![]()

1

What is crime science?

Richard Wortley, Aiden Sidebottom, Nick Tilley and Gloria Laycock

Introduction

Crime science is precisely what it says it is – it is the application of science to the phenomenon of crime. Put like this, it might seem that crime science simply describes what criminologists always do, but this is not the case.

First, many of the concerns of criminology are not about crime at all – they are about the characteristics of offenders and how they are formed, the structure of society and the operation of social institutions, the formulation and application of law, the roles and functions of the criminal justice system and the behaviour of actors within it, and so on. For crime scientists, crime is the central focus. They examine who commits crime and why, what crimes they commit and how they go about it, and where and when such crimes are carried out. The ultimate goal of studying crime is to learn how to reduce it.

Second, by no means is all criminological research scientific, nor does much of it aspire to be so. The scientific method is broadly defined as the systematic acquisition and testing of evidence, typically involving measurement, hypotheses and experimentation. There are branches of criminology (such as cultural criminology, see Hayward & Young, 2004) that eschew this empirical approach and instead rely on interpretive methods of enquiry that emphasise the subjective nature of knowledge. Moreover, when we examine the operation of the criminal justice system we encounter a great deal of policy and practice that is based on popular sentiment, ideology, political expediency, intuition, moralistic assumptions, ‘good ideas’ and ‘what we have always done’ rather than good science. Crime science is an evidence-based, problem-solving approach that embraces empirical research. Furthermore, the ‘science’ in crime science refers to more than the traditional fare of sociology, psychology and law that currently dominate criminology. The scientific theories, methods and findings needed to reduce crime may come from any discipline across the social, natural, formal and applied sciences.

Thus, crime science is at the same time more focused yet broader than criminology. It has the narrow mission of cutting crime but it is eclectic with respect to how this might be done and who might contribute to this mission. Putting the above elements together we arrive at the following definition:

The term ‘crime science’ was created as a banner under which those interested in empirically based approaches to crime reduction might gather, be they within or beyond criminology. The theories and methods used in crime science are largely borrowed from existing approaches; what makes crime science distinctive is the deployment of these theories and methods around the unifying goal of crime reduction. While a growing band of researchers self-identify as crime scientists, there is much crime science also undertaken by researchers who are unfamiliar with the term. We trust that these researchers will not mind being badged fellow travellers.

This handbook is intended as a crime-science manifesto. In it we set out the case for crime science, define its key features, and showcase examples of crime science in action. This introductory chapter is divided into two main sections. In the first we trace the roots of crime science back to environmental criminology, describing some of the key philosophies and theoretical approaches that have helped shape the development of crime science and that remain important underpinnings. In the second section we discuss three defining characteristics of crime science, namely its determinedly outcome-focussed approach on crime reduction, its scientific orientation, and its embracing of diverse scientific disciplines.

