- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Race and Ethnicity: The Basics

About this book

Race and ethnicity have shaped the social, cultural and political character of much of the world, and remain an important influence on contemporary life in the 21st Century. Race and Ethnicity: The Basics is an accessible introduction to these potent forces. Topics covered include:

- The forms and dynamics of racial and ethnic relations

- The dynamics of inequality

- The relationship between prejudice and discrimination

- Ethnic conflict

- Models of inclusion

Including plenty of examples, chapter summaries and a glossary, this book is an essential read for all those interested in the contested field of race and ethnicity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Race and Ethnicity: The Basics by Peter Kivisto,Paul R. Croll in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

DEFINING THE SUBJECT

Race and ethnicity have, during the centuries since the advent of the modern nation-state and the era of colonialism, profoundly shaped the social, cultural, economic, and political character of much of the globe. This includes both the wealthy nations of the world and the poor ones. Contrary to the predictions of modernization theorists and Marxists, both of which foresaw a future in which race and ethnicity would decline in significance as a consequence of the evolution of capitalist industrialization or the more overarching impact of the totality of modern institutions and practices, the historical record clearly reveals that divisions based on race and ethnicity remain a salient feature of contemporary social life in the twenty-first century.

Indeed, to categorize people in everyday conversations along the lines of racial or ethnic group affiliations is commonplace. Thus, in the US to speak of African Americans or blacks is to lump approximately 12 percent of the nation's population into one of the five prominently identified races in the nation. On the other hand, to speak about Swedish Americans or Italian Americans—equally commonplace—is to place millions of people into what are seen as the vast array of ethnic groups residing in the nation. A similar pattern can be seen in the UK, where the term “black” was used a few decades ago to describe the post-World War II immigrants coming largely from the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent, in this case the term black being used more broadly than in the US context. Over time, these two groups would be distinguished, respectively as Afro-Caribbeans and Asians. At the same time, the UK used the term ethnic or national group to refer to Scots and the Welsh, two groups with historic roots in the nation as deep as are those of the English.

In these examples of the way these two terms are used, there appears to be a distinction being made wherein race refers to biological or physiological differences, while ethnic refers to cultural differences. In practice, however, the two are often more interconnected, convoluted, and subject to historical change. Thus, Jews throughout Western Europe and North America were viewed in both racial and ethnic terms during the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth. However, after the Holocaust, a pronounced shift occurred in all of these nations that resulted in locating Jews racially in the same racial grouping as the majority population, which meant that they were considered to be white. At the same time, they were defined as being a distinctive ethnic group within that racial category.

To complicate matters further, in some societies people are placed into categories in an either/or fashion. One is either white or black. Nowhere was this more evident than in the US for much of its history, where what became known as the “one-drop” rule prevailed. What this rule meant was that any person with the slightest amount of black ancestry would be considered black. In one illustration of this phenomenon, a woman in Louisiana who was 1/32 black and thus 31/32s white sought to have her race listed as white on her driver's license. The state denied that request and prevailed in the courts. The consequence of this approach is that a public recognition of race mixing is repressed. It should be noted that the mixed race individual is defined as being a member of the subordinate group, not the dominant group. This is a mode of categorizing people based on what is termed “hypodescent.”

Of course, race and ethnicity would not be such controversial topics if all that was involved was categorization. But the history of the use of these terms reveals that to categorize is to place people in a hierarchy that defines groups in terms of whether they are to be favored or not, privileged or not, empowered or not, economically advantaged or not, and so forth. Moreover, history also reveals that dividing people along racial and ethnic lines has generated forms of intra-group conflict, coercion, and violence, including in the most extreme forms of conflict attempts to exterminate an entire group. The genocidal campaigns that the world has witnessed during the past century, from the Armenian genocide after World War I to the ghastly attempt by the Nazi regime to destroy European Jewry, through to the campaign of extermination that Hutus undertook against the Tutsis in Rwanda and the ethnic cleansing in Bosnia that sought to kill off the territory's Muslim community reveal the continual threat of barbarism in the modern world.

If this was the whole story, it would clearly be best to do whatever can be done to eliminate or reduce as much as possible ethnic and racial definitions. However, these forms of identity have not simply been a source of conflict, but have often been a more positive source of personal identity and group affiliation, offering people a way to create a meaningful life. A shared history and culture can provide people with a source of strength that can help them meet various challenges collectively.

Given the Janus face of race and ethnicity and their continuing importance, the challenge is to better understand them in order to promote that which is positive while combating the negative. Sociology and anthropology, the closest of social science relatives, have from their respective origins paid considerable attention to race and ethnicity, and thus contemporary scholars build on a long and productive tradition of empirical research and theoretical development. Indeed, the sheer volume of published works in this field can quickly overwhelm the student novice. This book is conceived with this fact in mind. Its purpose, quite simply, is to acquaint students and other interested readers with the sociological subfield devoted to the social scientific understanding of the forms and dynamics of racial and ethnic relations. In this regard, one caveat at the outset is in order. While the issues discussed below are applicable in any and all national contexts, our examples will chiefly be drawn from major English-speaking industrial nations, which will be the places that most of our readers will be most familiar with.

