- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sociology and Development

About this book

First Published in 1988. This stimulating and original book examines how sociological theory helps us to understand development. The author, writing with clarity and from long practical experience in the field of development, aims to show how different sociological theories cast light on the process of development both in the 'Third World' and in the 'Developed World'. He pays particular attention to the way in which that theory reflects the social, economic, political and racial assumptions of the time in which it originates. Tony Barnett maintains that the development process requires an understanding of the economic, cultural and political ways in which people organize their lives. This is facilitated throughout the book with the use of carefully selected and wide-ranging examples, quotations and case-studies which support and amplify ideas in the narrative - producing a truly interactive text that fully involves the reader. Sociology and Development is as illuminating about the developed world as it is about the underdeveloped world. But, as the author asserts, we are all citizens of the same world, increasingly - although unequally - sharing common resources, ideas and experiences. Sociology can tell us about the origins of this inequality and how it is maintained. Indeed, it is the book's main argument that an understanding of the relationship between sociology and the analysis of development can tell us much about whether, how and why development has occurred. Sociology and Development will be of great value to students of Development Studies, Third World Studies, Area Studies, and those wanting to supplement their work in economics and other development-rel,ated disciplines in both the social and environmental sciences. It is also a thought-provoking, entertaining and enlightening introduction for non-specialists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

1

Feeling the effects of development

The Labour Migrant

Imagine that you have been unable to find a job in your home town. Your family can 110 longer help you with money, the situation at home has become intolerable. You pack your more precious and necessary possessions and take off for another town, or even another country, aiming to make a new start. When you arrive at your destination, you are confronted by a large number of problems which need urgent solutions. You need food and shelter most urgently, but soon you will also need friends. You may speak with a different accent from the people in your new place, or you may even speak a different language. You have become a labour migrant.

Now imagine that you live in the African Sahel, that broad belt of desert and semi-desert which stretches across the northern half of the continent. There has been a drought which has gone on for years. The grazing has disappeared and as a result your family’s cattle are dead. For the past four years, the sparse crops which used to be grown have failed. There is no food locally, and the government has been unable to provide any relief. Indeed it has refused to admit that there is a problem, fearing that doing so might make the international banks, to which it is indebted, lose confidence, and reluctant to lend it any more money.

You decide to travel to the capital city, some 500 km away. After a difficult journey, mostly on foot, occasionally hitchhiking, you arrive and are faced with the problems of food, shelter, work, friends. Once again you are a labour migrant.

It is quite possible that in the first case, you couldn’t find a job because of the decline of some industry which had provided employment for your parents and grandparents. The industrial decline may have been the result of the loss of markets, because there were no longer colonies which had the habit of buying the products made in your town, or because other countries were able to produce those things more cheaply. In the second case, the effects of the drought may have been felt particularly keenly because your family’s traditional grazing land had been lost—perhaps an overseas company had leased part of it from the government, the part which was only used at times of very severe drought.

What is common to both of these situations is that you have been forced to make decisions, confront problems, not because you chose to, but because of events beyond your control.

Making Sense of the World

How can the sociology of development help us to make sense of this kind of situation? In many ways, sociology is always trying to make sense of the ‘outsideness’, the ‘otherness’ which we all feel when we find that we cannot do what we as individuals want because there are rules (legal—written down and administered by courts; moral—beliefs about what are ‘self evidently’ right ways to behave; religious—supported by beliefs in nonhuman agency) which prevent us.

Sociology was described by one of its early researchers, Emile Durkheim, as being the study of ‘social facts’ (see box 1.1).

BOX 1.1

SOCIAL FACTS

‘…that group of phenomena which may be differentiated from those studied by the other natural sciences. When I fulfil my obligations as brother, husband or citizen, when I execute my contracts, I perform duties which are defined, externally to myself and my acts, in laws and in custom. Even if they conform to my own sentiments and I feel their reality subjectively, such reality is still objective, for I did not create them; I merely inherited them through my education…. Here, then, is a category of facts with very distinctive characteristics: it consists of ways of acting, thinking and feeling, external to the individual, and endowed with a power of coercion, by reason of which they control him.’

