- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Women in Islam investigates the ongoing debate across the Muslim world and the West on the position of women in Islam.

Anne-Sofie Roald focuses on how Islamic perceptions of women and gender change in Western Muslim communities. She shows how Islamic attitudes towards social concerns such as gender relations, female circumcision, and female dress emerge as responsive to culture and context, rather than rigid and inflexible.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women in Islam by Anne-Sofie Roald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Islamic Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theoretical and methodological reflections

Introduction

Interpretations of social issues in the Islamic sources have always been affected by interaction with surrounding social structures. However, there has in the past been little awareness that this is the case, and as a result Islamic social life has been presented as an absolute divine system. The recent recognition among Muslims of alternative possibilities with regard to the structuring of society, even within the framework of Islam, can be attributed to the fact that the last half of the twentieth century has been an era of widespread migration. In Part I, I identify changes in attitude which might be anticipated as a result of the Muslim experience of migration, asking how Muslims have been perceived by non-Muslims and how Muslims perceive themselves. This leads me to reflect on a number of theoretical and methodological issues relating to the question of continuity and change in Muslim communities in Europe. In Part II I present empirical material which demonstrates the extent to which such changes have in fact taken place among Muslims.

In research into Islam, misunderstandings and misconceptions arise both from the side of researchers and from the side of those being researched. This leads me to explore the reasons why Muslims agree to be objects of research, and to ask if researchers sufficiently understand these reasons. What happens when the researchers are themselves Muslims? Does this influence their research findings? These questions are addressed in Chapter 1.

The Islamic presence in Europe is perceived as a homogenous mass. However, even within national groups there are wide variations in terms of class, education and ideological standpoints. Arabic-speaking Muslims are influenced by many organisations active in Europe and based in the Arab world, and their different approaches to the Islamic message mean that Muslims sometimes come to divergent answers in response to the same questions. In Chapter 2 I address some of the research implications of this.

Any research project such as this must define its boundaries, since the potential area of research is too vast to encompass within one study. This means recognising the partiality and limitations of the research, while identifying those groups and perspectives which are most significant in terms of the questions being asked. In Chapter 3 I explain the process of selection and I say why I chose to focus on particular groups and movements in the course of my research.

Chapter 4 discusses ways in which widespread migration initiates processes of change in Muslims’ understanding of the Islamic message, with the introduction of new cultural paradigms challenging traditional solutions to problems. Patriarchal values and social structures, which are a common feature in many Arabic-speaking countries, have affected Islamic interpretations and legislation in social issues. In their encounter with European society with its notion of equality between the sexes, Muslims tend to be influenced by the views of the dominant culture in their reinterpretation of social issues in the Islamic source material. Such changes are hard to evaluate in a scientific study so I have chosen a bipolar model, with two cultural patterns on either end of a scale, in order to illustrate how they might take place in the Muslim diaspora.

1 Research on Muslims

Introduction

I begin this study with a discussion of how Islam and Muslims are perceived in a western context and how Muslims’ search for identity in a new cultural context tends to create misconceptions between various groups in society. During the course of this study I have been asked why I have chosen to study Arab Islamists and not, for instance, Bosnians (who are the original European Muslims), South Asians or Turks. I have even been confronted by one researcher who compared my study of well-educated Arab Islamists to a study of groups of illiterate Turkish women in European suburbs. These questions point to the huge problem researchers on Muslims and Islam face in a European context which brings together diverse Muslim groups from different classes with different cultural, educational, ethnic and national backgrounds. On the one hand, the problem of the distinction, or rather the ‘non-distinction’, between various kinds of Muslims is a result of the widespread model of thinking in terms of ‘us and them’ such that unacceptable characteristics are projected onto ‘them’. On the other hand, Muslims themselves also contribute to the confusion. As Islam is the feature which apparently distinguishes Muslims from non-Muslims, many who in their home countries would not identify themselves in terms of Islam, will regard themselves first and foremost as Muslims in the cultural encounter with ‘the West’.

Muslims in contemporary research

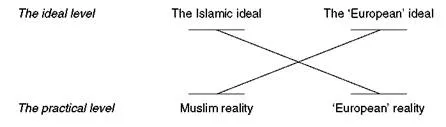

I want to draw attention to how Islam and Muslims have often been perceived in the public arena, or more specifically in official debate, as well as in the academic world in non-Muslim societies. In a multi-cultural context there tends to be dissonance between the ways in which various cultural groups perceive each other. This might be true for whole societies as well. Psychologically speaking, a person would judge her/himself by her/his ideals whereas one tends to judge others by their practices, and this is also true of interaction between different cultural groups (Elias and Scotson 1994). Muslims living in Britain, for instance, would judge the majority group, the British, as a homogeneous group, referring to it as ‘the other’, thus emphasising characteristics and behaviour which are most apparently different from their own. Moreover, they will judge, not in view of their own praxis, but in view of their Islamic ideal. The same is true for the British, who will judge the apparent characteristics of Muslims in view of their own ideal based upon a conception of what is typically British. As interaction between Muslims and the majority population in most of the western European countries seems to be limited, the apparent, i.e. the outstanding, characteristics of the other cultural group become those which are highlighted in comparison with one’s own ideological stance. Apart from judging one’s own group according to an ideal standard and judging outsider groups according to their actual practice or behaviour, individuals belonging both to the majority and the minority group tend to ‘stereotype themselves as well as others in terms of their common attributes as group members’ (Turner and Giles 1981: 39). Moreover, I have observed that there is a tendency on both sides to perceive the other group in terms of that which is regarded as most ‘extreme’ in relation to one’s own stance or practice.

