eBook - ePub

Improving Behaviour and Raising Self-Esteem in the Classroom

A Practical Guide to Using Transactional Analysis

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Improving Behaviour and Raising Self-Esteem in the Classroom

A Practical Guide to Using Transactional Analysis

About this book

This book will help all teachers who face challenging behavior in their classrooms. It offers support and guidance for dealing with issues of behavior and offers suggestions for building creative relationships in school. Through a combination of case study illustrations of key Transactional Analysis concepts, practical proformas, planning notes and resources that have been tried and tested with schools it will give you the confidence and skills necessary to develop effective classroom management.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Improving Behaviour and Raising Self-Esteem in the Classroom by Giles Barrow,Emma Bradshaw,Trudi Newton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

- What do you expect from this book?

- What do the authors of this book expect of you?

- What do the publishers expect of you the reader, and us the authors?

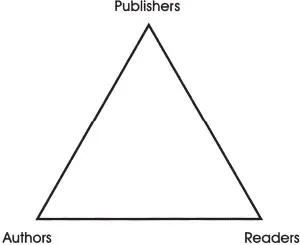

This book is about behaviour; in our view as authors behaviour is about communication between people in a context or environment. A major factor in our communication and relationship with others is how we contract with them, and whether we do this implicitly or explicitly. So this book is going to start with a contract (contracting will be dealt with in more detail in Chapter 3). However, we hope that by making this contract explicit it will be clear that the value of this book will be dependent on each party keeping their side of the contract. The reader will only get as much out of the book as they are prepared to apply, try out and understand its ideas. This can only happen if the authors and the publishers have done their part in making the book accessible and relevant.

It is also important to be clear about what each party can offer as well as expect.

- The authors have some information, concepts and ideas that they want to share with a broad audience.

- The publishers have a service to offer to readers. They have an organisation which is capable of delivering information to a broad audience.

- The readers have the potential to take, use and spread the concepts and ideas of the authors to affect the schools and pupils they work in and with.

Below is another way of looking at the questions or expectations given at the start of this chapter (Figure 1.1). Each side of the triangle represents two-way expectations.

Reader-Publisher expectations:

- The readers expect the publishers to provide up-to-date and relevant book titles of a high standard and professional quality. They also expect a range of titles to be produced on different topics — and behaviour is a topic that has been increasingly sought after by readers. They expect the book to be good value for money and to be readable. The publishers expect the readers to buy the book, to use it and to tell their friends about it. The publishers also expect to get paid for the production of books and to make a reasonable profit on each one sold.

Figure 1.1 The three-cornered contract

Author-Reader expectations:

- The authors expect the readers to use the book to help them to understand behaviour and self-esteem, then to use and apply the information to develop their skills and practice. The readers expect the authors to provide information in the book in a way that can be easily understood and applied to school life. They expect to get good value for money from the book and want it to provide information that they do not have already.

Author-Publisher expectations:

- The authors expect the publishers to print and distribute the book. They expect the book to be marketed and printed true to their manuscript with suggestions for improvements, correcting any errors and ensuring the layout is both sensible and attractive. They also expect to get paid a royalty on the sale of each book. The authors expect their book and message to receive the wider audience to which the publishers have access. The publishers expect the authors to write the book on time. They expect the authors to provide material that further develops their range of books and broadens their title list. They expect the book to be good enough to make them a profit on their outlay.

The Wider Context

Every contract is set in a wider context and the publishers hope that this title will be a valuable contribution to the debate on the issue of understanding and responding to difficult behaviour. As authors we are well aware of the substantial demand for training, support and resources relating to pupil behaviour. It is a theme high on the national agenda, reflected not only in the media but also in the wide range of government initiatives, guidance and legislation.

Central policies regarding social inclusion have generated a significant increase in interest and funding for programmes that span a wide spectrum of activity in key departments including education, health, community development and youth justice. More specifically, in the education field there has been a series of developments, many of which have been branded under individual programmes, including: Sure Start, Connexions, On Track, Crime Reduction in Secondary Schools, Healthy Schools.

Running in parallel has been the emergence of new guidance, some of which is underpinned by changes in legislation. Readers may be familiar with a number of related issues covered by official publications over the past few years including: target setting for pupils with social, emotional and behavioural needs (Qualifications and Curriculum Authority/Department for Education and Employment (QCA/DfEE) 2000), specialist standards for teachers (Teacher Training Agency (TTA) 1999), revised arrangements for special educational needs (DfEE 2000) and social inclusion (DfEE 1999).

