1 The nature of ecosystems

The biological world is one of great diversity and complexity. A systems approach is useful in helping us to understand the interactions between living organisms and their environment (which includes the biotic environment of other living creatures). The concept of the ecosystem provides a way in which the functioning of the biological world and its interactions with the physical environment can be understood. The ecosystem concept is useful in resource management and as a basis for predictive modelling. This chapter covers:

- Complexity of the biological world and its physical environment

- Development of the ecosystem concept

- System theory, ecology and ecosystems

- Abiotic and biotic environment of ecosystems

How this book approaches the complexity of the biological world and its environment

How can we make sense of the complex and constantly changing interactions between the living world, with its myriad species and individuals, and the multifaceted and dynamic environment which life inhabits? In this book we examine this basic question, starting from the idea of the ecosystem as the basic unit of living organisms in the environment. Understanding how ecosystems operate, and how they support the existence of groups of organisms, is not just a question of scientific interest. At a gathering pace since the 1940s, there has been increasing concern about harmful effects caused by human actions on the planet’s life support system. Although concerns were, at first, confined to a small group of scientists and environmental activists, it is now a global issue at the top of the international political agenda. Exactly what has occurred and what may happen in the future is not clear. However, most informed people agree that at best the consequences may be uncomfortable for humankind, and at worst may be catastrophic.

The ecosystem concept is fundamental to examination of human impacts on life on Earth. It provides a way of looking at the functional interactions between life and environment which helps us to understand the behaviour of ecological systems, and predict their response to human or natural environmental changes.

In this chapter we describe the evolution of the ecosystem concept, and its contemporary definitions. Many people have some idea of what is meant by the term ecosystem (see Definition Box).

Definition

Two definitions of the term ecosystem

- ‘An energy-driven complex of a community of organisms and its controlling environment’ (Billings 1978).

- ‘An ecosystem is a community of living organisms together with the physical processes that occur within an environment’ (Pullin 2002).

These two definitions, nearly 25 years apart, provide consistent statements on the key attributes of ecosystems. These key attributes are directly related to the concepts of functional ecology which are used in this book. In particular, interactions between the physical environment and organisms, and between organisms and other organisms direct the evolutionary trends of competition, tolerance of stress, and tolerance of disturbance. These interactions are central to the functional processes specified in the definitions of ecosystems.

Ecosystems can be analysed using the concepts of system theory. This approach provides definitions and general rules which allow very complex structures to be understood and predicted. When allied to mathematical modelling techniques, system theory provides the framework for a highly effective general approach to the study of ecosystems. We examine below some of the main issues in system theory, and relate these ideas to the ecosystem concept.

Ecosystems are found throughout the biosphere (Flanagan 1970). The biosphere is the zone in which life is located, in a shell around the planet. If abiotic environmental life support systems are included, this zone is sometimes referred to as the ecosphere. Within the ecosphere, ecosystems exist at spatial scales from a crack in a rock (see Chapter 5 for more on the endolithic ecosystems of Antarctica) to rainforest or oceanic ecosystems, covering areas of thousands of square kilometres (see Chapters 3 and 7). Sometimes the boundaries of ecosystems coincide with natural spatial features, such as an island or a type of vegetation, such as a forest. However, ecosystem boundaries may be defined by purely human criteria, such as a national or state boundary. Ecosystems may even be artificially constructed in the laboratory. Biomes are the largest-scale units which depict the global pattern of the distribution of vegetation in the biosphere. This pattern is generally related to current and recent climatic conditions, and contrasts with the pattern of zoogeographical realms, which relate to barriers to dispersal and to the outcomes of continental drift. As the most important element in any ecosystem is its vegetation, which provides the input of energy into the whole system, we examine the global patterns of biomes in more detail in Chapter 7, and relate these patterns to elements of functional ecology.

The biosphere extends from at least 0.5 km below the floor of the ocean into the atmosphere. Life has been detected up to 6.5 km above the Earth’s surface. This is close to the tropopause. Thus the biosphere is no more than 20 km thick, 0.3 per cent of the planetary radius. However, as far as we know, it is the home of all life (though see our speculation on the possibilities of life elsewhere in the Solar System in Chapters 3 and 5).

