![]()

1

‘White Shamans’

Sources for Neo-Shamanisms

fastest growing business in america

is shame men shame women

you could have a sweat same as you took manhattan

you could initiate people same as into the elks

with a bit of light around your head

and some ‘Indian’ jewelry from hong kong

why you’re all set

(Extract from the poem Shame On [say it aloud] by Chrystos, published in the activist anthropological journal Cultural Survival Quarterly, Fall 1992: 71)

[T]hese new practitioners are not ‘playing indian’ but going to the same revelatory sources that tribal shamans have traveled to from time immemorial. They are not pretending to be shamans; if they get shamanic results for themselves and others in this work, they are indeed the real thing.

(Harner 1990 [1980]: xiv)

Western fascinations with shamanisms have endured from at least the seventeenth century to the present day (Flaherty 1988, 1989, 1992; Eilberg-Schwartz 1989). And while shamans were once deemed to be aberrant – ‘the shaman: a villain of a magician who calls demons’ (Petrovich 2001 [1672]: 18), ‘shamans deserve perpetual labor for their hocus-pocus’ (Gmelin 2001 [1751]: 27), ‘shamans are impostors who claim they consult with the devil – and who are sometimes close to the mark’ (Diderot et al. 2001 [1765]: 32) – they are now perceived by neo-Shamans as inherently ‘spiritual’ and in some way more ‘in touch’ with themselves and the world around them than modern Westerners, providing ‘a way back to greater balance with nature’ (Rutherford 1996: 2). The West’s reception of shamanisms is intertwined with the emergence of neo-Shamanisms: various people over the last four centuries, fascinated by the apparently bizarre antics of shamans, enthusiastically romanticised this so-called ‘savage’ into a pristine religious specialist. Some people also directly associated themselves with these practices – sometimes naming themselves ‘a shaman’ – so radically different from and exotic to Western attitudes and aesthetics, and became neo-Shamans. Such figures, who received literature, resources and imaginative accounts of shamans and/or other ‘savages’, might include the antiquarians John Dee (1527–1608) and his assistant Edward Kelley, Enochian Magicians (e.g. French 1972), and William Stukeley (1687–1765) a.k.a. ‘Archdruid Chyndonax’ (Sebastion 1990: 97–98; see also Piggott 1989; Trigger 1989; Green 1997; L. Jones 1998). Also, some time later, the early ethnographer Lewis Henry Morgan, who in the mid-nineteenth century began a search for ‘authentic America’ in which ‘playing Indian’ was an integral part, consisting of men’s secret societies in which participants wore Indian clothes, took Indian names and claimed guidance from Indian ‘spirit guides’ and ‘visions’ (P.J. Deloria 1998: 79). In true colonial fashion, inventing American identity required distancing real Indians, perceiving them to be already extinct or at least vanishing, to uphold an imperialist and romanticised idea of Indians past. The very real Native American struggle with social injustice and genocide was ignored. ‘New ethnographers’ thereafter continued to play Indian, such as Frank Hamilton Cushing, the famous ethnographer of the Zunis who enthusiastically embraced a ‘white Indian’ identity. He wore Zuni clothes and decorated his New York home in replica of a Pueblo Kiva (Deloria 1998: 119). Indeed, to ‘study’ the Zunis, Cushing had to ‘be adopted, he had to be made into a Zuni, and this required that he undergo the same social and ritual procedures which all Zunis underwent’ (Roscoe 1991: 127). Perhaps only following this process was Cushing, as a ‘white’ or ‘neo-’ shaman, fully able to write his ‘Remarks on Shamanism’ (1897).

