- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Material Concerns offers new perspectives on key environmental issues - pollution prevention, ecological economics, limits to sustainability, consumer behaviour and government policy. The first non-technical introduction to preventative environmental management, Material Concerns offers realistic prospects for improving the quality of life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Material Concerns by Tim Jackson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

LIVING IN A MATERIAL WORLD

Rough guide to a lonely planet

INTRODUCTION

We are living in a material world. To say this is not just to say that the affluent consumer societies of the Western world are excessively materialistic. It is not just to claim that our priorities and our values have become increasingly embedded in the ownership of material possessions. These claims may be true, and at a later stage of this book, I shall examine that possibility further. But there is something much more basic involved in saying that we live in a material world.

Many of our most vital needs are essentially material ones: food, water, shelter, clothing and fuel. We survive as human beings by cultivating crops to convert to foodstuffs, manufacturing textiles to turn into clothing, excavating clay, sand and rock to build homes for shelter, mining coal and oil and gas to provide us with warmth, light and mobility, and extracting metals from ores to make the machinery and appliances we need to do all this.

In fact, there is a sense in which life itself is a fundamentally material concern. All biological organisms require energy to maintain life. Some organisms (green plants) are able to obtain this life energy directly from the sun. Many organisms (including human beings) have to obtain life energy by feeding on other material organisms. The process of digestion converts food into faeces, and releases energy. This energy allows us to maintain our complex biological structure, to forage for food, to reproduce the species, and to defend ourselves against predators. Without these material inputs and outputs we simply could not survive. So to say that we are living in a material world is to say something fundamental about the interaction between human society and its environment.

These days, of course, the scale and complexity of our material interactions are vastly increased over those of earlier societies, and over those of other biological organisms. The material requirements of ‘advanced’ industrial societies extend far beyond the survival needs of food, warmth and shelter. There are now growing demands for a wide range of material goods from aerosols to aeroplanes, cosmetics to computers, and vinyls to videos.

In spite of this complexity, there are two aspects of the industrial economy which relate it directly to other more ‘primitive’ societies, and indeed to the social organisation of other biological species. The first aspect is the common aim of survival. The second is the common set of physical laws which govern behaviour in all material systems. This common physical basis is so critical to the interaction between the human species and its environment that we must gain some understanding of it, right at the outset, before we can proceed with the investigations. The aim of this first chapter is to provide that understanding.

A THUMBNAIL SKETCH OF THE INDUSTRIAL ECONOMY

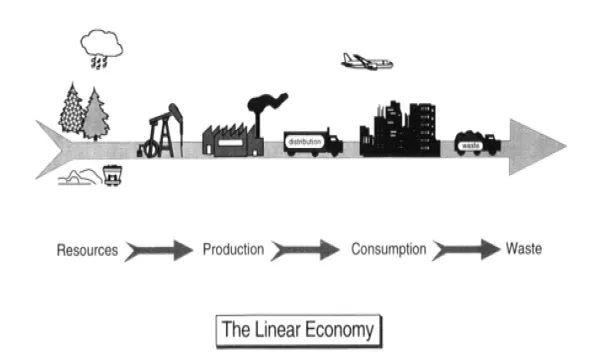

A simplified picture (Figure 1) will help to place some elementary structure on the complexity of the industrial economy. It is clear from the diagram that there is a more or less linear flow of materials through the system. Material resources extracted from the environment at one end of this flow are processed in various ways to provide goods and services within the economy, before flowing out of the economic system back into the environment as emissions and wastes.

There is an important distinction between two different types of resource inputs. The first type of resource is called renewable resources. These resources are provided on a continuous basis by the flow of certain kinds of materials and energy through the environment in well-established cycles. Renewable resources include many timber and forest products and agricultural products of various kinds.

Figure 1 Material dimensions of the industrial economy

The second type of resource is non-renewable. We gain access to these resources only by depleting finite stocks of materials which have accumulated in various places in the environment sometimes over many thousands of years. The industrial economy now relies heavily on a number of non-renewable resources, including coal and petroleum, metallic minerals (iron, copper, aluminium, zinc, cadmium, mercury and lead, for instance), and various important mineral rocks such as phosphate, limestone and slate.1

Resource inputs (of both types) are then subject to various stages of processing and distribution in order to provide the goods and services demanded in the economy. The first stage of processing—often called primary processing—involves separating pure materials from the mixed form in which they are usually extracted from the environment. Physical, chemical and thermal separation and recombination processes convert the raw materials into finished materials such as fuels, refined metals and alloys, and industrial chemicals. Examples of such processes are the roasting and smelting of metal ores to separate metal from rock, the ‘cracking’ of crude petroleum to obtain specific oil derivatives, and the threshing of grain to separate wheat from chaff.