Ecosystem functioning is the main theme of this book. In Chapters 2, 3 and 4 we outline the functional interactions between energy and materials in ecosystems, and the way in which these support life in ecosystems. Understanding the operational and support functions of ecosystems (how they work and what they do) is vital to the use of the ecosystem concept for predictive purposes (for example, understanding the potential impacts of global warming: see Chapter 11). The energy and material subsystems are analysed individually in Chapters 3 and 4. In reality these are intimately interrelated in the operation of ecosystems. Most of the materials which are required to construct living organisms are in relatively short supply within the boundaries of the biosphere. Cycling of these materials by ecosystems is thus a critical part of the whole life support system of the planet.

Ecosystems interact in a variety of ways through their biotic and abiotic components. Chapter 5 analyses the general response of ecosystems to stresses imposed by different physical environments and human activities. Seasonal and other temporal changes in ecosystem characteristics are an important variable influencing the intensity and timing of environmental stress affecting ecosystems. Natural change is a normal feature of the functioning of the Earth’s environment. Sometimes the disturbance produced by such change can be massive in its effects, resulting in conditions unfavourable to all or most members of the pre-existing biological community. Extreme examples include the effects of a major meteorite strike (such as the ‘dinosaur killer’ thought to have been responsible for the mass Triassic extinction suggested by Gould as far back as 1980) or a major volcanic eruption (see Chapter 2 for an example). Much more common are the effects of disturbance caused by grazing organisms for producer species like plants. Some of the most important aspects of ecosystem response to disturbance are discussed in Chapter 6. But much of the functioning of ecosystems is shaped by response to interactions between the various biological populations which make up the community structure of ecosystems.

Functioning ecosystems always change through time. The dynamic nature of ecosystems operates over time scales ranging from daily to geological time. One of the most important dimensions of this interaction is competition between individual, and populations of, organisms. This is analysed in Chapter 7.

Change to ecosystems may be caused by human actions. One of the issues that give rise to the greatest concern among scientists concerned with the environment, and among the public at large, is the effects that humans are having upon ecosystems and their functioning. These human impacts act at various scales and with varying severity. Analysis of selected examples in Chapters 9 to 11 critically assess what effects human impacts may have, and how serious these threats are to ecosystem function. One of the most difficult problems facing environmental science is diagnosing the nature of environmental change. Not only is the extent and rate of change often hard to detect, and even harder to predict, but it may also be very difficult to distinguish between those components of change which are a part of natural environmental and ecosystem dynamics, and those which are a result of human impacts. Yet unravelling all of these issues is vital if ecosystem function is to be sustained, and irreparable damage to the biosphere avoided. These problems are discussed more fully in Chapters 9 to 11.

The ecosystem concept and the biological world

The ecosystem concept provides a convenient means of structuring and understanding the highly complex system which is our world. Even now a significant proportion of living organisms on this planet remains undiscovered and unclassified. It is likely that there are whole ecosystems which as yet remain unknown (especially in the oceans).