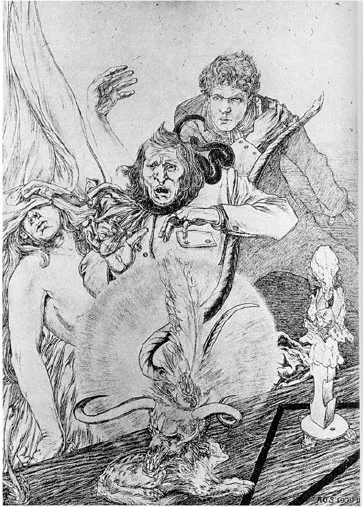

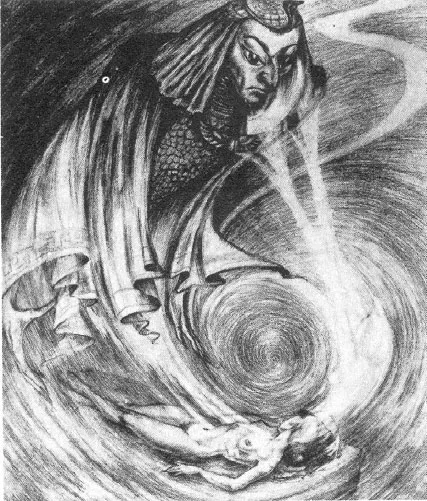

Neo-Shamans of the twentieth century include, I contend, a variety of artists and occultists. Greenwood (2000), similarly, draws attention to the influence of ‘shamanism’ on the practices of modern magicians, and Tingay (2000: 38) notes the influence of ‘shamanism’ on Madame Blavatsky, the mother of theosophy. Other individuals worthy of mention include the occultist Austin Osman Spare (1887–1956), whose idiosyncratic system of ‘atavistic resurgence’ (Spare 1993) incorporated sexual excitation and orgasm combined with ‘will’ and ‘image’ in a technique of ‘ecstasy’. ‘Spirit familiars’ (well known to shamans) were encountered, ‘automatic’ or trance drawings of them made (Figure 1.1), and the Native American spirit ‘Black Eagle’ was a major source of Spare’s ecstatic inspiration (e.g. Grant 1973, 1975, 1980, 1991 [1972]; Grant and Grant 1998). Similar shamanic other than human helpers are evident in the artwork of Australian witch Rosaleen Norton (1917–1979) (Figure 1.2) (Drury 1993). The poet Jerome Rothenberg, more recently, claimed that various romantic and visionary poets, including Rainer Maria Rilke, Arthur Rimbaud and the Dadaists, all represented ‘neoshamanisms’ (Flaherty 1992: 4; see also Rothenberg 1985). Modern artists such as Marc Chagall (1887–1985) and Vasily Kandinsky (1866–1944) were also neo-Shamans, with occultism, mysticism and folklore influencing their work. Kandinsky regarded the artist as a shaman (Rosenthal 1997: 20–21), as, more recently and famously, did Joseph Beuys (1921–1986). Tate Modern’s tribute to Beuys (part of the ‘Bits and Pieces’ collection display in the Landscape/Matter/Environment gallery) states he ‘was no ordinary sculptor. He was also a shaman’, and Beuys himself claimed ‘everybody is an artist’. Reflecting on these two comments, I have wondered whether Beuys also thought ‘everybody is a shaman’. Caroline Tisdall, Beuys’s biographer (Tisdall 1979), agreed the link is appropriate (pers. com.).

Figure 1.1 The Self in Ecstasy (1913) by occultist and trance artist Austin Osman Spare

Source: Courtesy of Kenneth Grant.

Figure 1.2 Nightmare by Rosaleen Norton, ‘a clear indication of the artist’s trance technique’ (Drury 1993: 27)

Source: Courtesy of Mandrake of Oxford.