Before turning to four substantive topics addressing respectively prejudice and discrimination, the dynamics of inequality, ethnic conflict, and modes of incorporation of ethnic and racial groups, we spend time in this chapter clarifying what exactly the subject matter at hand is, beginning with a look at the nature of the relationship between race and ethnicity.

HOW ARE RACE AND ETHNICITY RELATED?

There is at the moment a discussion about whether it's a mistake to talk about racial or ethnic groups (Brubaker 2004). The rub, according to those who have called this common practice into question is that two things tend to happen when we discuss ethnicity or race in terms of groups: groups are essentialized and they are viewed as homogeneous. To say they are essentialized means that groups are seen as fixed and determinate, and not subject to change over time. The concern about homogeneity points to the fact that to speak about a group can imply that it can be seen as referring to all members of the group without regard to internal differences. We understand the concerns of those who have advocated for a way of viewing ethnicity and race that takes us “beyond groupism” (Brubaker 2004: 11), but think that it is not only unlikely that people will abandon referring to groups, but unnecessary to do so since properly understood, such language is a convenient shorthand.

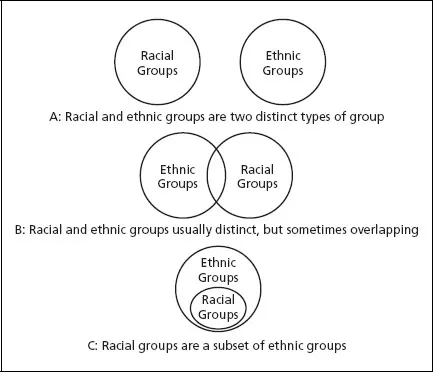

The question to be addressed in this section concerns the relationship between racial groups and ethnic groups. As Figure 1.1 illustrates, we will examine three different answers to the question. The first suggests that racial groups and ethnic groups are two different types of group. The second position claims that while racial and ethnic groups are usually distinct, in some circumstances they are overlapping. The third views racial groups as a subset of ethnic groups.

An immediate issue arises in any effort to decide which of these three perspectives is more persuasive. Are we interested in determining how ordinary people understand the relationship, or are we trying to make an assessment based on an analytical perspective useful for sociological inquiry? While both are reasonable ways of answering the question, we are concerned here with these terms as sociological concepts. That being said, it is often difficult for sociologists to neatly separate everyday usage from sociological concepts, due to the fact that the latter is derivative of and embedded in the former.

RACE AND THE COLONIAL LEGACY

Race was used far earlier than ethnicity in everyday discourse. The beginning of modern notions of race coincided with the European colonization of the world, at which time contact, conflict, and the oppression of people from the “New World” with different physical features and different cultures led to an ongoing debate about the human character of the “other.” European commentators, using their own civilization as a standard by which other civilizations would be judged, tended to find them wanting. Their ethnocentric perspective on the world sometimes led them to conclude that the “other” was not fully human. At other times, they distinguished their “civilized” world from that of the “barbarians.” It was the rare humanist who could see through this viewpoint. However, a minority opinion shared the enlightened perspective of the great sixteenth-century French essayist Michel de Montaigne, who in his essay “Of Cannibals” (written in response to seeing a cannibal brought to France by an explorer) wrote,

Figure 1.1: The relationship of racial groups to ethnic groups: competing conceptual models.

I think there is nothing barbarous and savage in that nation, from what I have been told, except that each man calls barbarism whatever is not his own practice; for indeed it seems we have no other test of truth and reason than the example and pattern of the opinions and customs of the country we live in

(Montaigne 1958: 152)

The ethnocentrism that Montaigne tried to challenge succeeded in shaping our understanding of race. The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus offered the first of numerous “scientific” efforts to classify the human population by breaking it into various races. Specifically, he divided humankind into four major racial groups: white, red, yellow and black. While this might at some level be seen as a reasonable broad generalization about differences in skin coloration, he meant it to be far more than a mere description of differences in physical appearance. In his view, the physical differences were deeply interconnected with differences in temperament, intelligence, and moral worthiness. Linnaeus assumed that racial differences could speak to determining who was capable of reason and who was not, who was morally responsible and who was not, who was fit for leadership and who was destined to be led, and who was understandably the conqueror and who was the conquered.

This sort of thinking characterized the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as witnessed in Comte Arthur de Gobineau's The Inequality of Human Races (1915[1853–1855]). Gobineau's work set the tone for a century of writing on race, where the goal was not only to classify people along racial lines, but to highlight the presumed superiority of some groups and the inferiority of others. He was especially interested in differentiating strong and weak groups, contending that because the strong exhibited a willingness to migrate, they would inevitably conquer the weak, and in the process bring to them the benefits of civilization. Billed as science, what Gobineau actually produced was an ideological defense of European colonialism.

