![]()

1

COLONIAL SUBURBS IN SOUTH ASIA, 1700-1850, AND THE SPACES OF MODERNITY

John Archer1

INTRODUCTION

SPACES AND PRACTICES

Suburbs and colonies, like other forms of human production, are instruments conceived to advance certain interests. Ordinarily the beneficiaries are the builders and people who may live or work there, though in many cases spaces are articulated just as intentionally to limit the interests of others. In any event, spaces of any sort that people occupy are more than mere containers or settings for human activity. The specific configuration of any space actually plays a crucial role in the formation and sustenance of the consciousness of all those who exist there. Likewise space is integral to the delineation and facilitation of the whole spectrum of relations among individuals, institutions, and social fractions (classes, castes, genders, races, etc.). Indeed the very terms and dimensions of human praxis – economic, political, moral, religious, artistic, etc. – are embedded in, and sustained by, the configuration of surrounding spaces.2

In light of such considerations, the study of colonial spaces is particularly complex – and particularly rewarding – since colonial space simultaneously sustains not only two or more distinct cultures, but also the complex array of boundaries, relations, and negotiations among them. Embedded in this array are such processes as differentiation, amalgamation, segregation, domination, exploitation, and resistance. And of particular interest in the case of colonial suburbs, the articulation of new kinds of space can sustain residents in their construction of new positionalities outside the canons of either culture – for example, the legitimation of practices outside the limits ordinarily imposed by caste or by class. The particular ways in which spaces are configured, then, are instrumental not only in the constitution, but also in the ongoing transformation of social structures and human practices.

COLONIES AND SUBURBS

Colonies and suburbs (in the sense of a locale outside the settlement proper) have existed almost since the beginning of organized settlement. For much of this time colonies and suburbs were sites of exile and alienation. Both were politically and economically dependent on the metropole. And both served the same dual functions: they were places from which to import goods that could not be produced or finished within the settlement proper, and they were places to which the unwanted could be exported (criminals, heathens, pollution). Toward the end of the seventeenth century, however, the expansion of European mercantile economies and the corresponding expansion of European bourgeoisies occasioned the refinement both of colonial settlements and of suburbs into more sophisticated and purposeful instruments for the realization of specific societal practices and relations.

Suburbs in particular, instead of being unregulated sites for practices the cities found impermissible, slowly were transformed into highly desirable, detached, clearly circumscribed, exclusively residential (and generally bourgeois) enclaves. Central to this transformation was a fundamental change in the character of the relation between suburbs and cities from hierarchical to contrapositional. The positionalities of city and suburb no longer were tied to each other by simple relations of hierarchy (e.g. one locale being intrinsically superior to the other). Rather, those positionalities came to be predicated on an array of binary oppositions (e.g. commerce/domesticity, res publica/family) which gave to each locale an integrity in part defined by negation of – not subordination to – the other. Thus I use ‘contrapositional’ to refer to the distinct, and in many respects opposed, positionalities adopted by the modern suburb and city.

Throughout the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth, the further transformation of suburbs and colonial cities – and suburbs of colonial cities – served to articulate key dimensions in which European cultures were evolving: social differentiation, economic extraction and consumption, the political redefinition of property and of possessive individualism, and the aesthetic articulation of the self. All of these dimensions are evident in the suburban growth of three colonial cities to be discussed below, Batavia, Madras, and Calcutta. But first it will be helpful to explore in more detail the role of built space in effecting social differentiation.

SOCIAL DIFFERENTIATION

It is commonly advanced as axiomatic that colonial cities as well as suburbs in general are apparatuses, even engines, of racial segregation.3 In many cases, this presumption is wrong, for it mistakes a sometime effect for a fundamental principle: race was by no means the sole or primary axis along which space was divided. In many cases, such as suburbs of Batavia or Singapore, Chinese bourgeois households were intermingled with those of Europeans. Likewise for at least the first sixty years of English settlement in Calcutta, European businesses and residences could be found spread throughout all sectors of the city; only after the battle of Plassey (1757) and subsequent intensification of economic and political pressure on the East India Company could explicit patterns of racial segregation be demarcated.

A more effective way of approaching the problem of segregation – and one that by no means discounts its widespread presence – is to approach all inhabited spaces, urban and suburban, metropolitan and colonial, as necessarily being instruments of social differentiation. They are necessarily so because human society never has functioned, and probably never could, without multiple dimensions of differentiation. The particular manner in which any culture, group, or individual configures space not only serves as a cognitive anchor of those dimensions, but also is instrumental in their facilitation and maintenance.