Kenneth Ritzén, a Swedish historian of religions, in his numerous lectures1 on the relationship between Muslims and majority societies uses the following model to illustrate the relationship:

Figure 1

With regard to the majority society, those who have contact with Muslim immigrants and transmit their impressions to the rest of society are often social workers, teachers, etc. and they might focus on particularities of the group, such as identifying only problematic cases, rather than offering generalised descriptions. Moreover, the media has the potential to function as a mediator between various social groups but it is to a very large extent governed by the economic demands of promoting news, and news tends to be that which diverges from social norms. For instance, in Norway the Rushdie case had a powerful impact upon the ways in which the majority society perceived the Muslim minority. This was due to the fact that some Muslims of Pakistani origin who openly professed their support for the death sentence2 were quoted in almost all newspapers and on radio and television programmes due to an assassination attempt on Rushdie’s Norwegian publisher. Many Muslims in Norway publicly rejected the validity of the death sentence but they were not usually quoted in the media. The result was that Norwegians formed the impression that Muslims living in Norway supported the death sentence. The consequence of such mutual misconceptions, which arise as a result of the two levels of comparison described above, is increasing inter-group hostility.

In the academic sphere, similar dissonances in the perceptions of various cultural groups can be observed. According to two researchers, Fatme Göçek and Shiva Balaghi, studies of the Third World ‘often contain Orientalist elements that treat social processes in cultures and societies other than [their own] as static or, at best, derivative’ (Göçek and Balaghi 1994: 5). They claim that these studies tend to emphasise tradition in a way that establishes the idea of the tradition’s immutability, since ‘in order to justify its own hegemony, the western gaze needed to portray tradition in the Middle East as an immutable force’ (Göçek and Balaghi 1994: 5). The Swedish researcher, Aleksandra Ålund, also points out how in the official debate in Sweden, ‘the immigrant culture’ is looked upon in terms of ‘traditionalisms’ in contrast to ‘the detraditionalised Swedish culture’ (Ålund 1991: 19). She further claims that in this picture ‘stereotyped generalisations’ about immigrant youths or immigrant women have made them become ‘cases’, and thus they have been exposed to ‘negative fame’, to use Michel Foucault’s terminology (Ålund 1991: 19).

Edward Said’s criticism of the occidental way of depicting Islam and Muslims has been regarded as polemic or provocative, but his arguments have created repercussions in the academic world. Said, in his book Orientalism (1979), calls attention to the close link between knowledge and power in the relationship between ‘the West’ and ‘the Orient’ (Said 1979).3 Although as a scholar of contemporary literature Said has taken his material mostly from the literary sphere, one can read his analysis in political terms. He shows that knowledge is power since ‘the Orient’ could be ruled by ‘the West’ because ‘the West’ came to know ‘the Orient’. However, at the same time Said also points out that the particular knowledge which ‘the West’ came to obtain about ‘the Orient’ was not always the same knowledge as ‘the Orient’ had about itself. A parallel argument which might also be interpreted in terms of this insider/outsider perspective is that of the French anthropologist, Louis Dumont, who suggests that social scientists tend to project their own prejudices onto the phenomena they are studying (Dumont 1977).4

In a later work, Covering Islam (1981), Said further discusses how Islam has been represented in western academia and in society at large. He points to the struggle which has gone on for centuries between Islam and ‘the West’, and he sees a connection between the contemporary stereotyping of Islam in western countries and the Middle East’s oil supplies. He observes that there are huge generalisations on both sides, but the distinction between them lies in how the two entities have been presented. He writes:

At present, ‘Islam’ and ‘the West’ have taken on a powerful new urgency everywhere. And we must note immediately that it is always the West, and not Christianity, that seems pitted against Islam. Why? Because the assumption is that whereas ‘the West’ is greater than and has surpassed the stage of Christianity, its principal religion, the world of Islam – its varied societies, histories, and languages notwithstanding – is still mired in religion, primitivity, and backwardness. Therefore, the West is modern, greater than the sum of its parts, full of enriching contradictions and yet always ‘Western’ in its cultural identity; the world of Islam, on the other hand, is no more than ‘Islam’, reducible to a small number of unchanging characteristics despite the appearance of contradictions and experiences of variety that seem on the surface to be as plentiful as those of the West.

