- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

J.N. Coldstream has now fully updated his comprehensive survey with a substantial new chapter on the abundant discoveries and developments made since the book's first publication.

The text is presented in three main sections: the passing of the dark ages, c.900–770 BC; the Greek renaissance, c.770–700 BC, covered region by region, and the final part on life in eighth century Greece. Its geographical coverage of the Mediterranean ranges from Syria to Sicily, and the detailed archaeological evidence is amplified by reference to literary sources.

Highly illustrated, including images of several finds never previously published, this follows the first successful edition as the essential handbook for anyone studying early Greek antiquity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Geometric Greece by J.N. Coldstream in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II

The Greek Renaissance c. 770–700 B.C. Regional Survey

4

Athens and Attica

Around 770 B.C. Athens enters a new phase of prosperity and artistic ferment, which also saw the final passing of the Dark Ages. After the obscurity and stagnation of the previous period, there are several signs that the emergence came quite suddenly. In the Levant, we have already noted (See Page) a burst of Athenian activity towards the end of MG II, and that is also the time when the circulation of Athenian pottery within the Aegean reaches its highest point before the sixth century.1 Commercial energy abroad was matched by expansion and affluence at home. Like most other regions, Attica affords evidence of a rapidly rising population. In the countryside, there are many sites on the coast and in the Mesogeia plain where the earliest post-Mycenaean finds are Late Geometric (See Page, fig. 43). In Athens itself, it appears from a count of wells within the Agora area2 that the population increased threefold in the course of the eighth century, and a similar impression is conveyed by a sharp rise in the aggregate of graves. The further expansion of the polis is indicated by the first use of three new cemeteries, all in outlying areas (fig. 44): one in the modern suburb of Kallithea, the second near the later Kynosarges Gymnasium, and the third well outside the later Dipylon Gate, by the present Odos Peiraios. The Kynosarges graves offer a wealth of gold jewellery, not seen in Athens since the mid-ninth century. From the Odos Peiraios cemetery the finds appear to have been no less rich; yet its chief distinction lies in a superb group of monumental vases which stood over the burials. Current fashion required that these monuments should forsake the large linear compositions of earlier times, and in their stead carry ambitious scenes of mourning, seafaring, and battle. To meet this new challenge, a first-rate artist was at hand; after the name often given to the cemetery since its discovery in 1871, he is known as the Dipylon Master. To him belongs the credit of inventing the rich Late Geometric style of Athens; and, in the long history of Attic figured vase-painting, his is the first hand which can be recognized by a consistent and personal manner of drawing.

As before, we shall begin with the pottery: first, the output of the Dipylon Master and his contemporaries (LG I), and then the work of the later eighth century (LG II) where the best figured drawing becomes increasingly fluent and dynamic, but the quality of Geometric ornament deteriorates to the point of collapse. From the scenes on the funerary vases, coupled with the evidence from the graves themselves, we can form some impression of the current burial practices in an age when inhumation was rapidly replacing cremation as the prevailing rite. Next we shall survey contemporary Attic work in more costly media—gold diadems and other jewellery, bronze, ivory—in which the new urge towards figured imagery also found expression. Finally, some general remarks will be hazarded about the nature of Attic society in the eighth century, and the changing fortunes of Athens in relation to the rest of Greece.

Pottery: the Dipylon Master and his Successors

Earlier essays in figured drawing (See Page) had been virtually limited to single men or women, single animals, single birds; inert, and usually tucked away in small, inconspicuous panels. Quite suddenly, around 770 B.C., more ambitious themes begin to appear. A monumental krater in New York,3 with supporting decoration still in the MG II manner, bears in its main panel a funerary prothesis where the dead man is laid out on the bier and surrounded by mourners, and in a lower zone an extended naval battle in which warriors fight in single combat on board ship. Similar duellists, in isolation, figure on the legs of a fragmentary tripod stand;4 and a miniature seafight is compressed, astonishingly, on to the two sides of a small skyphos from a late MG II grave at Eleusis.5

