- 484 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Industrialized and Automated Building Systems presents a detailed and balanced evaluation of the benefits and drawbacks of industrialized building systems, and considers technological, managerial and economical aspects of industrialization, automation in the industrialized building process in production, construction and design, and information technologies in design, production and construction on site.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Industrialized and Automated Building Systems by Abraham Warszawski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Methods & Materials. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Industrialization and Automation in Building

1.1

Introduction

It is the basic tenet of this book that a radical improvement of productivity and quality in building construction can be attained only through intensive industrialization and automation of the building process. Recent innovations in the building process should be viewed in the general context of the technological progress of human society over time. In this respect Toffler [6] identifies three major technological “waves” which advanced human society over a period of ten millennia from the most primitive level to its present state. Although initially focusing on technological production processes, these waves were accompanied by deep social and economic changes.

The first wave, the establishment of agricultural civilization, consisted in the settling of formerly nomadic societies in permanent settlements. The population in these settlements could satisfy much better its basic needs by employing orderly agricultural techniques, and devote part of its effort toward improvement of living standards in terms of shelter and various consumption goods. One of the main results of this revolution was the erection of permanent buildings made from wood, stone, bricks, earth, and other indigenous materials for a population which formerly lived in tents or caves. Building as a distinctive craft, and later as several specialized crafts, also emerged from this development.

The second wave, industrial civilization, resulted from the development of machines propelled by artificial energy—first by steam and later by electricity and oil. The industrial revolution, which started at the beginning of the 18th century with the invention of the steam engine, enabled substitution of human effort by stronger, faster, and more precise machine work. It also enabled the introduction of efficient and wellcontrolled processes for production of various new materials and products. The considerable capital investment in machines and other industrial facilities which was necessary had to be justified by the creation of large factories, each with a large output of standardized products.

The industrial revolution affected the building sector in many ways. Perhaps its most important effects were the introduction of structural steel and reinforced concrete as main building materials in the second half of the 19th century, and later, in the 20th century, the industrialization of work on a building site, making the most of mechanized materials handling equipment and of large prefabricated building components. However, for reasons which will be discussed later in this chapter, the potential for industrialization on site was realized only to a limited extent.

The third wave, the information revolution, which started in the second part of the 20th century, draws from the use of computers for storing, processing, and transmitting information, and for automated control of industrialized processes. Computerized control makes production more efficient in terms of materials use.

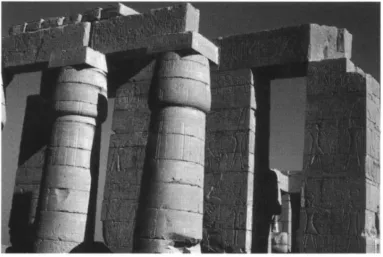

Figure 1.1 The Temple of Amon in Luxor

It also makes it feasible to cater by diversification to individual tastes, without significantly increasing the production cost.

The information revolution had a considerable effect on design work in building and on some aspects of its administration and control. Its effect on the construction process onsite is still very limited, mainly due to lack of a sufficient industrialized base.

The most important task of technological progress in building is therefore to increase the extent of industrialization onsite with a view to its subsequent automation, wherever feasible.

The industrialization of building is most effective when as many as possible of the building components are prefabricated in a plant with appropriate equipment and efficient technological and managerial methods. Comprehensive prefabricated elements that are produced in the plant considerably reduce both the amount of work onsite and dependence on the skill of available labor, on the weather, and on various local constraints.

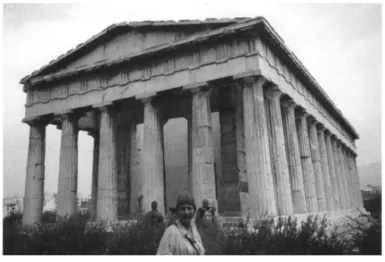

Production of large building components offsite is not a novel concept. Famous structures of the ancient world—in Egypt, Greece, and Italy (see Figs. 1.1 and 1.2)—were erected with prefabricated stone components such as pillars, slabs, and porticos, some of them weighing 5, 10, and even 100 tons. These components were sometimes hauled from quarries tens or hundreds of kilometers to their erection sites.

The transportation and erection of large components required, in the absence of machines, an enormous amount of human labor and superior organizational and logistic effort. It was therefore applied only in monumental buildings, such as temples and palaces, and justified by the architectural effect of volume, size and ornament obtained in this manner. The remaining mass of structures, mostly dwellings, were built with “conventional” methods that were much easier to execute. These methods used local materials—timber, clay, and stones often cut or molded into small work pieces such as bricks, blocks, and logs— which could conveniently be handled by one or two workers. The selection, adaptation, placement, jointing, and finishing of these pieces resulted in whole walls, floors, stairs, and other building segments. The efficiency and quality of this conventional process depended entirely on the skill of individual workers.

