Chapter 1

Introduction

Jan Vissers and Roger Beech

DEFINING HEALTH OM

The term operations management refers to the planning and control of the processes that transform inputs into outputs. This definition also applies to health OM. Consider the individual doctor/patient consultation.The input to the consultation process is a patient with a request for health care. The output of the consultation process might be that the patient is diagnosed, referred to a further service, or cured.The resources that have to be managed to transform inputs into outputs are those associated with the care provided by the individual doctor: for example, their time and any diagnostic or therapeutic services that they use.

In this illustration the role of the health OM process was to ensure that adequate resources were in place to provide an ‘acceptable’ service for the patient. Hence, health OM focuses on the individual provider that produces a health service and on the tasks involved to produce this service.

In the above illustration the individual provider was a doctor. However, the ‘individual’ provider might be, for example, a hospital department (e.g. an X-ray department), a hospital, or a network of hospital and community-based services (e.g. services for the acute care and rehabilitation of patients who have suffered a stroke). At each level both the scale and scope of the resources to be planned and controlled increase, as does the complexity of the OM task.

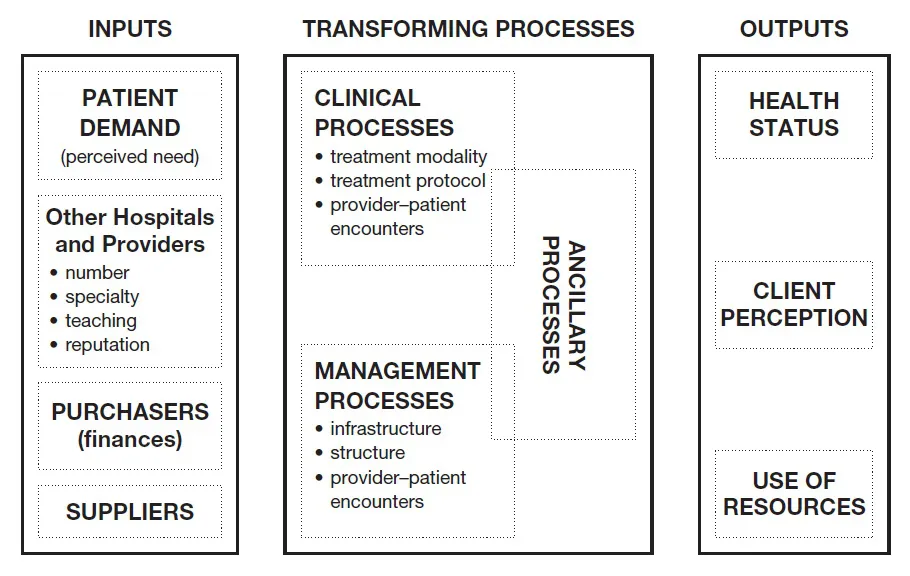

Figure 1.1 presents an example of a health OM view of an individual hospital provider, adapted from a meta-process model of a health care delivery system described by Roth (1993).The agenda for health OM is covered by the central box.

The central function of the hospital is to provide patient care. Hence, patient demand for care is the key input that influences the planning and control of the resources required to transform inputs into outputs. However, as Figure 1.1 illustrates, other ‘inputs’ influence both the types and levels of patient demand and the ways in which the hospital delivers care. These other ‘inputs’ include the overall level of finance available to provide care, the availability of goods from suppliers, and the nature and actions of other hospitals.

Figure 1.1 Meta-process model of a health care delivery system. Adapted from Roth (1993)

Figure 1.1 highlights three generic processes for transforming inputs into outputs: clinical, management and ancillary. Clinical processes are probably the most important as they are directly associated with the planning and control of those resources used for the diagnosis and treatment of patients. However, management processes are needed to support the clinical processes. These management processes include those for organising the payment of staff and for purchasing goods from suppliers. Finally, ancillary processes are needed to support the general functioning of the hospital.These processes include the organisation of services for cleaning hospital wards and departments and for maintaining hospital equipment.

The resources to be planned and controlled within each of these processes include staff (e.g. doctors, nurses), materials (e.g. drugs, prostheses), and equipment (e.g. X-ray machines, buildings). Inadequate planning and control of resources within any of the processes can have an impact on the others. For example, deficiencies in the management processes for ordering materials may affect the quality of care that can be delivered by the clinical processes (e.g. a shortage of equipment to support care at home may lead to delays in patient discharge from hospital). Similarly, if services for the cleaning of hospital wards are inadequate, the potential for hospital acquired infections will be increased, as will the likelihood of subsequent ward closures.