Beuys has been termed a ‘shaman’ for a number of reasons. He was rescued by Tartars after the Stucka plane in which he was radio operator crashed in the inhospitable conditions of the Crimea during the Second World War. The Tartars revived him, badly burnt and freezing, with fat and felt insulation, and these substances became a primary inspiration for his work; he wrapped himself in felt for hours at a time, for instance, and wore a felt trilby hat he termed ‘shamanic’ during the performance of Coyote. He viewed felt and fat as alchemical substances, felt being both an insulator and a filter, and fat being an insulator with a unique state which fluctuates between solid and liquid. Beuys regarded the plane crash as an initiatory-like experience, likened it to a death and rebirth, and also endured a long-lasting breakdown which he viewed as a rite of passage essential to being an artist. Beuys’s words ‘show your wound’ espoused the view that vulnerability is the secret to being an artist, the term wound here perhaps alluding to the indigenous shaman as a ‘wounded healer’. Many of Beuys’s paintings are entitled Shaman, and the techniques he employed to produce the drawings entitled Coyote, as well as the performance of Coyote (New York 1974) itself (see Tisdall 1976, 1998), were certainly mimetic of shamanistic consciousness-altering practices: wrapped in an enormous piece of felt, wearing the trilby and ‘sulphur [another alchemical substance] boots’, and wielding a cane walking stick which he perceived as a ‘conductor’, Beuys spent three days in a room caged with a live coyote, accompanied by a tape-recording of chaotic turbine sounds. The question was ‘who was caged?’, and in performance dialogue with the animal, the coyote took over, urinating and defecating on the Wall Street Journal – which Beuys deployed as a statement against capitalism (Beuys was a candidate for the Green Party but became disillusioned by it).

Of interest to a study of alternative approaches to archaeology and shamanisms, one of Beuys’s ‘Bits and Pieces’ exhibits is entitled Tramstop Archaeology (1976), various entheogens including magic mushrooms and Datura are integral fabrics in some of these pieces, and finds of bog bodies are known to have inspired Beuys’s sculptural works. Further, Beuys defined the spiral (organic or implosive), split-cell and diamond (crystalline or explosive) shapes from the Neolithic passage tomb art of Newgrange (Boyne Valley, Ireland) as ‘The Three Energies of Newgrange’, inferring that the ‘ancient Celts [sic] had a sophisticated knowledge of physical and spiritual energies’ (Tisdall 1998: 72). According to one artist (‘Ricky’) speaking at Tisdall’s celebration of Beuys’s ‘Bits and Pieces’ works (an open event at Tate Modern entitled ‘Shamanism and Healing’), his obsession with the red stag (also the elk, both of which Beuys perceived as ‘spiritual’ and figure strongly in his art) ‘brings us back to Alta Mira’; further, ‘he was a Celt, he was a shaman’, and Tisdall suggests the megalithic The End of the 20th Century (1983–1985) makes reference to Stonehenge. Art, archaeology and shamanism are, I think, united in Beuys’s works which explicitly challenge the elitist dealer-critic system: in Beuys’s world-view, archaeology, the everyday (in a similar vein to Duchamp’s readymades) and shamanism – particularly healing (of nature, individual, society and planet) – are embraced by the term ‘art’. So, as had happened in previous centuries, the shaman/neo-Shaman in the twentieth century was relegated to the realm of the bohemian artist (e.g. Tucker 1992). In all, shamanisms and neo-Shamanisms have, without doubt, deeply permeated new religious movements and other aspects of society, such as art, in the modern era.

Neo-Shamans re-emerged in the academy when anthropologists, following an interlude of Boasian ‘scientific’ methodology, again went ‘native’ and trained as shamans during the 1960s, and psychologists experimented on the entheogenic substances some shamans consumed, such as the chemical derivative LSD (e.g. Grof 1996 [1975]). Many such anthropologist researchers, in South America particularly, participated in entheogenorientated rituals which enabled first-hand encounters with shamanic realities. Examples of these neo-Shaman ‘anthros’ include Michael Harner (1990 [1980]), Carlos Castaneda (arguably not an anthropologist, see below) and Douglas Sharon (1978), who, following initiation into the traditional shamanic practices they were studying, brought shamanisms to the West – and/or took neo-Shamans to the host culture – for spiritual consumption. These events neatly coincided with the widespread use of LSD and other entheogens, and emergence of a counter-culture in search of alternative life-ways and spiritual fulfilment. Aldous Huxley’s (1959) experiments with mescaline (chemically linked with LSD), in particular, inspired them to explore shamanic realms, and Timothy Leary, the controversial ‘godfather of acid’, encouraged them to adopt an alternative lifestyle with the mantra ‘tune in, turn on, drop out’. These neo-Shamans of the 1960s and 1970s enthusiastically consumed popular anthropology books on shamanisms (such as Castaneda 1968; Furst 1972; Harner 1972, 1973a). Following this historical trajectory, the closing decade of the twentieth century and early years of the twenty-first witness growing reproduction and reification of neo-Shamanisms with increasing numbers of people employing aspects of shamanisms in their occupations and turning to ‘shamanism’ as a path for personal and communal empowerment.

