Chapter 1

Questions of identity

Women, architecture and the Aesthetic Movement

Louise Campbell

Roger Stein, writing of the Aesthetic Movement in America, has shrewdly observed that, ‘in many respects the Aesthetic movement was a women’s movement. Women were among the leading producers of aesthetic goods, and insofar as the movement was primarily directed toward the domestic realm, they were also its chief consumers.’1 Although few women on the other side of the Atlantic attained the celebrity of the interior decorator and textile designer Candace Wheeler or her daughter Dora, designer and painter, who was portrayed by William Merritt Chase surrounded by the evidence of her artistry (the sumptuous décor and superb blue pot),2 women in Britain were also commissioning, producing and consuming aesthetic artefacts across a wide economic spectrum. They included Frances Leyland, who posed for Whistler in 1873 in a dress inspired by one in a painting by Watteau, and made especially for this occasion,3 and Carrie Footer, wife of the eponymous hero of George and Weedon Grossmith’s The Diary of a Nobody of 1892, who bought a piece of silk from Liberty’s with which to drape the photographs on the parlour mantelpiece of their home at ‘The Laurels’, Brickfield Terrace, Holloway.4 However, most of the authors who have written about the Aesthetic Movement in Britain have a different emphasis. For art historians like Robin Spencer and Lionel Lambourne, the chief protagonists of the Aesthetic Movement were the painters James McNeill Whistler and Albert Moore, the architects Edward William Godwin and Richard Norman Shaw, and the designers Walter Crane and Christopher Dresser.5 By contrast, historians of architecture and design have done considerably more to chart the networks underpinning the endeavours of artists, designers and architects, and have helped to ground this movement for design reform more securely in the specific historical and cultural context from which it sprang.6 Their work has revealed that what Mark Girouard characterised in 1977 as a generation in revolt against the tastes of their parents was also a generation which was involved in much broader areas of social change.7 One of these areas was the expansion of the activities of women beyond the domestic sphere and the negotiation of new roles for them in the years between the second Reform Bill of 1867 and the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882.8

This chapter considers two women who made use of architecture to devise for themselves a distinctive artistic and personal identity, and for whom architecture was to represent a significant aspect of their influence upon their contemporaries. Their careers indicate the diversity of the Aesthetic Movement, suggesting the existence of not one but several movements: on the one hand, elitist, hyper-refined, concerned with the cultivation of individual sensation and sensibility and signalling allegiance to an artistic avant-garde, and on the other, democratising, concerned with art education, with improving standards of design and manufacture, and with broadening access to contemporary art.9

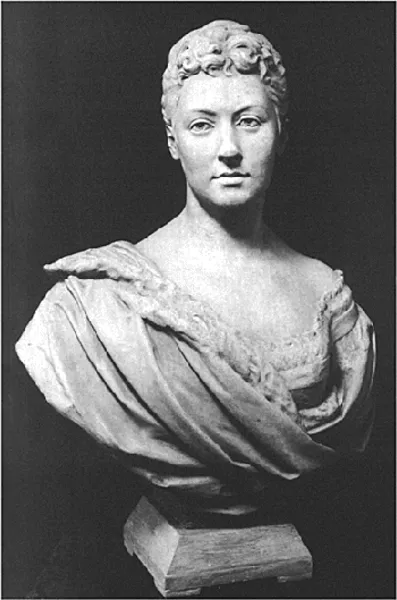

1.1 Princess Louise: Self bust, terracotta, c. 1870s National Portrait Gallery

My first example, Queen Victoria’s fourth daughter Louise (1848–1939) (Figure 1.1) demonstrates the powerful fascination which the arts exerted for wealthy Britons during the late nineteenth century; in her case, they helped to fashion a new kind of persona for a royal princess. Like all her siblings, Princess Louise had been taught how to draw and paint from a young age.10 More unusually, she also received instruction in sculpture. In the 1860s the sculptor Mary Thornycroft was commissioned to execute portraits of the Queen’s children, and, following the example of her father John Thornycroft, who had helped Prince Albert to execute a bust of his father twenty years before, she gave lessons to Louise.11 A studio was subsequently established at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight for the Princess’s use.12