Hence, when planning and controlling the resources that they use, an ‘individual’ provider must also consider the ways in which their actions might impinge upon other ‘individual’ providers, for example other hospital or community-based departments. In this sense, their actions represent ‘inputs’ to other processes for transforming inputs into outputs.

Finally, Figure 1.1 illustrates the outputs of the OM processes that must be monitored. Health status markers (e.g. mortality rates, levels of morbidity and disability) are relevant to the success with which clinical processes are transforming inputs into outputs, as are measures of client perception/satisfaction where the client (and/or their family) is the patient. In addition, the client of a process might also be a hospital doctor who requires a service from a diagnostic department or a hospital manager who requires details of patient activity levels from doctors. Similarly, ‘resource’ performance output measures are relevant to all three generic processes as they are needed to monitor the efficiency (e.g. patient lengths of stay, response times of ancillary support services) and effectiveness (e.g. use of ‘appropriate’ or ‘modern’ procedures) with which resources have been used to transform inputs into outputs.

Again, there are relationships and potential conflicts between the different types of output. For example, measures to increase patient satisfaction by reducing patient waiting times might require additional investment and mean that the hospital is unable to achieve its budgetary targets. Similarly, budgetary pressures may mean that a hospital is unable to invest in all of those services that are known to be effective in improving health status: examples might include expensive treatments for rare conditions. Hence, in its attempts to ensure that there is an effective and efficient organisation of the delivery of services, the role of health OM is to achieve an ‘acceptable’ balance between different types of output.

Having illustrated the nature of health OM it is now possible to offer a definition of health OM:

Health OM can be defined as the analysis, design, planning, and control of all of the steps necessary to provide a service for a client.

CONTEXT OF HEALTH OM

This section discusses the context of health OM decision making: drivers for change and factors that influence decision making. The previous section demonstrated that the system of ‘inputs’,‘transforming processes’ and ‘outputs’ is subject to its own internal dynamics and influences. Efforts to improve the outputs from one process might have an impact on the inputs and outputs of others. Here, we will discuss some of the key ‘external’ factors, and additional ‘internal’ factors, that influence health OM decision making. Again, for the purposes of illustration, we will take the perspective of an individual hospital provider.

Probably the main external factor that affects the behaviour of individual providers is the overall health care system setting in which they function, for example, market and ‘for profit’, national health system or government regulated. In a ‘for profit’ setting, the emphasis for providers is on profit maximisation. As a result, providers will want to maximise the number of patients whom they can treat at ‘acceptable’ standards of quality but at ‘minimum’ costs per case. The market environment, therefore, creates the incentives for providers to ensure that the processes for transforming inputs into outputs are functioning in an effective and efficient way. Providers must continually review and invest in their transforming processes as a means of maintaining their market share, attracting new patients or reducing costs. For example, the market creates the incentives for providers to invest in new health care technologies in order to either attract more patients or reduce costs per case.

In a national health system or government regulated system, providers are budgeted by the contracts annually arranged with purchasers (government related bodies or insurance organisations). In such a system the main incentive for providers is to ensure that budgetary targets are not exceeded. Hence, providers need to invest in mechanisms for monitoring the use of key resource areas such as the use of beds and theatres. Beyond the need to ensure that ‘cost’ performance targets are achieved, relative to the market environment, providers probably have lower incentives to continually review and update transforming processes or to ensure that other ‘output’ measures, such as client perception are ‘satisfactory’.

However, this situation is changing and, in the absence of market incentives, regulation is being used as a vehicle for change. For example, in the National Health Service (NHS) of the United Kingdom (UK), National Service Frameworks are being developed for key disease areas (e.g. diabetes) or patient groups (e.g. older people). These frameworks specify the types of services that should be available for patient care: hence, they have a direct influence on clinical processes.The NHS of the UK is also setting performance or ‘output’ targets for providers, for example, maximum waiting times for an outpatient appointment or an elective procedure. Again, to ensure that such targets are met, providers will need to review and modify their processes for transforming inputs into outputs.

In Europe, government regulated health care systems are still dominant but gradually more market incentives are being introduced. In the US, although health care is shaped as a market system, the level of regulation is increasing through developments such as the development of Health Maintenance Organisations.

Beyond the health care system, and the actions of governments, other external factors are affecting the context in which health OM decisions are made. For example, most western countries are experiencing changes in the demographic mix of their populations such that there is an increasing proportion of older people. Both the scale and nature of hospital resources (and those in other settings) will need to be adjusted to meet this demographic change. For example, the NHS of the UK is currently expanding its services for home-based care as an alternative to hospital care.

In addition, advances in medical technology (for example, new drugs and other forms of treatment) are either changing or expanding the options that are available for patient care. Providers will need to decide if and how they should respond to these advances. Again, government regulation is likely to be used as a vehicle for change.