The flip side of difference is homogeneity. As Foucault recognized in his essay on heterotopia,4 space not only institutionalizes difference; it simultaneously provides for locales where sameness and likeness are reinforced. Differentiation, moreover, occurs in part by condensing and concentrating certain common characteristics of various social groups and fractions. As part of this process, differentiation according to such characteristics as gender, caste, race, ethnicity, occupation, religion, and citizenship comes to be institutionalized in the culture through spatial and architectural means.5

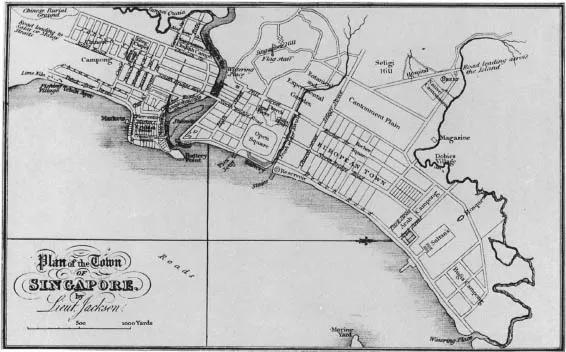

Early in the nineteenth century, belief in the efficacy of exploiting certain degrees of differentiation for economic and political purposes was fundamental to the design of colonial cities as well as suburbs. Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles’s 1822 plan for Singapore is an archetypal example of a city where particular sectors were designated for specific functions and population groups (Figure 1.1). Not long afterward John Claudius Loudon, in his epitome of suburban design, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (l838), took for granted the need for homogeneity within such sectors. Speaking of residential enclaves adjacent to metropolitan cities, he lauded those in which ‘the houses and inhabitants are all, or chiefly, of the same description and class as the house we intend to inhabit, and as ourselves’.6

In Singapore as well as in the English suburbs that mushroomed in the decades following Loudon’s treatise, as in virtually every built space, the axes of differentiation were complex and multiple. Among the axes that are relevant to the discussion of colonial cities, and metropolitan and colonial suburbs, four stand out most prominently. First are the parallel distinctions between metropolitan and peripheral, and between urban and sub urban. Both rely on the constructed notion that certain highly privileged activities (e.g. finance, legislation, ‘culture’) are located in the hub or core, while other sorts of activities that are beneath or beyond the scope of the core are relegated to the margins. Thus the original sense of ‘suburb’ in English connoted an area in which noxious, dangerous, and illicit activities occurred. Yet the eighteenth-century inversion of the term into something with very positive connotations still retained the sense of oppositionality to the core, pitting suburban aesthetic pleasure, leisure, and virtue against metropolitan politics, business, and corruption.

Second is the axis of collective identity. The different quarters that were reserved for different ethnicities in Singapore, although not wholly residential enclaves, announced a function in many respects like the suburban locales that Loudon described, where elements ‘of the same description and class’ would be concentrated. In both cases, the reservation of a specific locale for specific elements would provide for the spatial definition and support of an identity that would be seen as distinct in relation to other, differently configured portions of the city or its dependencies. The point is not only the construction of a common, homogeneous identity; it also is the differentiation of that identity from all other groups.

The third axis is the distinction of elite from non-elite. A site detached from the urban centre can be highly effective for the construction of status and prestige, since it distinguishes the site-holder as above or beyond standard constraints and rules. Examples range from ancient Roman and Italian Renaissance villas to modern-day gated enclaves. In the case of colonial cities the same axis of distinction existed, but the poles were reversed. The European metropole was the centre of fashion, learning, art, privilege, and power, characteristics embedded everywhere in its architecture, its public spaces, its interior and exterior furnishings, its theatres, the dress of its people, and so forth. The colony, then, was articulated spatially not in terms of the local idiom, but rather in terms (such as neoclassical architecture) that betokened its fealty to the centre, terms that concomitantly confirmed its provincial character. This was necessarily so: any divergence from this relation would have been inconsistent with – indeed a threat to – the enforced political and economic dependency of the colony.

Figure 1.1 ‘Plan of the Town of Singapore, by Lieut. Jackson’, 1823

Source: John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy, London, 1828 (University of Minnesota)

Finally, and by no means least, the fourth axis differentiates leisure from productive labour, a distinction that became increasingly pertinent in the eighteenth century as capital began to supplant both labour and land as an instrument for the production of wealth, status, authority, and power. Country estates from the time of ancient Rome to seventeenth-century England were, as a rule, productive working estates: they raised crops and animals, and even manufactured certain goods, for the use of the household and for export. The first decades of the eighteenth century, by contrast, saw the rise of exclusively residential villa enclaves on the outskirts of London. What distinguished these enclaves, and especially the individual estates within them, was their explicit lack of productivity. Landscapes were tailored for aesthetic contemplation, for showy luxuriance, or for sport, but above all were constructed as sites of leisure. Indeed such sites, with their manifest evocations of Arcadian plenty-without-labour, became in effect the figure in which the identity of the owner was constructed: man of leisure, unaffected by pressure of time, money, or politics, and clearly dissociated from the material constraints and pressures of the city. In the case of colonial settlements, a comparable axis obtained between colony and metropole, but once again with poles reversed: colonial cities were expected to be centres of production and extraction, revenues from which would be sent to Europe for purposes of leisure and consumption.

BATAVIA

The Dutch forcibly established Batavia (Jakarta) in 1619 as the headquarters for the Indies of the Dutch East India Company. The first century of Batavia’s existence under Dutch control also was the century during which Amsterdam enjoyed pre-eminence as a burgeoning centre of global trad...