![]()

1 Introduction

What’s economics got to do with it?

• Environment is all the living and non-living things around us

• Economy is the supply and use system of goods and services

• Environment and economy interact with good and bad effects for our well-being

• Environmental economists rely on adjusting markets and technology to maintain environmental services and economic growth

• Ecological economists call for curbs on or changes to economic growth, which they see as the culprit of environmental decline

• Sustainability economics encompasses micro- and macro-concerns of sustaining economic growth and development

‘It’ refers to the environment as a key concern of sustaining economic activity and human health and well-being. This first chapter explores the interaction of the environment and the economy as the cause of environmental problems – problems that threaten the lasting supply of both environmental services and economic products. Financial flows of credits and debts may also sustain or undermine economic activity. Purely economic and financial issues are, however, the subject of standard economic analysis and are not further explored here.

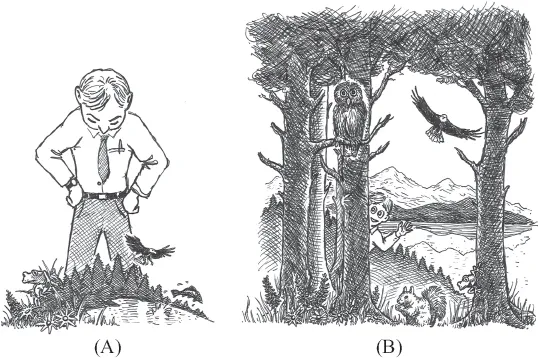

Let us first find out what is behind the basic notions of ‘environment’ and ‘economy’. The nineteenth-century German biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel (1866: 286) defined ecology as the ‘total science of the relationships of the organism with its surrounding outer world’. Replacing ‘organism’ by ‘human beings’ gives us a definition of the human environment: it includes all of nature, other humans, and human-made goods such as streets, buildings and computers. Different views about the place of humans in their natural environment characterize two basic attitudes towards nature. ‘Deep’ environmentalists see people as a part of nature, on a par with other living beings. In contrast to this eco-centric view, the more popular anthropocentric view looks for nature’s benefits for humans: it sees nature as a provider of services in support of human life and well-being. Figure 1.1 illustrates the two worldviews that gave rise to different schools of thought about human interaction with the natural environment.

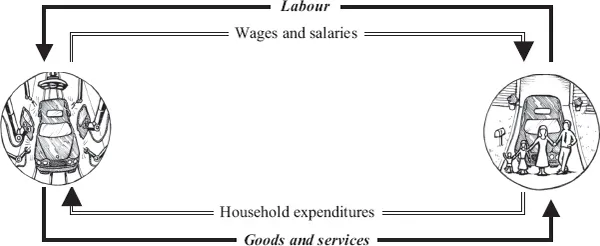

Figure 1.2 is a simplified description of the exchange of goods and services in markets. It gives a first impression of what the economy is. Households provide work for enterprises, which remunerate labour with wages and salaries. As consumers, households use their income to buy the goods and services produced by enterprises, or they save part of their income for future purchases. More detailed descriptions of economic activity include governmental and non-governmental organizations and financial institutions. The national accounts define these economic agents more rigorously and measure their transactions in units of money. Economic theory attempts to explain and predict the behaviour of economic agents and their effects on the economy.

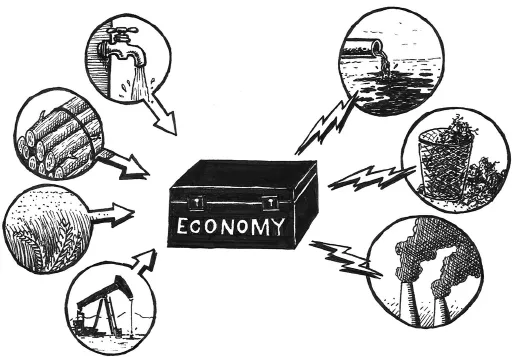

So what is the problem? The problem is that environment and economy interact, and not always in good ways. Nature sustains life on earth with oxygen, food, water, energy and habitat. It also supplies the economy with natural resources of timber, oil, metals, minerals, livestock and agricultural products. Moreover, nature takes care not only of its own wastes, but also of wastes and pollutants from the economy. On the other hand, natural disasters and overuse of nature’s services by humans take a toll on human health and well-being. Figure 1.3 shows nature’s services as flows of natural resources from the environment to the economy and back into the environment as wastes and emissions. The uses and abuses of environmental services create good and bad effects for human well-being. Economists call the good effects utility and the bad ones disutility or damage, when they refer to individuals. For society or nations, they label the sum of these effects as an increase or decrease of economic welfare.

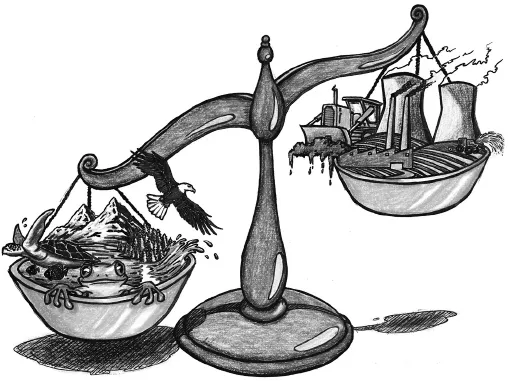

Figure 1.1 Anthropocentric (A) and eco-centric (B) view of the human environment. View A sees nature as the provider of natural resources and services of recreation and waste disposal. View B rejects the dominance of humans over nature and considers all living things as equal in their rights to life and reproduction.

