![]()

Chapter 1

Theoretical background

T.R. Miles

THE NATURE OF DYSLEXIA

Although the manifestations of dyslexia were identified more than a hundred years ago, it is only in the last few decades that there has been recognition of the condition on any large scale. It is perhaps helpful to think of dyslexia as a family of manifestations: these may vary from one individual to another, but in all cases there is an identifiable pattern, and it is this pattern which, despite the differences between individuals, justifies the use of the same diagnostic label, ‘dyslexic’.

As far as the acquisition of literacy skills is concerned, there can be no denying that dyslexia is a handicap. Most dyslexics are late in learning to read and have considerable difficulty in learning to spell. The spell check, though useful, is not an infallible guide — for instance it will not correct ‘peace’ into piece nor ‘never the less’ into nevertheless. Much can be achieved by appropriate tuition, but the problems do not totally disappear. In particular most dyslexics remain slow readers, and although some speeding up is possible, any task which calls for the processing of symbolic material at speed is likely to cause them difficulty. In most cases, too, there will be problems with remembering times, dates, appointments, etc., and for some it is difficult to remember and reproduce items in a series such as the months of the year.

Today, however, it has become widely recognised that dyslexics should be encouraged to ‘think positive’ and not to underestimate their abilities. Some of them can be extremely creative and many are gifted in art, architecture, engineering and the like.

This imbalance of skills is reflected in the way in which dyslexics perform at mathematics. Mathematics calls for many different kinds of ability. In general, dyslexics tend to be slow at certain basic aspects of mathematics — learning multiplication tables, adding up columns of figures, etc. — but once they have understood the symbols they can show profound understanding and may be extremely creative. It is therefore crucially important to distinguish the dyslexic child from the slow learning child, whose educational needs are very different.

Readers wishing for an overview of the field, with information as to where more detailed evidence can be found, may like to consult Miles and Miles (1999). For a series of papers reflecting some of the areas currently being researched we recommend Fawcett and Nicolson (eds) (2001). For reports of the many different stresses experienced by dyslexics, readers may like to consult Miles (ed.) (2004).

It is now established beyond reasonable doubt — something which had earlier been suspected but was supported only by circumstantial evidence — that the manifestations of dyslexia have a physical (constitutional) basis. This was confirmed in the 1980s by post-mortem examination of the brains of those known to have been dyslexic in their lifetime, and, more recently, by ever-more sophisticated brain-scan techniques.

Awareness that dyslexia has a physical basis is important for teachers for a number of reasons. In particular, if one knows that a child is struggling to compensate for a constitutionally caused weakness, one will be much more hesitant to accuse that child of laziness or lack of effort.

The most widely accepted explanation of the manifestations of dyslexia, though by common consent it does not explain all of them, is that dyslexics have difficulty with phonology — that is, with the remembering and ordering of speech sounds. It follows that — at least in the case of the English language — letter-sound correspondences need to be taught slowly and systematically; and to aid memorising the teaching has to be multisensory, that is, to involve as many senses as possible. Thus the pupil is encouraged to look carefully at what he has written, to listen carefully to the sound of the word (and note the number of syllables), to pay attention to his mouth movements in saying the word and to his hand movements in writing it. As will be seen later in this book, a multisensory approach is also essential in teaching dyslexics to understand mathematics.1

SOME INFORMAL OBSERVATIONS

I begin this section by reporting some of the observations made by myself and others over the years. My central aim is to illustrate the incongruities found in the performance of dyslexics in the area of mathematics; some of them can have all sorts of ingenious and creative ideas, and yet have extreme difficulty over learning multiplication tables and other basic number facts. Some of them in fact show their ingenuity in finding ‘ways round’ — compensatory strategies — when knowledge of the required number fact is not automatic.

Problems over left and right

I tested Joan for suspected dyslexia. She was aged 16, and was hoping to go to university. She showed many indicators of dyslexia on the Bangor Dyslexia Test (Miles 1982, 1997), including an incongruous failure at ‘three digits reversed’ — when asked to say ‘3–7–1’ backwards she said ‘1–3–7’. Yet on the Terman Merrill intelligence test she passed three items out of four at Superior Adult I and three items out of four at Superior Adult II. My colleague, Barbara Large, reported to me that during subsequent tuition she was given the sums: 103−52 and 36−27. She produced the following:

Her reasoning was: ‘Five from one won't go, so borrow ten and turn the one into eleven — five from eleven leaves six. Pay back the one so that the middle figure in the 103 becomes nine — two from nine leaves seven. Pay back again so that the three in the 103 becomes two, and subtract zero from it — so six-seven-two’.

Joan had clearly learned something about ‘borrowing’ and ‘paying back’, but with no real understanding, and no awareness of the approximate order of magnitude of the correct answer. One of her basic mistakes was to start the subtraction sum on the left and not on the right — and we know that uncertainty over left and right is very common among dyslexics.

In the next sum she tried to adopt similar procedures and was completely defeated.

What she wrote was:

She could take two from three but how was she to take seven from six?