Materials purified in the primary sector are destined for the manufacturing industries, where materials are transformed into finished products. These industries are sometimes called the secondary sector of the economy. They include the textiles industries, the food-processing industries, the pharmaceuticals and cosmetics industries, the automotive industry, and the electronics industry.

Finished products from the secondary sector are then transported and distributed to the consumer. Most of the products are destined for another part of the industrial economy, sometimes called the tertiary sector. Part of this sector consists of retail trades which distribute the finished products to household consumers. The rest of the sector provides different kinds of services such as health, education, transport, household utilities, banking and communications.2 Together with households, the tertiary sector is the main ‘consumer’ of the material products of the industrial economy. In addition, some of the products of the primary and secondary sectors are consumed within those sectors. For instance, the mining industry uses drilling and extraction machinery, the electricity supply industry needs combustion and generation technology and so on.

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS

When it comes to environmental impacts, the primary sector activities tend to be intrinsically ‘dirtier’ than secondary sector activities. The reason for this is quite straightforward. The role of primary sector processes is to separate and purify certain desired materials from a mixture of materials extracted from the environment. This means two things. First, the separation of pure materials from a mixture requires the input of energy. Second, the process of purification implies that some materials from the mixture are unwanted and must be discarded as wastes.

Consider the processing of pure copper metal from ores. To start with, excavating mineral ores requires the stripping of topsoils and rocks. This overburden can sometimes be several times greater than the weight of ore excavated. Next, the concentration of copper in copper ores is typically as low as 0.5 per cent to 2 per cent by weight. This means that for each kilogram of copper metal, between 50 and 200 kilograms of residue may be created. Finally, extracting copper from copper ore requires an energy input of between 50 and 100 megajoules3 per kilogram of finished copper.4 This separation energy is almost always provided by burning fossil fuels. And the combustion of fossil fuels is responsible for some of the most pressing environmental problems we face: global warming, acid rain, local air pollution, and the need to dispose of contaminated ashes and residues.

By contrast, the secondary sector activities tend to be less energy-intensive and often less liable to polluting residues, precisely because they are dealing with purer inputs. This does not mean, however, that they are pollution free. We shall see later in this chapter that any industrial process must inevitably generate wastes. Secondary sector industries are no exception.

The distribution and transportation of goods from manufacturers to retailers and then to consumers also gives rise to environmental impacts. In fact, the development of the industrial economy over the last fifty years has witnessed two trends in the development of transport requirements with specific environmental implications. In the first place, there has been a tendency towards centralisation—both of production facilities and of distribution outlets. Second, there has been an increasing globalisation of world trade. These two facets of the modern industrial economy impose special demands on the transport infrastructure. Goods must be transported often thousands of miles from the point of production to the point of consumption. Consumers often travel increasing distances from home to the point of sale. The increased demand for transportation has led to increased vehicle emissions, the loss of land to highways, railways, ports and airports, and the nuisance and public health effects which these developments bring with them.

The tertiary sector does not itself manufacture material products. Consequently, it does not generate production wastes. But we should not be seduced into believing that its activities are inherently clean. Most importantly, this sector consumes material products. And these products must be provided by the primary and secondary manufacturing industries. So in a sense, it is the demands of the tertiary sector which are partly responsible for the pollution from the primary and secondary sectors.

A similar thing can be said about households. In fact, householders create both the demand for material goods and the demand for services provided and distributed by the tertiary sector. This demand for goods and services is really the engine which is driving the industrial economy. It is, if you like, the root cause of the environmental impacts from the primary, secondary and tertiary industrial sectors and much of the transportation network. And this same demand generates increasing quantities of household and consumer waste: products and materials which are thrown away once they have reached the end of their useful life.