Environmental criminology roots

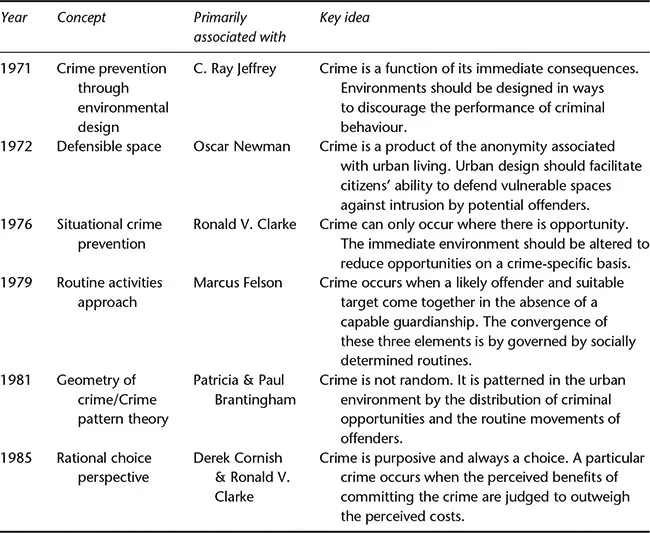

During the 1970s, in both the USA and the UK, questions were raised about the extent to which the treatment of offenders could reduce crime. Offender treatment programmes were the dominant model for crime reduction at the time, and so concerns that ‘nothing works’ (Martinson, 1974) became something of a demotivating mantra for those working in the criminal justice system, particularly in prisons. It also left a policy vacuum on what to do about crime. From the early 1970s to mid- 1980s, a series of seminal publications appeared in the new field of environmental criminology that informed an alternative crime-reduction model (Table 1.1). From disparate disciplinary roots and with different foci, these approaches shared a common interest in crime events (rather than criminality) and the immediate circumstances in which crime occurs (rather than presumed distal causes) (Wortley & Townsley, 2017). In this section, we trace the development of environmental criminology, show how the various strands developed and came together to form a coherent perspective, and highlight the key assumptions and methods that influenced the conceptualisation of crime science.

Crime prevention through environmental design

Three years before Martinson’s (1974) ‘nothing works’ report, C. Ray Jeffery (1971) published a book that anticipated the attack on rehabilitation and set out a radical prescription for crime prevention. Entitled Crime Prevention through Environmental Design – universally referred to as CPTED (and pronounced sep-ted) – the book presented a wide-ranging critique of the then dominant (and largely still current) criminal justice policies and practices. Jeffery argued that we lack the scientific knowledge to rehabilitate offenders and that we should instead focus on supressing their criminal behaviours. This required a shift in attention away from the presumed criminal dispositions of offenders and onto the immediate circumstances that facilitate or inhibit criminal acts. Jeffery was strongly influenced by arch behaviourist B. F. Skinner’s (1953) model of operant conditioning. In essence, operant conditioning holds that our behaviour is contingent upon the consequences it produces – behaviour that is rewarded is reinforced and behaviour that is punished is discouraged. Applying this principle to crime, Jeffery asserted that ‘there are no criminals, only environmental circumstances that result in criminal behaviour. Given the proper environmental structure, anyone will be a criminal or a non-criminal’ (Jeffery, 1971, p. 177).

Table 1.1 Chronology of seminal approaches in environmental criminology

Jeffery proposed a new discipline of ‘environmental criminology’ to inform criminal justice policy and to promote crime prevention. In this new discipline, he wrote:

1 Scientific methodology is emphasized, in contrast with an ethical or clinical approach, limiting observations and conclusions to objective, observable behavior which can be verified

2 The approach is interdisciplinary, cutting across old academic boundaries and borrowing freely from each. The human being is regarded as a total system – biological, psychological and social

3 The human being is regarded as an input-output system, capable of receiving messages from and responding to the environment. Communications, cybernetics and feedback are critical concepts

4 Adaptation of the organism to the environment is the key process. Behavior is viewed as the means by which the organism adapts to an environmental system

5 A systems approach is used wherein emphasis is placed on the interrelatedness of parts, structural-functional analysis, and the consequences of action in one component of the system for the system in general

6 Future consequences of action, rather than past experiences or variables, is emphasized in behaviorism and in decision theory

(Jeffery, 1971, p. 167).

Crime Prevention through Environmental Design is a remarkable book. Written nearly 50 years ago, it was in many ways ahead of its time and it retains a currency few academic books of that age can claim. Elaborating on the nature of criminal behaviour, Jeffery took the deeply unfashionable view that it should be ‘regarded as a biophysical phenomenon explainable in the same terms as other natural events’ (p. 185). Even with the genomic revolution of recent years, many criminologists today remain resistant to according a meaningful role in crime to biological processes. More generally, Jeffery argued that ‘science and technology can be applied to the prevention and control of crime’ (p. 212). In response to the traditional dominance in criminology of ‘law, sociology, and psychology’ he called for radical ‘interdisciplinarity’ that embraced ‘newer disciplines such as urban planning, public administration, statistics, systems analysis, computer engineering, and biopsychology’ (p. 262). Few criminology departments today encompass the breadth of disciplines Jeffery advocated. As we will show later in this chapter, bridging the social and physical sciences as Jeffery proposed is even more important now as we seek to respond to the increasingly technologically-aided nature of crime of the 21st century. With just a little tweaking, Jeffery’s six principles of environmental criminology could be turned into a modern-day blueprint for crime science.