One of the consequences of the major policy shift towards social inclusion has been a renewed pressure on schools to consider issues of pupil behaviour. The emphasis on increasing the inclusive capacity of schools is without doubt a challenging agenda, and some might argue that it is an impossible one. With targets to reduce truancy and exclusion, an expectation that specialist providers review their role within local contexts and an awareness of the impact of education failure in later adult life, schools are increasingly under pressure to explore how this might all be achieved.

Not surprisingly many schools have pointed out some of the inherent tensions in the central social inclusion policy. The shift towards inclusion is arguably undermined by the long-standing pupil achievement agenda where the emphasis has been on increasing academic standards, publication of ‘comparative’ school performance and a free-market approach to school admissions, most of which have been enforced through the inspectorate system.

All in all it has been difficult for schools to reconcile inclusive aspirations with the realities of a limited standards agenda. Conflicts within government guidance and competing legislative priorities have not helped to support schools. In particular, working towards a coherent approach to raising education standards for an increasingly wide range of pupils has often meant having to make a decision between meeting either one or other of the policy agendas.

We believe, sadly, that as a consequence of this apparent tension in policy, there is a limited range of outcomes. Teachers can feel faced with a situation in which either children must be to blame for difficult behaviour, or they as teachers are somehow to blame - a perspective that some smaller-minded national papers seem to favour. This position – that it must be either children or teachers that are to blame – is both negative and unsustainable. Our position is that it is very rare that either children or teachers fail; they simply do not. What fails both teachers and children are the perspectives that we use to get us out of difficulty. This observation lies at the heart of our hopes for this book and in the work that takes place in schools.

We are well aware that one of the objections raised by schools is that there are too many children that are ‘beyond’; that there is a growing number of youngsters for whom the ‘normal’, mainstream approaches to managing behaviour simply do not work. Invariably the perspectives used in understanding and responding to these cases are drawn from classic cognitive/behavioural theory - the standard, default mode for many schools.

As part of our contract with the readership for this book, we invite you to consider the possibility that the children beyond are actually telling us something about the limitations of conventional response to difficult behaviour. Techniques that may seem to ‘work’ for many children for much of the time may leave us bereft of ideas and success when it come to those most difficult cases. The outcome can be to condemn kids - and that can hold only fears for the future. The notion that instead we condemn adults in schools for not doing it right is equally futile – they are our best hope. In responding to the challenge of increasing the inclusive capacity of schools, we need to take a more critical look at the theory, technique and practice of what we do in schools.

In our work with schools we have noticed a common theme. In working on pupil behaviour the conventional approaches continue to make their mark. Colleagues welcome being reminded of the need to create structure through reinforcement and use consequence to discourage unwanted behaviours and recognise the impact of thinking on changing behaviour. Often colleagues present instances where the approaches fall short of success, and they need reminding that relying on a single perspective limits effective work with children.

Where we have started to introduce concepts drawn from Transactional Analysis (TA), something else happens. As an alternative model it illustrates, through familiar experience, new ways of understanding behaviour and of creating different insights into challenging situations.

What has TA Got to Offer Education?

We started with a day’s training for our team, using a few concepts from the TA approach. This led to further training and reading as the real implications of the ideas began to germinate. The concepts were easy to understand and use straight away and with practice they became more powerful. The more that was learnt, the more could be applied; yet a little was also enough to use. TA concepts can be taught in 30 minutes or developed over a number of days, are easily learned (by children as well as adults) and easy to apply. They are particularly good at helping to unravel the complex way humans communicate, so helping us to move forward and look at the way things could be better and less confused. This is why this book has been written – to make TA more accessible to mainstream educators.

It is because of our experience in introducing TA to schools that we have begun to recognise that it is an approach that can make a serious impact on how schools respond to the complexities of the central emphasis on social inclusion. Some of the ways in which TA helpfully contributes to school life are by:

- Promoting discussion and confidence in developing emotional literacy among staff and pupils.

- Providing a framework for managing conflict.

- Presenting an alternative model for understanding and using praise.

- Ensuring effective arrangements for working in partnerships with parents, pupils and other agencies.

- Building pupils’ confidence in responding to the challenges of learning.