In 1868 Princess Louise enrolled at the National Art Training School at South Kensington, where she was taught by the sculptor Joseph Edgar Boehm, but regular attendance there was made impossible by the demands on her time made by the Queen, to whom she had acted as social Portrait secretary following the marriage of her elder sister Helena. Louise’s own marriage in 1871 to the Marquess of Lome represented an escape from this role and allowed her to pursue her interest in art and also in women’s rights.13 Lome was well educated, cultivated and progressive, deeply interested in poetry and in art, and introduced her to a social and artistic circle much broader than that which she had previously known.14 His relatives included George and Rosalind Howard (amateur painters and patrons of the architect Philip Webb), Lord Ronald Leveson-Gower (the sculptor upon whom Oscar Wilde based the character of the dissolute Lord Henry Wotton in his novel of 1891 The Picture of Dorian Gra), the architect Eustace Balfour and his wife Frances, and Archibald and Janey Campbell, passionately interested in the theatre, and loyal patrons of Whistler.15 It was through this unconventional couple that Louise began to meet artists socially.16 The rigidity of the social distinctions which had been observed in the early Victorian period between professional people, those whose wealth derived from commerce and industry, and the upper classes and landed gentry, was beginning to break down by the 1860s. A remarkable degree of social fluidity appears to have operated in venues like the Grosvenor Gallery, opened in 1877, where the guest list for receptions and private views comprised a carefully calculated mixture of bankers and painters, actors and aristocrats, entrepreneurs and aesthetes. At the gallery, which showed work by invited artists only, an attempt was made to offer an alternative to the incoherent hanging and display conditions of the contemporary Royal Academy. The Grosvenor Gallery managed to convey the impression of both artistic and social exclusivity. Works by a given artist were grouped together, and spaced more generously than the cramped frame-to-frame hang for which the Royal Academy was notorious.17 The décor contrived to suggest not a commercial art gallery but somewhere far more select: ‘This is no public picture exhibition, but rather a patrician’s private gallery, shown by courtesy of its owner.’18 Financial backing for the Gallery came from Blanche Lindsay, a Rothschild heiress married to the owner, Sir Coutts Lindsay.19 As well as showing her sculpture at the Royal Academy in 1868, 1869 and 1874 (the first member of her family to exhibit there), and at the Old Water Colour Society, Louise exhibited both sculptures and paintings at the Grosvenor Gallery from 1878 to 1889, including an accomplished portrait of the sculptress Henrietta Montalba, a fellow student at South Kensington.20

As a Grosvenor Gallery exhibitor, Louise was introduced to the painters associated with the Aesthetic Movement and to avant-garde design. Through Janey Campbell she had met Whistler, and was one of the many visitors to the Peacock Room, the celebrated dining-room which he decorated at the Leylands’ London house at 49 Princes Gate between the summer of 1876 and the spring of 1877.21 Obliterating a pre-existing scheme featuring antique leather wallcoverings, Whistler painted the ceiling, walls and window shutters with a striking gold pattern derived from peacock plumage, painted on a ground of deep blue-green to serve as a setting for Leyland’s large collection of Nankin pottery. As he worked, Whistler held a series of receptions and press views to which journalists, friends and fellow-artists were invited. It may have been in this extraordinary setting that the Princess met Whistler’s friend and architect Edward Godwin. Such connections helped her to articulate the difference between her own tastes and way of life and that of her parents, who had warned of the folly of mixing socially with artists, or of believing that people in their own position could be professional artists.22 But for Louise, as for her contemporaries, the world of art represented an antidote to the prevalent materialism of the period and suggested the possibility of a different sort of hierarchy, in which talent and taste would be valued more highly than title or wealth.23

For their part, Whistler and Godwin cultivated their new acquaintance keenly in order to defend their work from philistine criticism and to help generate commissions among wealthy and influential patrons. In 1877 Godwin dedicated an illustrated catalogue of his designs for art furniture manufactured by the firm of William Watt to the Princess, with her permission.24 In 1878 Whistler enlisted her help over his difficulty in getting permission to build The White House, the studio-house which Godwin had designed for him in Tite Street, Chelsea, and which the ground landlord, the Metropolitan Board of Works, and its commissioner Sir James Hogg were insisting should be modified in order to fit in with the style of the fashionable Queen Anne Movement houses being constructed on nearby plots.25 Racing against time in order to complete the house, to move in and begin to take in the pupils whose fees he hoped would defray his own considerable living expenses, Whistler dreaded the prospect of further delay. He described to Godwin what happened when he told the Princess of his predicament.

She greatly sympathized—and I made a grand stroke! I said that if her Royal Highness would only drive past and say how beautiful she thought the house that of course this would put an end to the whole trouble. She laughed saying that she didn’t believe her influence was as strong as that! but afterwards said in a reflective way that “Lome knows Sir James I think…”26

It is generally claimed that the house was approved as a result of the strategic changes made by Godwin to the façade design.27 However, the Princess’s support may well have expedited matters, for Whistler presented her with a painting of the River Thames that autumn ‘as a tribute of devotion and gratitude’.28 Of more lasting significance was the gesture of endorsement which the Princess provided for Godwin as designer of tasteful and practical studio-houses, something which was further cemented by the commission which she gave Godwin in 1878 to design her a new studio in London.29

Louise’s commission to Godwin consisted of a studio without living accommodation, because she and her husband occupied an apartment in Kensington Palace. The apartment, which was decorated in 1874 by George Aitchison, Lord Leighton’s architect, provided the setting for more conventional kinds of social occasions. The colour scheme consisted of:

green woodwork and green and red walls in the ante-room; brown woodwork and dull pink walls in the small dining-room; green woodwork and gold walls in the drawing-room; red woodwork and gold walls in the large dining-room.30

Furnishings apparently included green-stained armchairs designed by Richard Norman Shaw.31 The studio, by contrast, was the place for work and for informal socialising, for ‘laughter and skylarking’.32 Godwin provided the following account of the design process:

a builder had volunteered to put up a studio for about £800. The Princess Louise thought this was rather too much for a simple...