. The ready made concept would then constitute the object of understanding, i.e., that which is being understood.

But the phrase ‘to understand the concept C’ can be interpreted also in such a way that something is being understood on the basis of this very concept: something is being brought together as representing a concept, it is generalized and synthesized into that concept C. The concept would then be only formed in the act or process of understanding a situation. Such are the acts of ‘thematization’ Piaget speaks about; for example, the thematization of the use of geometric transformations into a concept that is fundamental for geometry, allowing the classification of its various domains as ‘theories of invariants’ of transformation groups.

In the former case the understanding would consist in finding out what ‘stands under’ the given concept C. In the latter, some situations would be ‘taken together’ — ‘une situation serait com-prise’ in form of a concept.

Thus, when it is said in ordinary language that a certain person has understood something, an X, it may mean that X is indeed the object of his or her understanding, or that he or she has understood something else of which X is seen as forming the ‘essence’ or the most important feature: he or she has understood something else ‘on the basis’ of X. The use of the expression ‘he or she has understood X’ in the vernacular may be confusing in this respect. When discussing the notion of ‘act of understanding’ in the next chapter the distinction between the object of understanding and the basis of understanding is very much stressed. It seems important to be aware of the difference between ‘what is to be understood’ and ‘on what basis something has to be understood’ or ‘how do we want something to be understood’ in, for example, designing a teaching sequence.

In his article, Greeno used the expression: ‘to understand the meaning (of X)’. The definite article ‘the’ suggests that X has a well determined meaning and what is there to understand is this pre-existing meaning. But in understanding we very often only just construct a meaning of X; then this meaning is a basis of our understanding of X. Dewey considered expressions ‘to understand’ and ‘to grasp the meaning’ as synonymous (Dewey, 1971, p. 137). He was thus explaining ‘understanding’ by ‘meaning’. We shall take an alternative point of view and, following Ajdukiewicz, we shall explain ‘meaning’ by ‘understanding’. A meaning of X will be, for us, a certain ‘way of understanding’ X, an abstraction from the occasional features of an act of understanding and retainment of only certain characteristics of it.

What Our Understanding Consists of? Different Ways of Understanding

Things can be understood in various ways and the understanding may consist of a variety of things. Mathematical examples of different ways of understanding are easily available from research on students difficulties in understanding mathematical notions. Here are some common students’ understandings of the limit of function at a point, as described by Williams (1991):

A limit describes how a function moves as x moves toward a certain point.

A limit is a number past which a function cannot go.

A limit is a number or point the function gets close to but never reaches.

In all three cases the understanding consists in identifying a certain characteristic property of the object of understanding (the concept of limit, of function, or just the term ‘limit of function at a point’).

Understanding may consist of a variety of other things as well. If the object of understanding is a phenomenon then its understanding may consist in finding an explanation of why the phenomenon occurs. One can also understand a practical action by being aware of why this action produces an expected result. There can be many kinds of explanations and therefore different ways of understanding. A person may feel she understands an action because she knows how to perform it successfully. A phenomenon can be understood by recognizing its main components and the relations between them. An understanding of a thunderstorm may consist of an explanation by the laws of physics (electrical discharges, laws of propagation of acoustic and light waves, etc.) or in an identification of a thunderstorm’s normal course, effects (rain, thunder and lightning, and the delay between them), states of the atmosphere before and after the storm etc.

Quite a lot of understanding is related to this question ‘why’ and consists in finding the ‘premisses’, ‘reasons’ or a ‘cause’ for something. Kotarbinski uses the following example: ‘Jan understood why the selling of the property was a mistake.’ He interprets it as follows: ‘this means that, through some kind of reasoning Jan has come to the conclusion that the selling of the property was a mistake for such and such reason.’ Thus an act of understanding can be a result of some reasoning — reasoning may lead to understanding something.