- Promoting the mental health of both adults and children in schools.

What Makes TA such an Effective Approach?

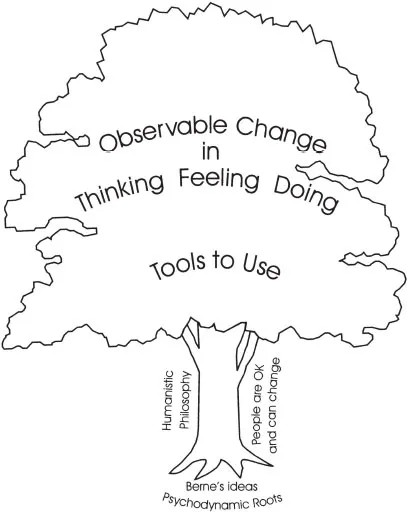

One way of describing TA is as a tree (Figure 1.2).

Like any tree it has roots which go deep into the ground; in this case the ground of psychodynamic theory, ascribing a person’s current attitudes and behaviour to early experience and interactions with others, whether positive or negative. Eric Berne, the originator of TA, was a psychiatrist and psychotherapist who had trained with Erik Erikson. Working with groups in the 1950s he studied intuition and observed behaviour to develop the concepts and visual models that became the core of TA theory. Berne himself practised and wrote about TA as a psychotherapy until his death in 1970, while others saw the potential application of his theories to organisations and education, and began to extend the areas in which TA can be used. Berne’s preferred description of TA was a ‘social psychology’ and/or a ‘social psychiatry’; a method by which observations of behaviour could be used to infer thinking and feeling, and insight into ‘what makes people tick’.

Figure 1.2 The TA tree

A tree also has a trunk, which gives it shape and structure, and through which nutrients pass from the ground to the leaves, flowers and fruit. The products of photosynthesis in the leaves return to nourish all parts of the tree and enable it to grow and become stronger and more robust. The trunk of the TA tree is a humanistic philosophy that maintains that every individual is intrinsically valuable, important and worthy of respect. Colloquially this has become known as ‘I’m OK, you’re OK’ or more accurately ‘I am OK with myself and you are OK with me; I respect and accept myself and you, and trust you to do the same to me’. The subtext of this belief is that when we behave towards those around us ‘as if’ we and they are ‘OK’ we invite ‘OK-ness’ in them. Teasing out the implications of this philosophy we can say that everyone (except the seriously brain damaged) can think for themselves, make decisions, problem solve, grow and change. People may, and often do, behave in ‘not-OK’ ways; this behaviour is the result of using ineffective strategies for communication and interaction which, with an OK—OK approach and the right information, can be changed.

The hope and optimism of this approach is manifested in its accessibility. Berne said ‘If something can’t be understood by an intelligent eight year old it isn’t worth saying’ (Steiner 2001). He opposed professional elitism and the use of complex language. When he was accused of over-simplifying concepts he responded those who want to make things difficult can sit at the over-complicated table over there; those who want to understand what’s going on can join me at the over-simplified table over here’ (Steiner 2001). The straightforwardness, immediacy and appeal of TA ideas have sometimes led to accusations of superficiality and TA being regarded as a ‘pop psychology’. This is unfortunate, and misleading, when such responses prevent people from appreciating the sound theory and creative, flexible application which are characteristic of TA writers and practitioners. The language of TA, and the terms used, are simple, and easy to understand; this is part of its accessibility and attractiveness.

The life and health of a tree can be seen in what it produces - its foliage, flowers and fruit. The roots and trunk are there to make these possible. Products of the TA tree include observable change in thinking, feeling and behaviour. These are the purpose of the tree’s existence, its reason for being. As well as bringing about change in people, TA as a system grows, changes and develops as new ideas emerge and are integrated into the basic theory. This is the nourishment that returns from the foliage to the roots and feeds the expanding trunk. TA is, above all, a theory of how personality develops, how human beings communicate, and how we can take charge of that to bring about desired changes – for individuals, relationships, groups, organisations and even whole societies.

Summary

TA is a cohe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Dealing with Conflict

- 3. Partnership Planning: Contracting in School

- 4. Raising Self-Esteem

- 5. Emotional Development

- 6. Developing a Positive School Culture

- Glossary of TA Terminology

- Further Reading

- Bibliography

- Index