Most crime researchers will know of CPTED but we suspect that few have actually read Jeffery’s book. The biosocial model of behaviour and the environmental determinism that underpinned his approach to prevention proved unappealing to mainstream criminologists. Moreover, even for those researchers interested in environmental criminology, his book was quickly overshadowed by another book published the following year, Oscar Newman’s (1972) Defensible Space: Crime Prevention through Urban Design.1 Jeffery’s term CPTED has endured but his approach has been supplanted: what most people think of as CPTED is in fact Newman’s concept of defensible space.

Defensible space

Despite the similarity of the titles, Jeffery’s and Newman’s books are very different. As his title suggests, Newman was narrowly concerned with how the design of buildings, streets and open spaces influenced crime in urban settings. His central premise was that urban crime is a result of the anonymity and social fragmentation that characterises modern cities. People do not know their neighbours and they feel little personal investment in the surrounding environment. This in turn leads to a lack of vigilance and protective action by residents with respect to crime and antisocial behaviour. To Newman, what was needed to prevent crime was the stimulation of a sense of territoriality in residents. If residents could be encouraged to feel a greater sense of investment in their surroundings then they would be more likely to take actions that would defend those areas against intruders. So-called ‘defensible space’ could be created through a ‘range of mechanisms – real and symbolic barriers, strongly defined areas of influence, and improved opportunities for surveillance – that combine to bring an environment under the control of its residents’ (Newman, 1972, p. 3).

Narrowing the prevention task to the creation of defensible space has taken the Newman version of CPTED down a separate pathway to that taken by environmental criminology more generally. CPTED exists today as a more or less standalone model concerned principally with the design of the built environment (Armitage, 2017). Nevertheless, Newman’s Defensible Space makes three important contributions to environmental criminology and ultimately to crime science.

First, Newman showed by example the value of expanding the disciplinary reach of criminology beyond the usual suspects. As an architect, Newman was one of the first non-social scientists to write about crime and its prevention. Environmental criminology is based on the premise that crime is the combined effect of the characteristics of the person and the situation in which the crime is performed. Because criminology largely comprises social scientists, there is an abundance of research addressing the nature of the person. Newman on the other hand could speak with authority on the situational side of the equation, providing informed advice on what architecture could offer to environmental criminology.

Second, Newman demonstrated the importance of operationalising prevention advice. Jeffery’s CPTED was a polemic, long on theory but short on application; Defensible Space in contrast was essentially a how-to manual. Newman gave explicit instructions and offered many concrete examples of how to prevent crime: low-rise buildings have less crime than high-rise buildings; even low fences will deter many potential intruders; windows should look outwards onto the street so that passers-by can be observed; graffiti and rubbish invite disorder, and so on. Many of the principles of defensible space could be readily converted into policy statements and even codified into building and town-planning regulations.

Finally, Newman taught the value of understanding and altering the behaviour of those who were the potential victims and observers of crime. Where Jeffery presented a detailed psychological model of the offender, Newman barely mentioned offenders. His focus instead was on how urban design can change the behaviour of residents so that they might exercise greater levels of guardianship and thereby deter potential offenders. The focus on the role of residents as potential victims and guardians introduced additional elements to the crime dynamic, underscoring the point that crime prevention was not exclusively about dealing with offenders, nor was it the sole province of the criminal justice system.

Situational crime prevention

The next major contribution to environmental criminology came with Ron Clarke’s situational crime prevention (SCP). In fact, Clarke’s early writings on the role of situations in crime pre-date Jeffrey and Newman. Researching absconding from residential schools for juvenile offenders, Clarke found that the best predictors of absconding were institutional factors rather than any personal characteristics of the absconders. The best way to prevent absconding was not to try to identify potential absconders, but rather to change the way that institutions were built and run (Clarke, 1967). But it was in Crime as Opportunity published by Clarke and colleagues a decade later (Mayhew, Clarke, Sturman, & Hough, 1975) that the conceptual foundations of SCP were first set out in a comprehensive way, although the term itself was not used until Clarke’s 1980 paper, ‘“Situational” Crime Prevention: ...