Chapter 1

Learning how to learn

You read a book from beginning to end. You run a business the opposite way. You start with the end, and then do everything you must to reach it.

Harold Geneen

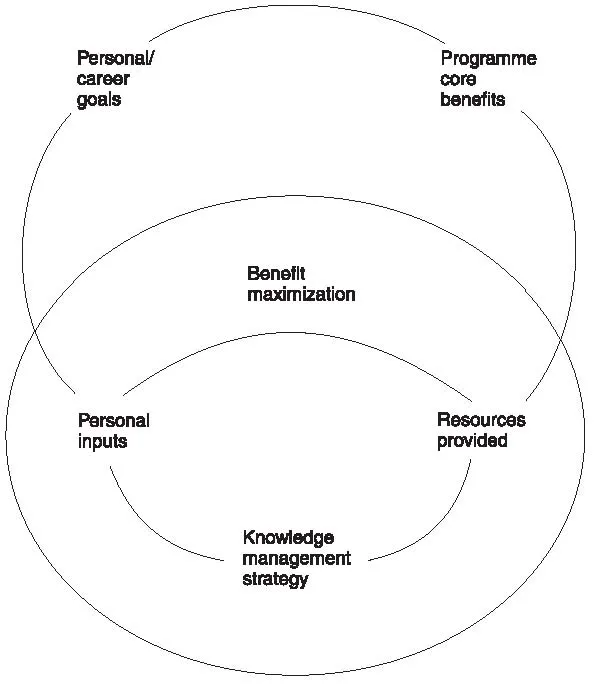

Before getting into the MBA programme proper, it is first necessaty to devote some time to the fundamental ideas on which this book is based. In particular, there are two important processes that go on all during the MBA programme. The first, which we have already referred to, is benefit maximization. The second, more practical process, is knowledge management. To consider how these work and are related, consider the following six points:

- Education is a service. Every student has some input into the education they receive. What you take out depends in part on what you put in.

- Every MBA student will have a set of personal and career goals, what they hope to achieve from the programme. These will help to shape the learning experience.

- Every MBA programme offers a series of core benefits, which are built into the design of the programme.

- Depending on the student’s goals (2), he or she can work to maximize the benefits (3) he or she receives from the programme, and this in turn will help to define more clearly his or her own input (1) into the programme.

- Once this picture is clear, the student can then work out what resources are needed, developing a ‘resource-based’ view of the MBA programme.

- Finally, from this basis, the student can define a knowledge management strategy which will enable maximization to occur.

Figure 1.1 below shows how these elements interrelate. The student begins by assessing the benefits of the programme in light of his or her personal and career goals, and then works out how to maximize those benefits. (The maximization process can help to further define those goals, hence this is shown as a circular process.) Maximization is in turn a circular process; the resources provided by the programme combine with personal inputs to develop a knowledge maximization strategy; and, as this develops, so the types and levels of resources needed can change (hence this too is shown as a circular process)

Figure 1.1 Relating goals and motivations to resources and strategy

This is probably about as clear as mud. Don’t worry too much; the chapters which follow should make it clear how this works. The main theme, put more simply, is to focus on goals and then work out how to get the most out of the MBA programme to propel you towards those goals.

When should all this happen?

Ideally, of course, you will have had a chance to work all this out in advance, before the programme starts. You will be clear about your goals, and you will have a good idea of the benefits of the programme. You will know what resources are available, and you will have some idea of what you will need to put into the programme. Thus you can begin to design the two loops, benefit maximization and knowledge management.

But conditions are seldom ideal, and there is every chance that you will need to do a lot of this in the early stages of the programme. Chapter 2, getting started, deals with the vital first few days of any MBA programme.

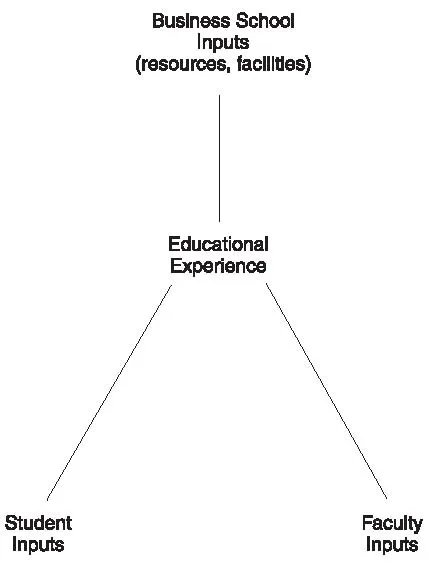

Education and the service process

In education, as in all services, the quality of the service depends to some extent on the consumer. To use the jargon of the services marketing experts, ‘the consumer is part of the production process’. When we go to restaurants, for example, we make choices from the menu, interact with the staff and sometimes other customers, consume the food and wine we have ordered and so on. We do not passively accept what the staff provide us (well, not in most restaurants, at least), we are part of the process.