(Durkheim, E., The Rules of Sociological Method, The Free Press, New York, 1964 pp. 1–3, first published in French in 1893, in English, 1933.)

What Durkheim was trying to pin down was the study of the otherness of society as it constrains or limits individual wishes and ambitions. He was asking how human societies ensure some degree of order, of regularity, of agreed rules of behaviour. In particular, he was concerned to discover how a moral community could be established during a time of great social, economic and cultural change.

This chapter was deliberately introduced with the image of the labour migrant. This is because throughout history, removed from their familiar surroundings and way of life, such people have always had to find ways of making a new life with new rules. Labour migrants have had to find new ways of solving the problems of order and morality as a result of the disruption resulting from changes affecting their lives. Such changes have included the slave trade (a vicious and enforced form of labour migration), the Scottish Highland clearances of the eighteenth century (see box 1.2), the movement of people from southern Europe to be ‘guestworkers’ in Germany, or more recently, skilled workers going from unemployment in the UK to high wages in the Gulf.

BOX 1.2

THE HIGHLAND CLEARANCES

From about 1775 onwards, the already impoverished small farmers of the Scottish Highlands were increasingly displaced as their land was taken over for profitable sheepgrazing. The English and Lowland Scot landlords raised rents, and a massive migration to North America began—for example to Nova Scotia (New Scotland) in Canada. Somebody writing in 1807 described one of these migrations:

‘The inhabitants of one district were required to pay an augmented rent for their…(land)…on which…they barely kept body and soul together…. They therefore took the unanimous resolution of seeking a new habitation in the wildest region of America…they hired vessels to transport 500 people to Canada; and the whole district took their departure—men with their pregnant wives, their children running at their feet and clinging to the breast—all, all took their departure, casting many a longing look at their well known and favourite mountains.’

(Richards, E., A History of the Highland Clearances, Croom Helm, 1983, p. 203.)

I have used the image of the labour migrant because, as well as making links from the past to the present, it also makes a link to a particular part of the past, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when there was considerable population movement within European countries. This was the result of radical changes in the organisation of both agricultural and industrial production. It was this period of radical change, as capitalism spread to become the dominant economic system, which gave rise to labour migration from one rural area to another, from country to town, and to the growth of cities (see box 1.3). It also led to the development of ‘sociology’ as an area of study—an attempt to understand the confusion, a science which could bring about order in this suddenly changing and confusing world.

BOX 1.3

THE CREATION OF LABOURERS IN ENGLAND

Writing in 1795, an observer of the English rural scene noted the following:

‘The practice of enlarging and engrossing (joining together) of farms, especially that of depriving the peasantry of all landed property, have contributed greatly to increase the number of dependent poor.

The landowner, to render his income adequate to the increased expense of living, unites several small farms into one, raises the rent to the utmost, and avoids the expense of repairs. The rich farmer also engrosses as many farms as he is able to stock; lives in more credit and comfort than he could otherwise do; and out of the profits of the several farms, makes an ample provision for one family. Thus the thousands of families, which formerly gained an independent livelihood on those separate farms, have been gradually reduced to the class of day-labourers. But daylabourers are sometimes in want of work, and are sometimes unable to work; and in either case their resort is to the parish…. And in the proportion as the number of farming families has decreased, the number of poor families has increased.’

(Rev. Davies, D., The Case of the Labourers in Husbandry, 1795, quoted in Cole, G.D.H. and Filson, A.W., The British Working Class Movements: Selected Documents 1789–1875, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1967, p. 3.)

This extract illustrates the effects of both the so-called industrial and agricultural revolutions. New technology meant that less labour was required for agricultural production and more for industry. Thus there was surplus of rural labour, and a process of stepped migration occurred. Labourers near the new factories moved to work in them; their places were taken by others from further away. In this way labour was redistributed across the whole country. But the process took time, and often there were pockets of surplus labour. These people had to be supported by the local parish.

A similar process of ‘labour transfer’ from rural to urban areas is taking place in many countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America today.

Sociology has its roots in the attempt to understand change.