Any dyslexic who is uncertain over left and right has to come to terms with the fact that in three of the four arithmetical operations (multiplication, addition and subtraction) one has to start on the right, whereas in the case of the fourth (division) one has to start on the left.

Farnham-Diggory (1978) also cites a case where confusion between left and right led to problems. Although ‘he solved mental problems by clever regrouping strategies.… Ralph's written compositions were seriously in error. He lined up numbers from left to right, as in

He did not know how to carry; for example, given

he began to add from the left, doing 1 + 1 =2. Next he did 9 + 6 = 15, which would have given him

which would have given him 215, but somehow — it is not clear how — he realised that 215 contained too many digits. His solution was simply to ignore the 5! This then gave him an answer of 21’.

I came across an interesting example of how left—right confusion can affect one's judgement of number. This goes back to, the days when petrol was 74p per gallon. I was told by the parents of a 15-year-old that on the journey to my assessment he had looked towards a petrol pump and said: ‘Gosh! That petrol's cheap — only 47p’.

Compensatory strategies

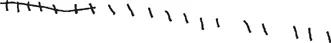

Some of the remarkable behaviour which I have observed in dyslexics seems to be the consequence of their trying to devise their own compensatory strategies. If one does not have the number facts readily available there are still ways of compensating. My first example is that of a girl aged 10 who, when asked what was ‘19 take away 7’, produced the response shown in Figure 1.1.

Her procedure was to make 19 marks on the paper, then separate out seven of them, and then count up the remainder, which gave her the correct

Figure 1.1 Response to 19 take away 7

answer, 12. Her procedure is interesting because most children aged 10 would have been able to give the answer ‘in one’.

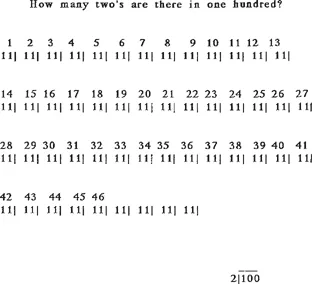

In a school exercise book belonging to a dyslexic boy whom I will call John (I have no record of his exact age), I found as shown in Figure 1.2.

I do not know his exact strategy, but I suspect he may have drawn the dividing lines after each group of two marks and then written in the numbers. Only when he had got as far as 46 was he able to count ahead and, presumably, come up with the answer 50. The figures

in the bottom right corner may have been an attempt to oblige the teacher by doing as he was told, but why his teacher had asked him to start the sum in this way was clearly lost on him.

Figure 1.2 How many two's are there in one hundred?

John had made a valiant effort, which one cannot but admire. However, although in general I am reluctant to interfere when dyslexics produce their own ingenious ways of doing things, in John's case I would have sounded him as to whether he was interested in a less time consuming and more labour saving way of arriving at the answer. If he knew that there are five twos in ten and that 20 is 10 × 2, 30 is 10 × 3, etc. he might have arrived at the answer, 50, more quickly and with less effort.

It is my experience that many dyslexic children need to use marks on paper or concrete aids at an age where most of their non-dyslexic peers find this unnecessary. It seems as though in many cases the memorising of number facts does not come easily or automatically. It also makes sense to suppose that where there are regularities in the number system such memorising is easier.

Many of the contributors to this book will be pointing out the usefulness of algorithms — that is, rules of procedure — in those situations where one does not have a number fact immediately available. My suggestion is that dyslexics who resort to marks on paper or to counting on their fingers at an age when most of their peers find this unnecessary, do so because they need an algorithm — and there is one unfailing algorithm that they can use, namely that the numbers go up in ones!

I owe to my colleague, Anne Henderson, the following remarkable example of a compensatory strategy.

David was asked to multiply 532 by 8. The following is a record of his comments:

Think of 8 as 10 and of 532 as 500. 500 times 10 is 5000. But this is two lots of 500 too big. 500 doubled is 1000; 5000−1000 is 4000. Think of 32 as 30 — I don't know my 8 × table — only my 5 × table, so 5 × 8 is 40; 10 × 8 is 40 doubled = 80.I need three lots of 10s in 30, 80 doubled is 160 = 20 × 8, therefore 160 + 80 = 30 × 8 = 240. 8 doubled is 16. So the answer is 4000 + 240 + 16, which is 4256.

This answer is correct! — and, given that he did not know his 8× table, is a remarkable tribute to David's ingenuity.

Losing track

Another characteristic of dyslexics (to which we shall be returning in the next section) is that they are liable to ‘lose track’ of where they are; for example, in reciting times tables they are liable to produce such questions as, ‘Was it six sevens I was up to?’. A likely explanation seems to be that, in comparison with non-dyslexics their memories are more likely to become overloaded. My colleague, Ann Cooke, told me of a boy who, when the task involved holding in mind several things at once, commented ‘I haven't got enough think left’. Here is an account of a dyslexic businessman who experienced this difficulty — and he showed me how he had devised a strategy for getting round it.

A dyslexic businessman who was in the meat trade continually found himself having to add up columns of figures. On one occasion, the requirement was to add 7, 3, 12, 22, 43 and 37. Instead of wri...