(Said 1981: 9–10)

It is interesting to note how Said uses the word ‘Islam’ in a geographical sense, which leads me to suggest that the opposition between ‘Islam’ and ‘the West’ might be perceived as a geographical opposition by a nonMuslim Palestinian such as Said. Since media stereotyping tends to equate Arabs with Islam, for example, or in many cases the Third World with Islam, a non-Muslim coming from a Muslim ‘cultural sphere’ might perceive such an opposition in geographical rather than in ideological terms.

Said further claims that ‘the term “Islam” as it is used today seems to mean one simple thing but in fact is part fiction, part ideological label, part minimal designation of a religion called Islam’ (Said 1981: x). He observes that ‘there is a consensus on “Islam” as a kind of scapegoat for everything we do not happen to like about the world’s new political, social, and economic patterns’ (Said 1981: xv).

Said’s discussion of the tension between ‘the West’ and ‘Islam’ is I believe grounded in the common debate in society in which the media is the main actor. When it comes to academic research on Islam and Muslims his analysis is not always applicable (cf. Rodinson 1991; Kepel 1985). What is apparent, though, is that there is a view of Islam in western countries which is different from the view of Islam that Muslims have. On the other hand, it is important to remember, as Said has rightly pointed out, that Muslims likewise tend to have distorted pictures of ‘the West’. There is therefore a pattern of mutual misconceptions, and it is interesting to note how this pattern is very much a factor in the interaction between ‘Islam’ and ‘the West’, particularly on a general level.

In the academic sphere, I would argue that despite much excellent research, there are still researchers who, when dealing with Muslims or Islamists, tend to treat them as a homogeneous group (cf. Kepel 1993; Zubaida 1989; Moghadam 1990). Although many researchers agree that Muslims in different countries follow various patterns of behaviour, this comprehension of Muslim heterogeneity has not always been extended to include the variety of Muslim immigrant communities in western European countries. For example, there has been great interest in the study of Muslim immigrant women but many of these studies - from undergraduate to postdoctoral level - represent Muslim women as a single entity (cf. Moghadam 1990).5 Although efforts have been made to distinguish between Muslims of different nationalities, less importance has been attached to class and cultural backgrounds within one and the same national group. Furthermore, there has been insufficient awareness of the Muslim woman’s relation to Islam. For a Muslim woman to emphasise her identity as a Muslim does not necessarily have to do with religious stances or religious feelings. Separation from their native countries and feeling that they are aliens in a foreign culture might push many Muslims to define themselves first and foremost as Muslims, whereas in different surroundings they would operate with other self-definitions. In such a situation ‘Islam’ tends to become a term of contrast which a Muslim woman might use to designate a traditional structure, history and society. Religious and ethnic identity cannot be isolated from other social influences. Claims to ethnicity, religiosity and gender might become means of expressing frustrations with prevailing cultural norms, which are then conceptualised by researchers who formulate theories and create social concepts.

Solh and Mabro have observed that some studies tend to be theologo-centred (El-Solh and Mabro 1994: 1), so that researchers interpret phenomena mainly from a religious point of view (cf. Huntington 1996; Pryce-Jones 1992; Sivan 1992). Other researchers take the opposite stance by omitting religion as an instrument of analysis in modern societies (cf. Mutalib 1990; Muzaffar 1987; Nagata 1984). I have observed that in the former approach, for example, researchers tend to talk in terms of Islamic politics when analysing the politics of Muslim states which often follow a secular political scheme (cf. Huntington 1996; Sivan 1992). With regard to the latter approach, my observations suggest that there is a one-dimensional horizontal analysis with no regard to the religious sphere, which in reality has a firm grasp on a great part of the world’s population. Many Muslims view worldly and religious concerns as closely interwoven, yet researchers could miss the religious dimension which is important to take into account in the analysis of Muslim societies. This applies particularly to researchers who come from those parts of the world where the mainstream ideology demands a separation of church and state. An example of such horizontal analysis concerns discussion about Muslim women’s veiling which has tended to be reduced to a socio-political phenomenon, since researchers do not consider the religious significance of the headscarf/veil (khimār). However, although I am critical of studies which leave out some of these ‘realities’, I am also aware that all studies have to be selective. Given that the various fields of science have different methods and fields of interest, it is difficult for any one researcher to grasp the whole picture. Thus one must opt for a variable study which identifies one variable and presupposes other variables as constants.

The aim of this present study is in contrast to the two approaches to research outlined above, since I approach Islamic ideas as they are perceived by Islamists. I offer an ‘insider’s’ perspective primarily due to my own relationship to Islam, but also because I give Islamists the opportunity to speak for themselves, thus presenting an ‘inside’ rationale for Islamist ideas and practices.

The political aspect of Islam

Many researchers on the recent Islamic resurgence concentrate on the political side of Islam while neglecting other aspects, which may be a consequence of the Islamist emphasis on political matters. With the nineteenth century’s salafīya movement under the leadership of the an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: Theoretical and methodological reflections

- Part II: Reflections on the empirical material

- Notes

- List of scholars

- Glossary

- Bibliography