Characterising neo-Shamanisms is a complex endeavour (e.g. Hess 1993) and a variety of potentially useful terms fail to embrace its diversity sufficiently. Terms such as ‘crisis cults’ are inappropriate since while neo-Shamanisms may express a crisis in Western religious thinking, related to the ‘crisis of modernity’ (Lyon 1993), they have no leader or organisation that warrants the term ‘cult’. ‘Revitalisation movements’, or ‘marginal religious movements’ (Wilson 1974: 596–627) better reflect the situation, although neo-Shamanisms are too fragmented to be simply a movement, and only some neo-Shamanic groups such as road protestors (e.g. Letcher 2001) readily lend themselves to Maffesoli’s (1996) post-modernising of the term ‘tribe’. Lindquist (1997) argues ‘neo-shamanism’ is a ‘subculture’, but I think practitioners are rarely socially ‘deviant’ in the sense that this term may imply: neo-Shamanisms are increasingly becoming less marginalised and more integrated into society, and thus cannot be characterised as counter-cultural (as described by Roszack 1970). But just as neo-Shamanisms are not simply counter-cultural, so they are not simply ‘New Age’ (Lewis and Melton 1992). Where New Agers ‘honour spirit above matter’ (Harvey 1997b: 122), the Pagan element in neo-Shamanisms suggests a spirituality which is often earth-orientated. Indeed, neo-Shamans and Pagans often use New Age as a derogatory term, denoting a shallow, woolly approach to spirituality (see also Pearson 1998; Shallcrass 1998: 168), with one Pagan suggesting ‘newage’ be pronounced ‘rather unkindly, as in “sewage”’ (Fleming n.d.b).

With often highly pluralised beliefs and practices, neo-Shamans are influenced ‘arguably’ by a syncretism of reactionary thought and post-modernism, although describing neo-Shamanisms in terms of ‘modern’, ‘post-modern’, etc. is rather academic and artificial: most neo-Shamans and others in society are unfamiliar with, or at least not interested in, these terms; they are simply living their lives. This does not negate their use however, since such terms allow academics to appreciate the socio-political locations of neo-Shamanisms within their own intellectual framework, and such labels also need not deny social agency and individual sensibilities. At their most modern, individualistic and conservative, neo-Shamans teach business executives how to contact ‘spirit guides’ which can help them make more money (though that might be too harsh a criticism of Heather Campbell’s workshops, also author of Sacred Business [Firth and Campbell 1997], who conducts neo-Shamanic workshops for business managers). Western capitalism has influenced them in their ‘sacralization of the self’ and fostering of ‘New Age capitalism’ (Heelas 1992). But where some live happily as business people in a capitalist marketplace, others destabilise the fabric of modernism. At their most post-modern, neo-Shamans execute dissonant acts which render conventional metanarratives of gender defunct (see Conclusion). Neo-Shamanisms may thereby embody a number of socio-political locations, including counter-cultural, being socially integrated, modern and post-modern. In this diversity, neo-Shamanisms reject attempts at simplistic classification (following comments by Heelas 1993 and Lyon 1993 on New Age). Terming neo-Shamanisms ‘counter-cultures’, ‘subcultures’ (Lindquist 1997) and ‘movements’ seems to miss the point; we might rather speak less pejoratively, plurally and simply, of ‘neo-Shamanisms’.