Thus it is that the sociology of development encompasses all sociology. The question of what ‘development’ means will appear and reappear throughout this book, along with another one—why should we choose to use a word like ‘development’ (implying getting better—in other words a value laden word) when the other word ‘change’ might seem quite adequate? Box 1.4 explores some of the meanings of the word ‘development’. We shall look in more detail at some of the problems of defining development in chapter 9.

BOX 1.4

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY DEVELOPMENT?

In trying to answer this question I will talk in terms of three meanings and three problem areas.

The three meanings:

Development from within: this view says that any object—a plant, an animal, a society—has within it the tendency to change its form. When we talk about societies in this way, we assume that the possibilities and the direction of change are the result only of processes within that society.

Development as interaction: this view says that development of anything results from the interaction of an object and its environment. Thus, an animal or a society changes because of a combination of the qualities and potentials within the object and the opportunities and resources available in the environment.

Development as interpenetration: this view says that we cannot really draw a sharp distinction between an object and its environment. For example, an animal is made of materials from outside itself; its actions in feeding and housing itself alter that environment. When applied to society, this view raises the question of where are the boundaries of any society? How can we distinguish sociologically between, for example, Egyptian society —which is predominantly Muslim—and its ‘environment’ which also contains many other Muslim countries, the ideas, concerns and people of which may affect what goes on in Egypt.

Three problem areas:

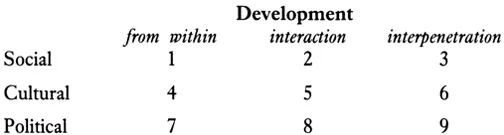

Each of the meanings of development can be applied to any number of problems, depending upon what we decide to focus. For example, we could be concerned with the development of the family and look at it in any of the three ways that I have described. It is usual in the sociology of development to be concerned with development at one or all of the following three levels—social, cultural and political.

This approach provides us with a neat table which shows that the three problem areas can each be analysed in three ways. You might like to look at this table and think about the implications of each of the nine possible approaches.

Max Weber tried to understand some of the causes and consequences of labour migration in Germany in the early and middle parts of the nineteenth century, when much ‘development’ was occurring in Europe (see box 1.5).

BOX 1.5

WEBER ON LABOUR MIGRATION

‘Weber emphasised that the capitalist transformation of labour relations in eastern Germany had tended to depress the workers’ standard of living…and he pointed to the frequent employment of women, the barracks-like living quarters of day labourers and their families, and the lack of wage supplements in the form of…gardening or a few head of cattle. This proletarianisation* of rural labourers was aggravated because employers resorted to the employment of Polish and Russian migrants—a preference due only in part to the foreigners’ willingness to work for lower wages, since their productivity also was lower than that of German workers. Polish and Russian workers were obedient because of their precarious status. They were also strictly seasonal labourers who could be forced back across the frontier, relieving their employers of the burden of any financial or administrative obligations.

The German workers were more demanding than the migrants in regard to nutrition and conditions of work, and because of these higher demands they lost out in the competition with Poles and Russians.’

(Bendix, R., Max Weber: an intellectual portrait, Methuen, 1962, pp. 19–20.)

Sociology as Biography and History

Sociology has been described as at least in part concerned with the intersection of biography and history. This is an important idea, because it directs our attention to two aspects of our study. One is the relatedness of different ‘disciplines’ which might appear to be quite separate. In fact, disciplines like sociology, anthropology, economics, economic history, history, geography, are only separate because people choose to make them so. As you read on, you will discover that this separation can be a hindrance to thought, it can make us think we have seen a problem in all its aspects when in fact we have excluded many relevant ideas and much information which might help us to understand the problem we are looking at. For example, if we were concerned with the question ‘what causes labour migration from a particular region?’ we would be giving a very partial answer if we only looked at the immediate causes, such as unemployment. A more satisfactory answer to the question would require that we examine the economic history of theparticular region in order to understand why there was unemployment, and whether or not it was likely to be long-term orshort-term.

The Sociology of Development

This discussion may seem to have come a long way from the sociology of development. But we are looking at just the kinds of questions with which al...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Part One: Introduction and Overview

- Part Two: Town and Countryside

- Part Three: Themes in the Sociology of Development

- Afterword

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sociology and Development by Tony Barnett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.