Finally, via the internet and other outlets of the media, patient knowledge of health care treatments and expectations of heath care providers are increasing. Providers are having to adjust their care processes to address this change in consumer expectations.

Up until now, this discussion of the context of health OM has focused on external factors that affect the environment in which decisions are made. In comparison to other service or manufacturing organisations, the internal environment for decision making is in itself unusual.

Often, the roles and responsibilities of those involved in decision making are either not very clearly defined or are overlapping. Health care management often takes the form of dual management, in which clinical professionals share management responsibilities with administrative staff and business managers. Finding out who is actually managing the system can therefore be a real issue in health care organisations.

In addition, health care management decision making often takes the form of finding consensus among the different actors involved: managers, medical professionals, nursing staff, paramedical disciplines, administrative staff. These actors often have different interests along the dividing lines of quality versus costs or effectiveness versus efficiency. As health care does not have the possibility of defining profit as an overall objective, it is often difficult to find the right trade-off between these two perspectives of managing organisations.

Hence, there is a range of ‘external’ and ‘internal’ factors and challenges that influence health OM decision making.This book presents a scientific body of knowledge and reflection to support the planning and control of health care processes.

RELATED FIELDS

Health OM activities are complemented by and related to other areas of ‘management’ activity that focus on the core processes of the organisation. These other areas include:

- quality management, which aims to improve and maintain the quality of services delivered by processes;

- performance management, which concentrates on measuring and monitoring the performance of the organisation in terms of the outcomes of processes;

- information management, which concentrates on the development of tools for providing and handling information about processes; and

- operational research, which offers analytical techniques and approaches that can be used to investigate and improve processes.

Often the boundaries between health OM and these other areas of ‘management’ might seem somewhat ‘fuzzy’. However, it could be argued that health OM creates the broad agenda that is then addressed, in part, by these other fields of management.

OUTLINE OF THE BOOK

This book is the first to focus explicitly on health OM and its development. Chapters 2–6 therefore offer conceptual contributions to the development of health OM theories and techniques.The main body of the book then consists of a number of case studies that illustrate health OM at work in health care settings. The concluding chapter of the book discusses future challenges and further areas of development for health OM.

Scientific interest in the development of theories and techniques to support OM originated in the manufacturing and service environment. The supply of health care is often seen as a special type of service industry. Hence, many health care researchers and managers have turned to OM literature from the industrial and service sectors when seeking answers to the many problems faced in delivering health services. In chapter 2, Will Bertrand and Guus de Vries offer a critical discussion of key theories and techniques that originated in industrial and service sectors and the ways in which they might contribute to health OM. It will be demonstrated that many theories and techniques developed in industrial and service sectors are not directly applicable to health OM, but that nevertheless the underlying principles may still hold and need to be translated to health care.