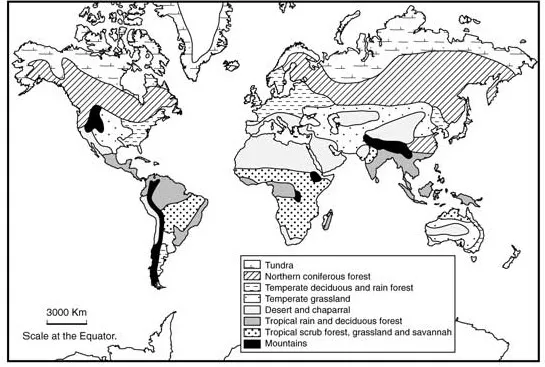

If the different kinds of organisms present a formidable array of forms and functions, this complexity is added to by the fact that, to a greater or lesser extent, each individual organism is different from all others of the same kind. Some living organisms do not conform to this rule by reproducing asexually, but individual distinctiveness is one of the keys to survival. An essential element of life is that species must exist in numbers sufficient in both time and space to be able to support breeding at a level which will replace individuals lost through death. These groups of individuals are called populations. Populations form the next step in the hierarchy of life after individuals. Groups of populations which occur together in defined locations form recognisable communities of species. Where these communities are adapted to similar combinations of types and intensities of environmental pressures (in one or more geographically distinct locations on the planet’s surface) they form functional groups of species. One or more functional groups of organisms (sometimes many), together with a defined set of abiotic environmental conditions, form an ecosystem. Groups of ecosystems which share broad environmental characteristics are termed biomes. Finally, the whole global assemblage of biomes comprises the biosphere. The hierarchy is shown in Box 1.1. The distribution of land biomes is shown in Figure 1.1. Chapter 8 considers the relationships between biomes and their abiotic environment in detail.

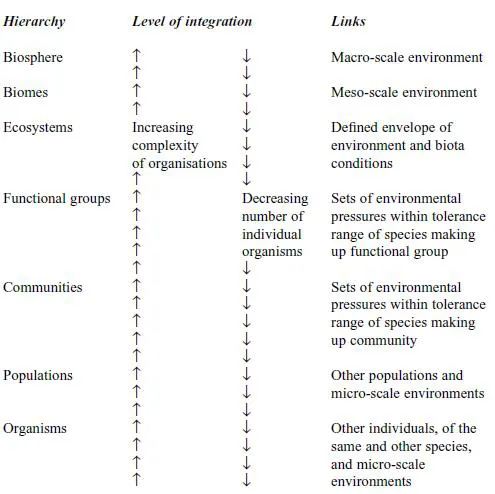

Box 1.1

Hierarchy of life: level of integration and links

To understand ecosystem functioning we must appreciate what each level of organisation involves, how it relates to levels above and below, and how the whole structure is integrated. At the level of the individual, an organism will grow and may reproduce. Its genetic characteristics can be transmitted from generation to generation, and through the process of natural selection will help to ensure the survival of the species. Over numerous generations this process may result in the evolution of a new species which has a specific ecological niche: its functional role with respect to its biotic and abiotic environment. The individual interacts directly with other individuals of the same and other species, through competition and predation. Any individual organism is also profoundly affected by its controlling abiotic environment. The population, comprising a number of individuals of the same species, contains a wider range of genetic information than any individual. The community is the aggregate of all biological populations in a defined area. Plant, microbial and animal communities are usually distinguished. Populations respond to the environment by adaptation, and all individuals within the population are in competition for resources to sustain life. Populations interact with other populations within communities to form functional groups, in response to biotic interactive pressures, such as consumption and competition for biological resources like water and light, and also to abiotic stress and disturbance pressures on survival and reproductive success.

Figure 1.1 Distribution of land biomes

One type of relationship which is of importance to the understanding of ecosystems is the trophic structure of the community (Figure 1.2). Trophic structure may be defined as the structure of energy transfer and loss between different populations in the community. Every population belongs to a particular trophic level. This is a statement of its position in the energy transfer structure of a particular community. This is important in understanding ecosystem function, and trophic structure is characteristic in many general types of ecosystems, such as lakes or deciduous forests (Odum 1971). Trophic levels and trophic structure are explained more fully in Chapter 3.

Environment of the biological world

The abiotic environment, often termed the physical environment, consists of a series of complex, interactive energy-driven systems. Those with which we are concerned function in the biosphere. This term was first used by the Russian mineralogist V.I. Vernadsky (1863–1945) as a means of providing a holistic view of nature, including the abiotic environment. It is by no means coincidental that this concept first emerged in Russia, immediately following the Bolshevik Revolution, when perspectives integrating life, including human activities, with the physical environment, were fashionable (Bowler 1992). The systems of the physical environment are influenced, and in some cases controlled by events and factors which lie beyond the biosphere, but these issues are beyond the scope of this book. Readers requiring further information on physical environmental processes are referred to other titles in this series.

Figure 1.2 Trophic structure and energy flow in an ecosystem