Some kinds of products are inherently dissipative in nature. Using them means consuming them in such a way that materials become widely dispersed into the environment. Some obvious examples of this kind of dissipative consumption are the combustion of fossil fuels, the use of domestic pharmaceuticals such as soaps, washing powders, detergents and bleaches, and the spreading of chemical fertilisers, herbicides, insecticides and fungicides. Some slightly less obvious examples include the use of lead as an additive in motor fuels, the use of zinc additives in rubber, which are released when tyres wear away, and the use of cadmium in metal plating. Other products are not inherently dissipated in this way. But the pattern of consumption of most products leads to their wide geographical dispersal throughout the economy. Disposal of these products at the end of their lives also gives rise to the dissipation of materials into the environment.

Certainly, therefore, we cannot exonerate the consumer from the environmental impacts of the industrial society. Neither can we expect to clean up our environmental act just by looking at the damaging emissions from the primary and the secondary sector industrial processes. Rather we must place the consumer at the centre of the complex materials network which comprises the industrial economy. And we must place on the consumer at least some of the responsibility for making the economy sustainable.

A COMMON PHYSICAL BASIS FOR MATERIAL SYSTEMS

Despite the complexity of the modern industrial society, its underlying rationale could be said to be the same as the underlying rationale of all societies throughout the ages: to provide for the needs of the men, women and children who constitute that society. Some of these needs are the basic material needs of all biological organisms: food, water and shelter. So we could even argue that part of the rationale for our complex industrial economies is the same as that which governs the behaviour of every other biological species: survival.

It is clear of course that the goals of the industrial society extend considerably beyond mere survival. In poorer countries, survival is often still a luxury. But in the affluent developed nations of the industrial world, people’s expectations and goals reach further than mere subsistence. Later in this book, I will return to consider the question of these more complex goals and needs. Here I want to concentrate on the common physical basis which all biological species share alike.

So let us start by looking at the physical laws which govern our behaviour in the industrial economy. These laws are the same fundamental laws as those which govern energy and material transformations in all physical systems. In particular, they govern material activities in the ecological systems (or ecosystems) which have successfully sustained a wide variety of species for many thousands of years. So whatever the differences which now distinguish human societies from ecosystems, we can certainly learn from the basic ground rules which determine our common physical inheritance.

Two of the most important of these ground rules come from the physical theory known as thermodynamics (which means literally ‘the theory of the movement or flow of heat’). Each industrial process and each economic activity involves the transformation of materials and energy from one form to another. Thermodynamics provides very specific rules and limits which govern these transformations. This theory was developed right at the start of the industrial revolution, primarily to describe the behaviour and optimise the performance of the early heat engines which paved the way for rapid technological progress (see Chapter 2). So it is perhaps particularly appropriate that we should pay careful attention to that theory in the early stages of this investigation.

CONSERVATION LAWS

Amongst the most important of these physical rules are three important conservation laws. The first of these is the law of conservation of energy (also known as the first law of thermodynamics). Energy exists in a number of different forms—including gravitational energy, chemical energy, electrical energy, heat, light and motion—all measurable in the same energy units (called joules). These different forms of energy are continually being transformed from one type to another. For instance, the energy of motion is transformed into heat when we apply brakes to a moving car. Chemical energy is transformed to heat through combustion. In fact, it is these energy transformations that allow us to carry out useful work, and provide goods and services in the industrial economy.

The first law of thermodynamics (the law of conservation of energy) tells us that energy is neither created nor destroyed during these transformations. The total energy input always matches the total energy output. For example, when coal is burned, chemical energy is transformed into thermal energy. But the heat output is no more and no less than the energy stored in the chemical bonds of the coal to start with.

A second important conservation law is the law of conservation of mass during material transformations.5 This law tells us that the total mass of the material inputs to a transformation process is equal to the total mass of the material outputs. It points out that, if we require certain material products, we must find the equivalent material resources to provide for those products. But it also asserts that all of the material resources which we exploit and transform through human activities must end up somewhere—if not...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of boxes

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Living In A Material World: Rough guide to a lonely planet

- 2 Material Transitions: The birth of the industrial economy

- 3 Farewell To Love Canal: From industrial afterthought to environmental foresight

- 4 A Stitch In Time: The principles of prevention

- 5 Easy Virtues: Saving money through pollution prevention

- 6 Persistent Vices: Understanding resistance to change

- 7 Back To The Future: Reinventing the service economy

- 8 Negotiating Change: Dematerialisation and the profit motive

- 9 Growth In Crisis: Untangling the logic of wealth

- 10 Beyond Material Concerns: Regaining quality of life

- Notes

- Select bibliography

- Index