Application of prefabrication for other than architectural reasons—for example, economy, speed, or quality of construction—was made feasible with the general advent of mechanized production and transportation methods in the 19th century. Prefabricated components, mostly of timber and cast iron, were used in residential and public buildings. One of the most prominent examples of an advantageous use of the prefabrication potential was during the Crimean War in the years 1854–1855. Over a period of 2 months about 1400 barrack units were prefabricated in England, shipped to the war area (5000km away), and erected there to provide shelter for the English and French troops. Each unit was made of timber structure and walls and could house 20–25 soldiers. Another famous application was in the construction of the Crystal Palace in London. This large structure (90,000 m2) was assembled for the London exhibition in 1851 from a very large number of cast iron, modular skeleton and window components. In the second part of the 19th century several British manufacturing enterprises already specialized in the production of cast iron building elements—panels, gratings, stairs, balconies, columns, beams—and others which could be ordered from standard catalogues for various types of residential and public buildings. These and other early applications of prefabrication are described in Refs. [2–5, 8] and other sources.

Figure 1.2 The temple of Hephaestus in Athens

In the course of the 19th century, reinforced concrete established itself as one of the major building materials. It had some distinctive advantages over other prevalent materials: its main ingredients—sand, gravel, and water—were inexpensive and available almost anywhere. Its production process was relatively simple. It could be molded into any shape and with proper processing yield an attractive exterior surface. It was strong, durable, and resistant to weather, wetness, and various mechanical effects. For these reasons concrete components could compete successfully with stone, in monumental and architectural buildings, with timber and bricks in housing, and with steel in bridges and other heavily loaded structures. The use of high-strength prestressed concrete increased even further its range of applications. One of the first applications of precast concrete components was by W.H.Lascelles in England in 1878 [3]. Lascelles employed thin precast concrete plates attached to timber posts for use in walls and attached to concrete joists for use in floors of residential cottages.

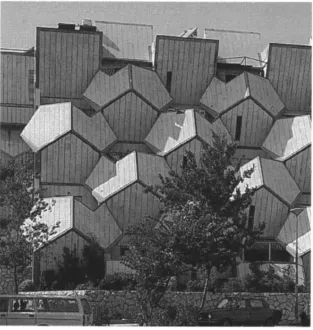

The full realization of precast concrete potential for prefabrication was made possible with the development of specially adapted transportation and erection equipment immediately after World War II. Only then did precast concrete establish itself as a viable alternative to the conventional building methods. The urgent demand for housing in the period following World War II and the active involvement of the public authorities in its supply created a very favorable environment for the proliferation of comprehensive prefabricated building systems. Such systems, consisting of prefabricated slabs, vertical structural elements, exterior walls, and partitions, stairs, and sanitary units, could offer a large output of building in a short time with reasonable quality. At the same time prefabrication also offered a wealth of architectural shapes and finishes—like those presented in Figs. 1.3–1.6— which could hardly be attained with any other technology.

Figure 1.3 The Marne la Vallée housing project near Paris (Bofil)

The demand for prefabricated building systems was at its peak in the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s in eastern Europe, where prefabrication became the predominant building technology, and also in many countries of western Europe where it was extensively used in the construction of new cities, new neighbourhoods near existing cities, and large public housing projects. The interest in concrete-based prefabrication methods also grew in the United States, which until that time was mainly involved in prefabrication of lightweight “mobile” houses. The U.S. government initiated, in the early 1970s, a largescale innovation project —Operation Breakthrough—in which it actively assisted in the development of a large number of building systems.

The demand for comprehensive prefabricated building systems subsided in the late 1970s, especially in western Europe and the United States (in eastern Europe it subsided with the political changes of the early 1990s), with the urgent need for mass housing in the urban areas largely satisfied. These systems found themselves at a disadvantage while competing with conventional building methods for small and diversified building projects. In the remaining large projects prefabrication was in hard competition with another mode of building industrialization—monolithic walls and slabs cast onsite in room-size steel molds. Prefabrication focused more and more on production of selected components— decorative exterior walls and prestressed modular slabs which were used mainly in public and industrial buildings.

The failure on the part of designers and producers to think in terms of systems rather than individual elements, and their failure to make system building more attractive and efficient given the present circumstances of fragmented and diversified demand, made prefabrication less competitive than existing methods. This initiated the vicious circle of lesser demand, hence a higher cost per unit, still less demand, and so on. The need for a system approach and its efficient management is expanded in the following sections of this chapter.