These pioneer works were shortly followed by the emergence of the Dipylon Master, inventor of the Late Geometric style. His main efforts were devoted to the fashioning and embellishment of monumental vessels for his aristocratic patrons, to stand over their graves. The demand, during his career, seems to have been phenomenally high; at least thirty-five LG I grave monuments are known— if only from small fragments—and twenty-one are from the Dipylon Master’s hand or workshop. These gigantic vases, well over 1m. high, are the last representatives of two time-honoured Attic forms: belly-handled amphorae for women, tall-pedestalled kraters for men. All bear scenes of mourning around the bier; the kraters, in addition, show chariot processions, a retinue of fullyarmed warriors, and—during the workshop’s prime (LG 1a, c. 760–750) scenes of fighting on land and sea. This sudden eruption of figured painting is all the more astounding, coming as it does after four centuries when any form of representational art had been extremely rare. To judge from surviving fragments, a complete battle-krater from the Dipylon Workshop would have borne well over a hundred figures; work on this grand scale was never again attempted by vasepainters until the black-figure scenes of the early sixth century, the time of the François Vase.

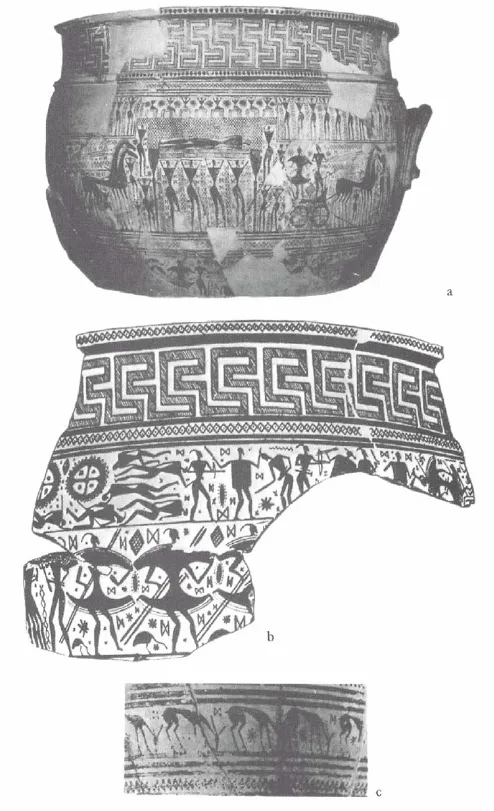

Paris A 517 (fig. 33a), one of the largest extant fragments, illustrates the Master’s own style. In the main scene on the front (the back is missing) he shows us the prothesis of a nobleman, amidst a retinue of chariots and foot-soldiers; the procession continues in the lower zone. Under the surviving handle, a warship with its rowers may perhaps allude to the interests of the dead man. All round the bier, groups of mourners tear their hair; although drawn in elevation, their grouping in relation to the bier is seen from bird’s-eye view.6 Each individual figure, too, combines two different viewpoints, so that every limb shall be visible; chest and arms in frontal view, head and lower body in profile. In the chariot teams a similar desire for clarity, leaving nothing to the viewer’s imagination, is displayed in the careful definition of eight legs and two wheels side by side; on the bier, the checked shroud is drawn back to reveal the corpse. While it is not always easy to see, in this impersonal style, whether the mourners are men or women,7 this painter has at least taken trouble to distinguish the sex of his dead patron; this we can see by comparing the prothesis on the wellknown amphora Athens 804, where the deceased lady is given a long robe.

This tense, static scene has a dynamic counterpart in Paris A 519 (fig. 33b), from a krater painted by one of the Dipylon Master’s closest associates; probably from the back of a krater whose front was reserved for the prothesis. In the upper zone a grim land-battle is being waged: casualties on the left, then three groups in combat, culminating in the collapse of a huge warrior from his chariot, wearing the so-called Dipylon shield. His peers, below, hurry to the rescue,8 one foot in the air; in between, baleful birds of prey look forward to the outcome; behind, another combat involves a pair of Siamese twins. The clarity, once again, is remarkable. The silhouette technique requires that there shall be no substantial overlapping of figures; so the dead bodies appear to be floating in mid-air, and at the left of the lower zone we can be reasonably sure that Siamese twins are intended,9 not two warriors side by side. The figures themselves are distinguished from one another by simple, generic traits. Death is conveyed through bent wrists and spread fingers (top left), or by a large, staring eye (top right).10 The surviving warriors can be sorted into their respective armies according to their equipment: square shields versus Dipylon shields or no shield. Above all, human arms are always clearly drawn, so that we immediately recognize the activity and function of each person. And yet the underlying anatomy of every figure painted in this workshop—be he warrior, archer, rower, charioteer, or mourner—conforms to the austere archetype established by the Master himself, quite distinct from any previous experiment: abnormally tall in stature, curves reduced to a minimum, and the frontal chest presented as a slim isosceles triangle, whose sides are produced by the upper arms of the mourners. Equally individual are the horses (fig. 33a), with their tall necks, the elegant double curve of their shoulders, and the backward thrust of their hind legs.