‘Indigenous’ critics have used the terms ‘whiteshamanism’ (Rose 1992) and ‘plastic medicinemen’ (Churchill 1992) to describe Westerners ‘appropriating’ their traditions. ‘Neo-shamanism’, coined by Rothenberg (e.g. 1985), has become a widely used academic term for this cultural interaction, although ‘modern shamanism’, ‘new shamanism’, ‘urban shamanism’ and ‘contemporary shamanism’ are also widely used. ‘Neo-Shamanisms’ may be a more appropriate, sensitive and critical orthography: (1) it distinguishes ‘Western’ forms from those in ‘indigenous’ communities, where ‘modern’, ‘urban’ and ‘contemporary’ may not; (2) pluralising, cumbersome though it may be, embraces diversity and difference, rather than generalities and meta-narrative;1 (3) capitalisation locates, rather than downsizes neo-Shamanisms alongside established ‘religions’ such as Christianity, and is sensitive to neo-Shamans themselves, reflecting both freedom of expression and the diversity of practitioners who may respond with exasperation to ethnographic labels (e.g. Høst 2001); (4) the lower case ‘neo-’ prefix (also in ‘shamanisms’ when referring to ‘indigenous’ practices) suggests the terms ‘shamanisms’ and ‘neo-Shamanisms’ are Western inventions, and avoids pinning down, in metanarrative, a variety of practices (both neo-Shamanic and shamanic) to a fixed and named type; and (5) while theism does not indicate ‘an organised system … a reification constructed from disparate lifeways’ (Harvey forthcoming), but rather a suffix which acknowledges similarities, so the prefix neo- does not denote inauthenticity, like quasi- (I hope it is not too reminiscent of other neo-s such as Neo-Nazi, as has been suggested to me). Indeed, while it may be useful to contrast shamanisms with neo-Shamanisms, the diversity and sometimes permeability of both suggest a sharp distinction is misleading. And here I must enter a debate on the issue of authenticity and validity with the inevitable, if simplistic and I think naïve, question ‘are neo-Shamans shamans?’.

When responding to this question, the term ‘shaman’ can arguably be seen as self-defining: essentially, people calling themselves shamans are shamans since the term is invented and means different things to different people. Such relativism would, however, ignore the reality of situations where neo-Shamanic approaches to shamans are blatantly neo-colonialist. It would also run the risk of suggesting neo-Shamans are the same as shamans; in most cases, particularly in instances of neo-colonialism, they most certainly are not. But not all neo-Shamans are neo-colonialist and, in recognising this diversity, I think it is possible to differentiate some neo-Shamans who are more like indigenous shamans or make constructive contributions to them from those who are not (see following chapters). But in some cases a distinction between shamans and neo-Shamans is misleading. Where shamanisms are being urbanised, such as in Peru (e.g. Press 1971; Joralemon and Sharon 1993) and Buryatia (Humphrey 1999), or being taught by Michael Harner and other core-shamanists such as among the Sami and Inuit (see, for example, Hoppál 1996; Khazanov 1996; Townsend 1999), dichotomous terms neglect the dissonant, unpredictable and nuanced reality (see especially Chapter 7).

Critics of neo-Shamanisms tend to fall into a methodological trap of comparing neo-Shamanisms with indigenous shamanisms, when, as I have stated, the plurality of both, and their engagements, indicate they may or may not be commensurable. In simplistic terms critics, then, logically, move on to pose the question ‘is neo-shamanism authentic, or valid?’, with responses most often in the negative. There is certainly a snobbish and derisive tone in much literature on neo-Shamanisms: real shamans are perceived to be culturally distant and Other, and therefore ‘authentic’; neo-Shamans are invented, deluded and specious. In one sense this shamanism vs neo-Shamanism dichotomy might arguably reify a primitivist or noble savage stereotype of indigenous peoples. At the very least it is shamanophobic and reveals a hypocritical attitude taken by those anthropologists who suggest there is no such thing as ‘static’ tradition or culture, but who discriminate against neo-Shamans because they are not apparently part of a ‘tradition’ and appear, at least on the face of it, to be piecemeal spiritual consumers in the global village. In true logical fashion, the question ‘is neo-shamanism authentic, or valid?’ begs another question: ‘when does a new religious path or set of paths become traditional and authentic?’, or at least, a...