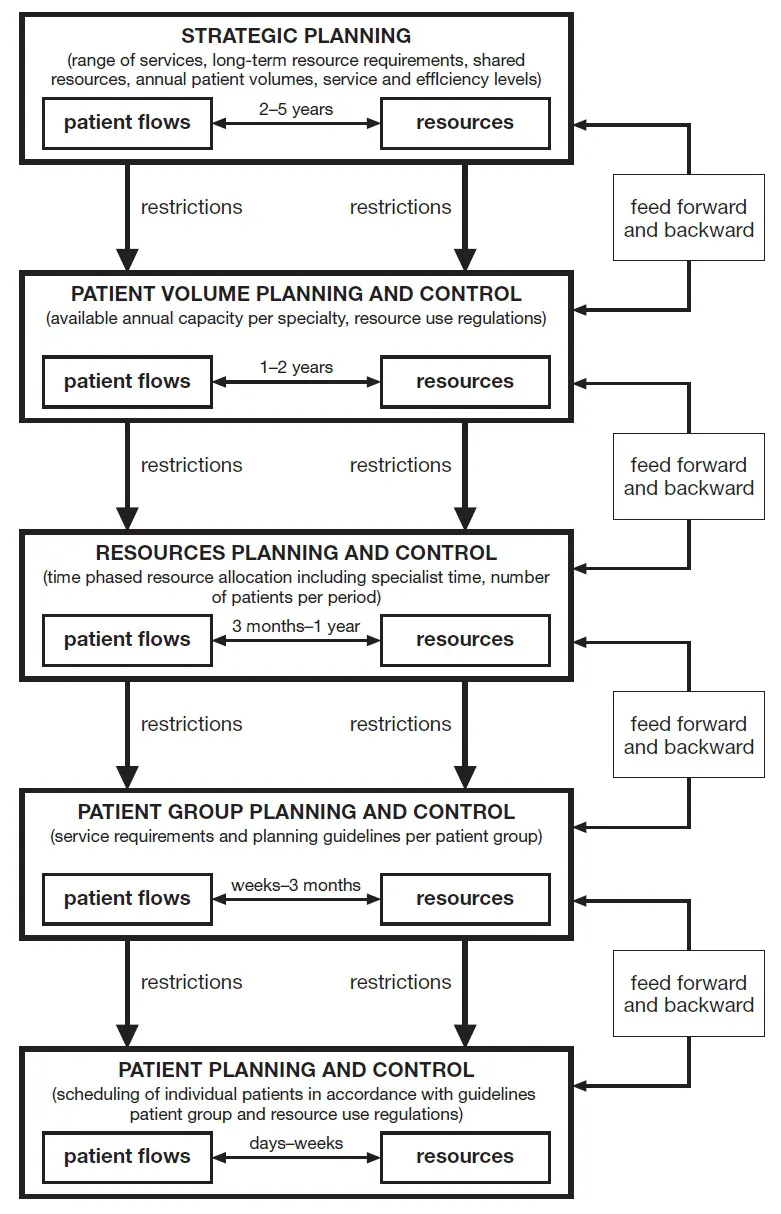

Health OM, therefore, requires a specific approach. Chapters 3–6 develop a conceptual framework for positioning health OM theories and techniques. An overview of this framework is given in Figure 1.2.

Earlier the health OM process was considered from the perspective of an ‘individual’ provider. The potential breadth of the health OM task was indicated by the fact that the ‘individual’ provider might be, for example, a doctor, a hospital department, a hospital or a network of hospital and community based services. Figure 1.2 illustrates the potential depth, or differing aspects, of the health OM agenda of responsibilities. Again, for the purposes of illustration, this agenda will be discussed from the perspective of an individual hospital.

Figure 1.2 Conceptual framework of health OM planning and control processes.

Strategic planning decisions create the long-term vision of the hospital and the types of services that it should provide. However, this vision then needs to be implemented and sustained. This is the function of health OM processes: turning strategic visions and directions into reality.

‘Patient volume planning and control’ represents the start of the process of deciding how best to transform ‘inputs’ into ‘outputs’. This represents an initial check that the hospital has the correct types and amounts of services (or transforming processes) in place to meet the needs of the patients whom it plans to treat.This check will need to be remade at more detailed levels of planning further down the framework.The concepts used for elaborating the various aspects of the health OM agenda of responsibilities are discussed in chapter 3.

The process of checking that the hospital has the correct types of services in place is described in terms of an assessment of the types of ‘units’ or departments required, the types of ‘resources’ that they will use and the types of ‘operations’ or activities that they will undertake. For example, hospital admissions are cared for on wards (units) that require nursing staff (resources) who provide general medical care (operations). Similarly, surgical patients are treated in operating theatres (units) where surgeons (resources) undertake surgical procedures (operations).

Checking that the hospital has the correct amount of services in place is more complex and requires an understanding of the relationships between patients, operations and resources. Chapter 3 begins this process of understanding by introducing the concepts of ‘unit’ and ‘chain’ logistics.

Units undertake similar types of operations for (usually) different types of patient: for example, operating theatres are used by patients requiring orthopaedic procedures, urological procedures, general surgical procedures etc. Unit logistics aims to ensure that the resources used by a unit are allocated in an appropriate and efficient way. Hence patients might be treated in ‘batches’, for example, general surgery theatre sessions on Monday and Wednesday afternoons. Alternatively, patient access to resources might be prioritised in a way that smoothes peaks and troughs in terms of demands for resources: for example, delaying the admission of elective patients means that a hospital requires fewer beds than if a decision is made that all patients (elective and emergency) should be admitted on the day that their needs for care are identified.

Chains cross unit boundaries and represent the total range of resources required to produce a product or to treat a patient. Hence, a chain might be regarded as a patient pathway: for example, the chain of care for stroke might consume resources provided by imaging departments, general and stroke specific hospital wards, and physiotherapy departments. Chain logistics is concerned with coordinating the appropriate and efficient allocation of resources along patient pathways or product lines, for example, scheduling patient flows in order to avoid delays or ‘bottlenecks’ in patient care.

Unit logistics is discussed in greater detail in chapter 4: in the planning framework this is referred to as ‘resources planning and control’. The discussion of the allocation of resources within units considers issues such as: whether or not resources can be ‘shared’ by more than one patient group; whether resource use in one unit ‘leads to’ or ‘follows’ resource use in another unit; and whether or not a resource is scarce and as a result might represent a ‘bottleneck’ in the delivery of services. For example, CT scanning facilities can be used by more than one patient group and represents, therefore, ...