So it is with education. Learning is not a passive process; one cannot simply sit in a classroom and let knowledge transfer from lecturer to student through some form of osmosis. We learn through interacting with others, lecturers and staff, fellow students and so on. Our willingness to learn, our learning skills (listening, analysing, communicating, etc.) and our personal goals and needs all have an impact on what we learn and how we learn it.

Real learning is an active process. It involves questioning information which is found in lectures, textbooks and cases and so on, and analysing it for value. It involves seeking out resources and people who may have information or knowledge which can be of use. It involves learning from real-life, everyday situations, not just in formal settings.

Learning is not about absorbing information. It is about gathering and using knowledge. The importance of the student’s own role in this process cannot be overemphasized. No matter how good the teaching materials, no matter how high the quality of the lecturers, one has responsibility for one’s own learning.

Figure 1.2 The service production process in education

Further information

If the reader is coming from a background in services marketing, then much of the above will already sound familiar. If not, and if the explanations given here are insufficient, then there are several good books on services marketing which go into these concepts in more detail. Recommended for novice readers are John E.G. Bateson and K. Douglas Hoffman, Managing Services Marketing (Fort Worth, TX: Dryden, 1999) and L.L. Berry and A. Parasuraman, Marketing Services: Competing Through Quality (New York: The Free Press, 1991).

Setting and defining goals

Everyone enters an MBA programme with his or her own highly personal set of goals. Generally, though, each of these goals falls into one of two categories:

- professional, which usually means advancing one’s career, changing careers, getting a better job, or starting one’s own business

- personal, usually relating to self-development, vision and so on, and possibly also including developing personal and interpersonal skills such as communication and networking

There isn’t really much more to be said on this subject (this is a rather obvious point anyway), except to acknowledge that most people’s goals are complex rather than simple, and likely include elements of both categories above. And in fact, a mix of the two is by far the healthiest option. A concentration on the professional over the personal can lead to a narrow-mindedness and lack of vision that can compromise rather than assist professional advancement. Similarly, too much focus on the personal and not enough on the professional can result in a well-rounded person with a great vision – and no job.

Me? A student?

In the 1990s there arose a prejudice against referring to people taking MBA programmes as ‘students’. It was felt that ‘student’ referred to undergraduates, and was not appropriate to mature, experienced people. Calling MBA programme members students was seen as an affront to their dignity.

But ‘participants’, the fashionable alternative, implies a distance between the people and the programme. Other options are not much better. And anyway, is it such a bad thing to be a student?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a student as ‘a person studying in order to qualify himself or herself for some occupation, or devoting himself or herself to some branch of learning or investigation.’ To me, this seems a highly appropriate term for people on MBA programmes, and I shall therefore refer to them as ‘students’ throughout this book.

Core benefits

The benefits offered by MBA programmes are complex and variable, but most programmes offer at least some of the following, and many offer most or all:

- skills development, including acquiring new skills and improving existing ones. This benefit is especially valuable for students coming in from a fairly narrow functional background (marketing, finance, HRM, etc.) and seeking either a change in career path or a broad package of skills suitable for general management.

- global vision, or more specifically, learning to work, live and manage in the global marketplace. Globalization is a bit like electricity; everyone sees its effects, but rather fewer people know how it works. Global experience and outlook is seen as an important benefit of many programmes.

- a broader outlook, or in general terms, learning to look outside one’s own firm, business sector, business function and so on and to develop a greater appreciation of how firms, functions, markets and so on interact. Schopenhauer once wrote that ‘every man takes the limits of his own field of vision as the limits of the world’. Breaking out of this way of thinking leads to the next benefit,

- integrated thinking, or learning how to visualize both the whole and the interaction of the parts, whether in terms of firms, markets, business systems or whatever. This is seen as one of the most important components of management today, and also of such concepts as creativity and innovation. This also includes seeing oneself as a part of a system, networking, team management and so on.

- preparation for leadership, acquiring both the skills and the mindset necessary to be a successful leader of an organization. Confidence, decision-making ability and communications skills, for example, are seen as essential ingredients.