For some authors, ‘understanding’ is synonymous to ‘understanding why’. It is in this sense that Piaget uses this word in his book on Success and understanding (1978). He speaks of understanding a practical action (e.g., building a house of cards or putting a set of dominoes in a row so that pushing the first one would make all the others fall down); in this context, to understand an action means to understand why it works (leads to success) or why it does not work. In fact, Piaget is very demanding with respect to understanding. ‘Understanding how’ to make something, how to perform a practical action, what to do to attain a certain result, is not understanding at all. Understanding, for him, belongs to the realm of reason: it must be based on conceptualizations and such connections between these conceptualizations that are implicative and not causal. Understanding focuses neither on the goals that the action is expected to attain, nor on the means that can be used to reach them; it goes beyond the information given and aims at the ‘determination of the reasons without which successes remain mere facts without signification’ (ibidem, p. 222). Earlier in the book, in the introduction to the final conclusions, Piaget uses the terms of ‘notional comprehension’ and ‘explicative and implicative processes of comprehension’ (ibidem, p. 213). Piaget does not speak of any understanding but specifically of an understanding based on such conceptualizations that allow to explain why a certain action has been successful and to imply why certain possible actions would be or would not be successful. For us here, ‘understanding’ will not a priori mean such ‘notional’ or ‘reasoned’ understanding. We shall not impose other norms on an act of understanding except such as we subjectively feel necessary for a mental experience to be called this name.

What an understanding of other peoples’ behaviour and products of this behaviour, for example, live speech or written texts, consists of, has been a long-standing problem in hermeneutics and philosophy. For some philosophers (like Dilthey), understanding in this context meant empathy — feeling and thinking as the author feels and thinks. Others, (like Ricœur, 1976), proposed that a text, or any discourse for that matter, distances itself from the author, acquires a meaning of its own and the reader has to reconstruct this meaning for himself.

What ‘Stands Under’ Understanding?

Several pieces of information are needed to make a statement about an act of understanding less ambiguous. One should know what is the ‘object of understanding’, i.e., what is being understood; and on what basis is this object being understood (a reason?, an explanation?, a know-how? empathy?), as well as what are the operations of the mind that are involved in the act of understanding.

In asking a person whose intention it is to understand something what does his or her understanding of this something consist of, the expected reply is normally a description of that on which his or her understanding is based and of the operation of mind he or she has been using to make the link between this basis and the object of his or her understanding (for example, the person has identified the reasons of a certain action).

There seems to be a large variety of theoretical views on what can actually constitute a basis for understanding. Understanding expressions was traditionally regarded as based on either images or imagined feelings, situations, etc. or conceptual representations (Ajdukiewicz, 1974). Jerome S. Bruner (1973) based understanding of concepts on three kinds of mental representations: those that could be mediated through actions (enactive representations), those that could be mediated through pictures (iconic representations) and those that could be mediated through symbols or language (symbolic representations). Cognitive scientists preferred to think that understanding of any kind of discourse consists in retrieval from memory of mental ‘frames’, ‘scripts’, or ‘schemas’ which function very much like procedures in a software (Minsky, 1975; Davis, 1984).

A style of speaking (or maybe even thinking) that has gained some popularity in the past few years is embedded in the ‘environmental’ or ‘ecological’ metaphor. Concepts, it is said, cannot be thought of in isolation from whole domains of concepts, facts and procedures in which they have their meaning and which constitute, so to say, their ‘natural environment’. Therefore, it is impossible to speak of understanding of a concept without speaking at the same time of the understanding and knowledge of its environment — its conceptual domain. Coming to know a conceptual domain thus resembles ‘knowing one’s way around in an environment … and knowing how to use its resources as well as being able to find and use those resources for understanding and reasoning. Knowing includes interaction with the environment in its own terms — exploring the territory, appreciating its scenery and understanding how its various components interact’(Greeno, ibidem, p. 175).

In physical environments, understanding and reasoning is based on building the so-called ‘mental models’ of the reality a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Preface by Series Editor

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Understanding and Meaning

- Chapter 2: Components and Conditions of an Act of Understanding

- Chapter 3: Processes of Understanding

- Chapter 4: Good Understanding

- Chapter 5: Developmental and Cultural Contraints of Understanding

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding in Mathematics by Anna Sierpinska in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.