The figured repertoire of this workshop is completed by the narrow friezes of grazing deer (fig. 33c) and kneeling regardant goats, always purely decorative in function, each animal being repeated in a standard pose. Here we have one of the few ideas in Geometric figured painting which was surely borrowed from the Near East, perhaps directly from Levantine ivory reliefs,11 or perhaps at second hand through contemporary Attic diadems (See Page). By his adoption of the animal frieze, the Dipylon Master was setting a precedent, fully to be exploited by the vase-painters of the next two centuries.

FIG. 33 ATHENIAN LG Ia POTTERY, DIPYLON WORKSHOP (a) Paris A 517, H. 58; (b) Paris A 519, H. 38.5; (c) Athens 811, detail

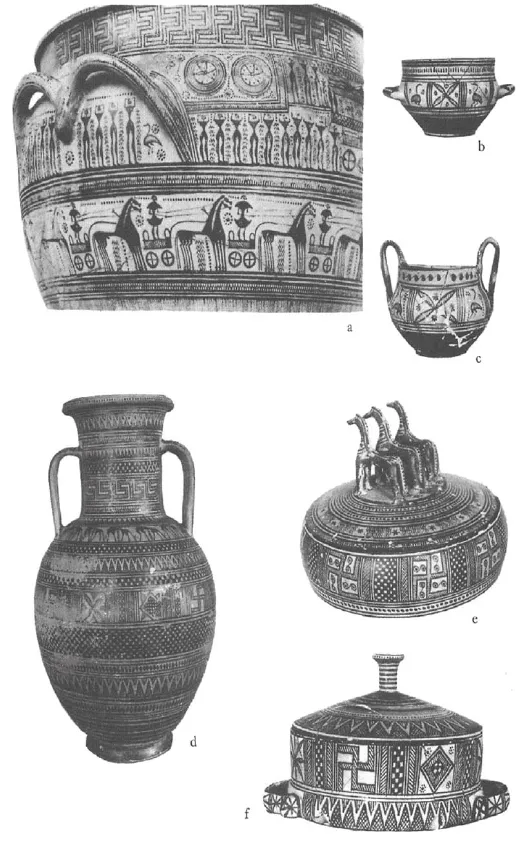

FIG. 34 ATHENIAN LG I POTTERY (a) Athens 990, detail (total H. 123); (b) K gr. 24, H. 9.2; (c) K gr. 24, H. ii.6; (d) K gr. 72, H. 52; (e) Agora gr. 18, H.8; (f) K gr.71, H. 7.5

In his handling of linear ornament, he was no less of an innovator than in his drawing of figures. Geometric decoration had been steadily growing in intricacy since 800 B.C., yet even at the end of MG II much of the surface was still habitually covered with dark glaze. The Dipylon Master now breaks new ground in decorating virtually the whole vase with a continuous web of ornament, but without thereby obscuring the underlying shape. Thus the three focal areas of a larged closed vessel—belly, shoulder, and centre of neck—are emphasized just as effectively as before, either by figured scenes, or by linear designs more massive than anything seen before: huge complex meanders, or lozenge patterns resembling elaborate tapestries (GGP pl. 7d,e). A third possibility was to divide a main field vertically into square panels recalling the metopes of a Doric temple, often with narrow ‘triglyphs’ intervening (e.g. fig. 34f). This idea, occasionally used in the Dipylon Workshop, became extremely popular elsewhere; and, like the habit of overall decoration, it forms an important ingredient of the Attic LG style.

Before leaving the subject of linear ornament, we should note that the Dipylon Master was also a pioneer in thinking out small motifs suitable for filling vacant spaces in the figured fields. These filling ornaments have the effect of binding the figures into a ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Charts

- Maps and Plans

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- I: The Passing of the Dark Ages c. 900–770 B.C.

- II: The Greek Renaissance c. 770–700 B.C. Regional Survey

- III: Life in Eighth-century Greece

- Epilogue

- Glossary

- Bibliography and Site Index