- knowledge management, the latest addition to the list. Still something of a buzzword (do most of the people who talk about knowledge management really know what it is?), the term ‘knowledge management’ nevertheless encompasses some important concepts. It is generally accepted that in the postindustrial economies of the west, knowledge has become one of the most important resources and commodities; there is talk of ‘knowledge capital’, which joins finance capital and labour as one of the key factors of production. Learning to manage organizational knowledge, therefore, is seen as being a key benefit. (There is also the issue of managing your own, personal knowledge, which we return to below.)

Again, this may be obvious to most readers, but it is worth rehearsing these benefits and identifying where and how these (and any others) appear in the programme one is taking before moving on to look at benefit maximization.

Maximizing benefits

We have been throwing this term around for a few pages now, and it is time to determine exactly what it means:

Maximizing benefits means achieving the maximum possible during the course of an MBA programme, in terms of both personal development and career potential.

The MBA is, as mentioned above, a life-changing experience; use it to the full. More pragmatically, the MBA is likely to be expensive in terms of money, time or both; you owe it to yourself to get the greatest possible value in return for your investment.

This is, of course, easier said than done. The argument here is that the best way to maximize value is to treat the MBA as a service process, as outlined above. It follows, then, that the first step is to get to know the components of that process and how they will fit together to provide the service.

It must be emphasized again that what we are talking about here is active learning, in which the student actively seeks out source of knowledge, makes opportunitiesfor learning, and is receptive to information and knowledge from a broad range of sources. It must be emphasized too that this is not a mindset that one needs to develop solely for the MBA. Exactly this approach to learning will be called for throughout one’s subsequent career.

Another way of characterizing this concept might be to call it an entrepreneurial approach to learning. Part of the learning process is a constant, often subconcious scanning of the environment for opportunities for learning, and an assessment of knowledge gained in terms of its potential present or future usefulness. In other words, you are not just gathering knowledge for its own sake, you are treating it like a personal asset. This might be a useful concept to remember when structuring your own knowledge management programme (below).

There is a final point which needs to be made, and this concerns the individual nature of learning. One of the fascinating things about human cognition, and one of the things that separates us from computers, is its individual nature; every one of us sees things differently. The differences may be imperceptible, or they may be vast, yawning gulfs. Put ten computers in a room and input a set of data into each, and you will get the same output from each (assuming, of course, that each is loaded with the same software, and each has been installed correctly, and IT haven’t accidentally deleted a key driver from the second machine on the end). Put ten people in a room, especially ten people from different cultural, educational and technical backgrounds and ask them to describe an ordinary object, and you may get ten quite different responses. (This is one of the things that makes teamworking so fascinating; see Chapter 5.)

What this boils down to is that each learning experience is unique. How you learn is quite different from how your neighbour learns. Each of you will sit through the same lecture or work on the same case study, yet your cognitive processes will work differently, and you will take away different bits of information and analyse them to produce different kinds of knowledge. Although several hundred people may be involved in taking the same programme, attending lectures by the same faculty and writing up the same case studies, each graduate will be a unique product.

And this in turn puts personal and career goals – the motivation for taking an MBA in the first place – under scrutiny. The MBA programme offers the chance to shape your own life and career in a way that will make you unique and different, to stand out from the crowd, to be a star. It can mark you out as someone with intelligence, ability, potential. Are your goals in line with your potential? Now is the time to ask.

What do recruiters look for in an MBA?

The last two or three decades have seen something of a change in what corporate recruiters expect to find in an MBA candidate. In the 1950s and 1960s, in terms of the core benefits above, the emphasis was strongly on skills and leadership qualities; integrated thinking and global vision were less regarded, if at all. Today the situation has changed, and qualities of vision and thinking are regarded as as important, in some cases more important, than pure skills.

In part the change has occurred because of changes in the world economy, with globalization and the importance of knowledge as a commodity (referred to above) increasing in profile. But also, the MBA is no longer regarded as an automatic ticket to high office; instead, it is seen as a first step on a path of career-long learning (see Chapter 13).

Recruiters, then, are looking for potential. With this in mind, the MBA can be seen not as opportunity for great achievements, but as a chance to develop one’s own potential to achieve great things.

A resource-based view of the MBA programme

As mentioned above, the first step in determining how to maximize benefits is to determine what resources are available. Generally speaking, resources fall into four categories:

- data and information repositiories

- the business school’s faculty

- other students

- oneself

Data and information repositories

These include books, journals, CD-ROMs, websites and other sources of data and information, whether located in the business school’s library or elsewhere. This is in some ways the easiest resource to manage, as it is possible to control and order the information needed; although managing information sources, particularly those found on the Internet, can be seen as a skill in its own right. The main features of this category of resource are:

- comprehensiveness; no one knows just how many billions of words have been written and statistics compiled about manageme...