Figure 1.2 Economic exchange system. Enterprises produce goods and services. Households work for enterprises and spend their income on purchases of goods and services.

Figure 1.3 Environment–economy interaction. Source functions of supplying natural resources and recreation, and sink functions of absorbing pollutants and wastes are the main environmental services for the economy. Environmentalists often treat the economy as a black box, whose inner workings are largely irrelevant when facing environmental disaster (see Chapter 2).

Nature’s capacity for providing environmental services is limited. Environmentalists hold that excessive economic and demographic growth and associated technology destroyed much, if not most, of our natural resources. They see the growth of the human population and its consumption and production patterns as the main cause of environmental deterioration. The rather tautological IPAT equation (Ehrlich and Holdren 1971) summarizes this view:

Here I is environmental impact, P is population size, A = GDP/P is affluence and T = I/GDP is technological impact.

As discussed in Chapter 3, exponential population growth could bring about a Malthusian decline in welfare. Population growth and concentration in urban areas also overburdens the planet with people’s wastes. A ‘full world’, full of buildings, infrastructure and people and their wastes, is overloading the planet’s carrying capacity for humans and their artefacts (Daly 1996). Such a world is likely to collapse* unless we find ways of drastically reducing the use of the natural environment. Mainstream economists doubt that the end is near. They put their faith in human ingenuity and in the power of markets to deal with increasingly scarce environmental services.

Whatever the outlook for our future, there is no question that there are ultimate limits to the earth’s funds of natural resources and absorptive sinks for our wastes. The recognition that these limits might undermine economic growth and development is the basic premise for a new field of study – sustainability economics. Environmentalists and economists disagree, however, on when, if ever, we will hit these limits, what will be the effects, and what we should do about it. This is what this book is about: to find out if and how the natural environment can sustain economic activity and welfare – now and in the future. Finding an efficient balance between maintaining environmental services and generating income, wealth and welfare is the main objective of sustainability economics (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Finding the balance. Sustainability economics explores synergisms and trade-offs between economic production and consumption and environmental quality.

The emphasis is on efficiency, as it is mostly ignored in advocating sustainable development.

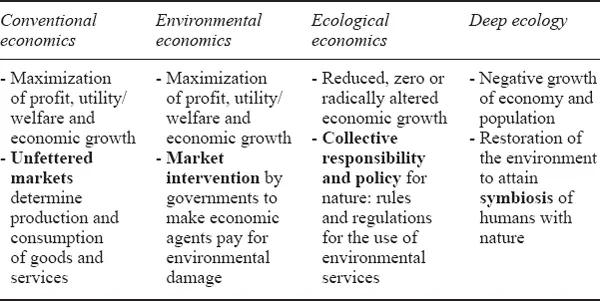

Distinct and often contradictory views about how to assess and tackle environmental problems, and consequently sustainability, are at the origin of different schools of environmental-economic thought. Table 1.1 summarizes (and simplifies) these schools under different categories of ‘eco-nomics’ (Bartelmus 2008). The four categories show increasing intensity of intervention in the economy for the sake of environmental protection. Conventional (neo-classical) economics seeks income and welfare maximization without considering environmental constraints. Environmental economics accounts for the scarcity of environmental services as an additional cost of otherwise unrestricted economic activities. Ecological economists believe that the dire situation of a full world calls for curbs on or at least radical changes to economic activity; they favour rules and regulations over market instruments to slow down or halt economic growth. Deep ecologists are least concerned about economic scarcity and efficiency; adhering to the egalitarian eco-centric view, they seek a symbiotic relationship with nature. In their view, only a return to lower production, consumption and population levels can save the earth.*

Table 1.1 Schools of eco-nomic thought

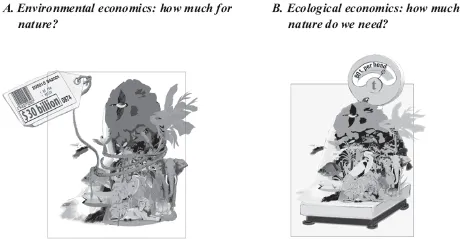

Even the less radical environmental and ecological economists adopt different approaches. Figure 1.5 illustrates a distinct polarization in dealing with environmental problems and the sustainability of the economy:

• environmental economists cost and budget environmental deterioration (part A) for making economic activity environmentally accountable and sustainable; and

• ecological economists warn us about the non-sustainability of current economic activity, stemming from its physical ‘burden’ or pressure on the environment (part B).

This book addresses the sustainability of economic performance and development mostly at the national level, with some excursions into local and global issues. However, micro-economic behaviour of households and enterprises is very much part of the picture: this is the case when it comes to explaining and influencing individual preferences for economic and environmental goods and services. To address the interaction of micro- and macro-planning and policy at local, national and international levels a combined approach is chosen, rather than the standard split into micro- and macro-economics. Note also that the crude distinction between ecological and environmental economics serves didactic purposes. Related schools of eco-nomics modify and sometimes combine the concepts and methods of the two basic approaches.* The timeline in the Appendix gives a historic overview of the key players responsible for combining environmental and economic analysis. It shows, in particular, the merging of thermodynamic physics and ecology in what became ecological economics, and the extension of mainstream economics into the use of environmental services, the foundation of environmental economics.

Figure 1.5 Environmental-economic polarization. Part A illustrates the monetary analysis of environmental economists; US$ 30 billion is a green accounting estimate of environmental cost in West Germany (see Chapter 6). Part B indicates the physical assessment of environmental impacts by material flow accounts; for industrialized countries the total material burden of natural resource ...