Figure 1.4 The Ramot project in Jerusalem (Heker)

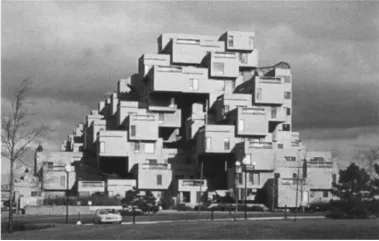

Figure 1.5 The Habitat project in Montreal (Safdie)

Furthermore, it is now possible to automate the industrialized building process with the aid of new information technologies. The use of computer tools in design and robots in production of elements gives the new methods a competitive edge in most building markets. This point will also be discussed.

Figure 1.6 The Conrad Hotel, Brussels (Decomo Co.)

1.2

The nature of industrialization

The industrial revolution marked the passage from a handicraft economy to one dominated by industry and machine manufacture. It originated with the introduction of machines, steam power, and new ways of making steel and iron in the 18th century. It received a tremendous boost in the late 19th century with the invention of electric power, the internal combustion machine, petroleum fuel, and chemical synthetics, and it culminates today with the advent of electronics, atomic power, and computers. Each of these stages increased productivity and improved the performance and quality of the product.

In this book we define an industrialization process as an investment in equipment, facilities, and technology with the purpose of increasing output, saving manual labor, and improving quality.

The following features are considered prerequisites to a successful industrialization process:

- Centralization of Production. Utilization of expensive equipment and facilities is feasible only with production performed at a single location (for a particular region). The process will thus use the Figure 1.6 The Conrad Hotel, Brussels (Decomo Co.) economies of scale with respect to capital investment, management, and auxiliary services. From this central location the product is shipped to the various consumer areas.

- Mass Production. The investment in equipment and facilities associated with an industrialization process can be justified economically only with a large production volume. Such volume allows a distribution of the fixed investment charge over a large number of product units without unduly inflating their ultimate cost.

- Standardization. Production resources can be used in the most efficient manner if the output is standardized. Then the production process, machinery, and workers’ training can best be adapted to the particular characteristics of the product.

- Specialization. Large volume and standardization allow a high degree of labor specialization within the production system. The process can be broken down into a large number of small homogeneous tasks. Workers continuously engaged in any of them can perform at the higher productivity level attained with specialization.

- Good Organization. Centralization of production, high volume, and specialization of work teams requires a sophisticated organization capable of a high quality of planning, coordination, and control functions with respect to production and distribution of the products.

- Integration. To ensure optimal results, a very high degree of coordination must exist between design, production, and marketing of the product. This can be ensured in the most efficient way within an integrated system in which all these functions are performed under a unified authority.

A high degree of industrialization, as characterized by these features, can be found today not only in the production of all types of consumer and capital goods but also in agriculture, medicine, education, and various types of service-industries.

The automation which computer control gives to many stages of production adds new dimensions to the industrialized process. Large production series, standardization, and specialization are no longer prerequisites for the feasibility of industrialization.

While large volumes of production are still essential to the feasibility of an investment, production no longer has to be uniform. There is a growing demand for a smaller series of diversified products which are better suited to the individual tastes of various customer groups and even of individual customers. If a company wants to survive in the competitive market it must cater to this type of diversified demand. Automation of production makes this feat possible at a minimum additional cost.

Automated features in both the design and the production of products make the proficiency of workers in execution of individual tasks less important. More sophisticated production tools and automated production control shift the emphasis from worker specialization in individual activities to their understanding of the whole process and its underlying technology.

1.3

Special features of the building process

After discussing the general attributes of an industrialized process, we proceed to examine their implications with reference to building systems. A building system was defined earlier as all work components necessary for a particular type of building together with their execution ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Conversion factors

- Chapter 1: Industrialization and Automation in Building

- Chapter 2: Building Systems and Components

- Chapter 3: Coordination Between Producer and Designer

- Chapter 4: Application of the Performance Approach

- Chapter 5: Production Technology

- Chapter 6: Prefabrication Plant

- Chapter 7: Production Planning and Control

- Chapter 8: Cost Estimating and Control

- Chapter 9: Quality Planning and Control

- Chapter 10: Economic Aspects of Industrialization

- Chapter 11: Long-Range Planning of Prefabrication

- Chapter 12: Automation in a Prefabrication Plant

- Chapter 13: The Robot Technology

- Chapter 14: Building Robotics

- Chapter 15: Building Robotics

- Chapter 16: New Trends and Developments