Such thinking permeated Social Darwinian ideology, with its belief in societal evolution and emphasis on the survival of the fittest. It offered a critique of those seeking to launch some form of a welfare state, wherein all of the members of a society would be accorded as fundamental rights a certain bedrock standard of living. According to Social Darwinists, to do so would amount to undermining the overall health of the society by preventing its weak and unhealthy elements from being eliminated naturally. This political worldview painted a picture of incessant struggle and conflict, a world that was “red in tooth and claw.” Such a perspective could lead to the promotion of such draconian positions as the suggestion supported by Franklin Giddings, prominent American sociologist and officer in the Immigration Restriction League, to force poor immigrants into workhouses where they would be prevented from producing any more children. It also fit in well with the Eugenics movement, first advocated by Sir Francis Galton (half-cousin to Charles Darwin), that sought to employ genetics to improve the human race through selective breeding.

Racialist thinking divided the peoples occupying the European continent further into subsets of the white race, with a division between the Teutonic, Alpine, and Mediterranean that was developed by William Z. Ripley (1899) being one such prominent example. The purpose of making such distinctions was not simply to determine difference, but to rank those differences on a racial hierarchy. Ripley and his peers always placed the Teutonic race on the top of the hierarchy and the Mediterranean race on the bottom. Considerable energy was devoted to attempting to place various groups into these categories. In this task, some groups proved to be especially problematic, such as Jews and Lapps. The former seemed not to fit into any of the three races, while the latter was suspected of having ancient origins in Asia.

As historian Nell Irvin Painter (2010) has stressed, these and similar efforts aimed at creating classificatory schemes of racial categorization were never done in a disinterested attempt to depict human diversity. Rather, the project was always designed to advance the argument on behalf of the existence of racial hierarchies as permanent, biologically rooted features of human diversity. As such, the project's purpose was to determine standards for adjudicating racial superiority and inferiority along the lines of intelligence and moral character. As such, racialist thinking served as a powerful ideological tool justifying oppression and exploitation. It provided a rationalization for European colonialism, for slavery, and for the subjugation of indigenous peoples by the charter members of settler nations such as Australia, Canada, and the US.

WHEN DID ETHNICITY COME INTO VOGUE?

Werner Sollors (1986) has pointed out that the word ethnicity didn't come into common usage until the 1930s, which coincides with the rise of Nazi Germany, whose official ideologues embraced the sort of racialist thought we've been describing. As a way of distancing themselves from the racism inherent in racialist thinking, some scholars tried to implement an alternative language. Michael Banton (1987: xi) points to the case of two prominent anthropologists, Sir Julian Huxley and A. C. Haddon, who “criticized mistaken racial doctrines and proposed the use of ‘ethnic group’ in place of ‘race’ when discussing the social aspect, because the adjective ‘ethnic’ more clearly indicated a concern with social differences.”

Note what they were proposing. They did not necessarily want to discard the term “race,” but instead wanted to limit its use to the nonsocial, which one can assume meant the biological. Huxley and Haddon were not alone in turning to ethnicity. The prominent figures associated with the Chicago School of Sociology, especially W. I. Thomas and Robert E. Park, increasingly sought to distance themselves from biologically rooted explanations by employing accounts rooted in culture and social structure. By the publication of the landmark Yankee City studies in the 1940s, led by Chicago sociologist W. Lloyd Warner (1963), it was clear that ethnicity was in vogue. However, the more social scientists used the term, the more it entered everyday language. A few years after World War II ended, Everett C. Hughes (1971[1948]: 153) described the term “ethnic group” as a “colorless catch-all much used by anthropologists and sociologists,” going on to predict that as it was increasingly “taken up by a larger public,” scholars would have to seek yet another serviceable term.

RACE AND ETHNICITY

Six decades later, we haven't followed Hughes’ advice, but instead continue to debate the merits of race versus ethnicity and seek to sort out their relationship. With this brief historical excursus on origins of these two terms completed, we turn below to an assessment of the merits of each of the three competing positions.

RACE AND ETHNICITY AS DISTINCT

Perhaps the most influential scholars to make the case for distinguishing racial groups from ethnic groups are Michael Omi and Howard Winant, in Racial Formation in the United States (1994). In their view, ethnic groups should be used to refer to those groups of voluntary immigrants who left their homelands in various points in Europe for the US, while race is especially apt in discussing African Americans and Native Americans. The rationale for making this distinction is that these groups have had very different historical experiences. While voluntary immigrants from Europe often confronted prejudice and discrimination, they experienced nothing resembling the oppression and marginalization that...

Table of contents

- Front cover

- RACE AND ETHNICITY

- The Basics

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgementss

- 1 Defining the subject

- 2 Prejudice and discrimination

- 3 The dynamics of inequality

- 4 Ethnic conflict

- 5 Modes of incorporation

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- References

- Index