Chapter 1

Metasynthesis of the neurobiology of Alzheimer’s disease

Thomas Arendt

Dementia is a major public health problem

Dementia affects both genders and all socio-economic and ethnic groups. Dementia is not a disorder in its own right; it is rather a complex syndrome of brain dysfunction with a number of potentially different underlying causes. Dementia can be defined in the following way (WHO 1986):

Dementia is the global impairment of higher cortical functions, including memory, the capacity to solve the problems of day-to-day living, the performance of learning perceptuo-motor skills, the correct use of social skills and control of emotional reactions, in the absence of gross ‘clouding of consciousness’. The condition is often irreversible and progressive.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is by far the most common cause of dementia. It appears to have several causes, some of which are very rare. These are discussed later in the chapter. AD accounts for about one-third of all dementia cases in the elderly. Another third is of vascular origin (resulting primarily from the accumulation of strokes or infarcts), and the last third are mostly mixed cases of both AD and vascular dementia. Dementia, and in particular AD, occurs primarily in elderly persons (Arendt 2001; Terry et al. 1999).

Aging in itself, however, is a physiological process, and AD is not an inevitable consequence of age. (AD can also occur in persons in their fourth and fifth decades, though this is uncommon.) In the absence of dementia, cognitive performance can remain relatively stable with age. This apparently stable performance does not exclude the possibility of some age-related cognitive deterioration, because learning can potentially counteract against small declines. During a lifetime, an individual can accumulate a number of small (though possibly deleterious) impacts. Each impact, in and of itself, might be insufficient to cause functional impairment, however when they accumulate progressively they could reduce the reserve capacity of the brain. In this sense, aging influences the onset and course of a number of disorders, and it is the most important risk factor for dementia.

The incidence (i.e. the number of newly diagnosed cases) of dementia rises drastically with age, and its prevalence doubles every five years. At the age of 65, about 1 per cent of the population has a dementing illness of some sort. Thereafter, the prevalence (i.e. the percentage of people that is affected by a disease) has been estimated to increase up to 30 per cent (some say 50 per cent depending on which criteria for diagnosing dementia are used), for persons aged over 85. AD is the most common form of dementia in the Western industrial countries and affects about four million people in Europe and a similar number in the USA. The continuing growth of the elderly population is leading to an ever-increasing number of dementia patients worldwide. Within the next 20 to 30 years, the number of people aged over 60 years will double and the number of persons with dementia will rise accordingly. While so far age-related disorders have been a major health problem only in the Western world, the less developed countries will catch up with these figures within the next 50 to 60 years.

AD is a chronic progressive disorder

In the absence of dementia or other diseases, older adults may expect relatively stable cognitive function and few difficulties with everyday performance of accustomed activities, a process referred to as ‘successful aging’. A decline that is considered to be age related may thus reflect the effect of unrecognized very mild dementia. Some persons requesting a diagnosis have cognitive complaints of uncertain significance and may only demonstrate questionable deficits on quantitative testing. It may thus be difficult to classify such persons as either ‘normal’ or ‘having dementia’. Hence, the term mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has been coined. For many persons with MCI, this may indeed represent the initial presentation of AD. It has been estimated that about 25 per cent to 40 per cent of these progress on to having officially diagnosable dementia within two and three years, respectively.

Dementia usually starts with relatively slight impairments and progresses to a point where all skills of communication and self-care are lost. The rate of progression depends on both internal and external factors. With the help of a scale such as the dementia rating scale, one can place a patient into one of five stages along a continuum from healthy to severely demented (Table 1.1).

The development of the NINCDS/ADRDA criteria have made a more standardized clinical diagnosis of AD possible. These criteria establish three levels of diagnostic certainty. Probable AD is present when dementia is characterized by gradual onset and progression, when deficits are present in two or more cognitive areas, and when other disorders that could cause dementia are absent. Possible AD is present when the patient has variations in the presentation of dementia (e.g. disproportionate language dysfunction early in the course). Definite AD can only be diagnosed when the clinical diagnosis is histopathologically confirmed by biopsy or autopsy. The clinical diagnosis of ‘probable AD’ has an accuracy of 90 per cent or greater, if made by a memory clinic or specialist multidisciplinary diagnostic team.

Table 1.1 Functional levels of AD and corresponding developmental ages during childhood according to Reisberg

The histopathology of Alzheimer’s disease

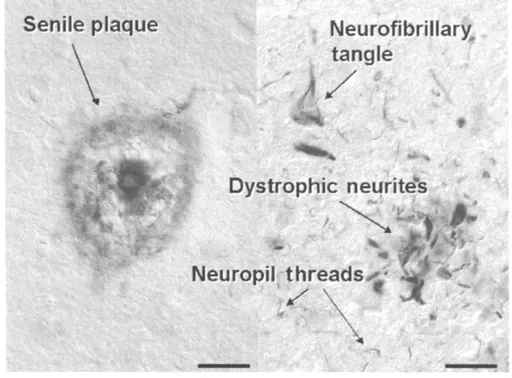

The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease is mainly based on the exclusion of other possible causes of dementia and disorientation. This careful exclusion process is particularly important for the identification of those forms of illness which are treatable and, therefore, at least partially reversible. Remember that a 100 per cent certain diagnosis can only be established after postmortem examination, which confirms the clinical diagnosis in most cases. The appearance of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the cerebral cortex is the typical pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Both plaques and tangles are cause by protein deposits, but by two different ones. In the case of a plaque, the protein (beta-amyloid), accumulates outside of the nerve cell. In the case of tangles, the protein, called tau, accumulates within nerve cells (also called neurons or neurites).

Figure 1.1 Senile plaques, consisting of aggregated amyloid ß-peptide (left) and neurofibrillary tangle, dystrophic neurites and neuropil threads, consisting of paired helical filaments made up by the cytoskeletal protein tau (right). Scale bars, left: 50ìm, right: 20ìm.

On the basis of their presence the post-mortem diagnosis of AD is established (Figure 1.1). The occurrence of both senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, however, is not absolutely specific for Alzheimer’s disease. They are also found in other dementing disorders such as elderly with Down’s syndrome, posttraumatic dementia (boxing dementia) and to some very small extent are sometimes found even in normal elderly who show no mental impairment.

Plaques

Plaques, also referred to as ‘senile plaques’, are extracellular (outside of the cell) deposits of a small peptide (a chain of organic compounds called amino acids which are required for the production of proteins) called ‘amyloid-ß-peptide’, that have become intermingled with ‘glial cells’ (a type of brain cell which is part of the immune system) and ‘processes’ of neurons (called axons and dendrites, which are the equivalent of arms and legs on a human, which bring the cell into electrochemical contact with other cells) which have been damaged. The amyloid-ß-peptide is formed by the ‘proteolytic processing’ (made from the breakdown of other proteins) of a larger cell surface protein (called amyloid precursor protein, APP). Beta amyloid progressively accumulates into plaques and into the walls of blood vessels. Plaques are thus rather compact spherical structures with diameters of up to 200ìm (200 millionths of a meter) that eventually occupy a considerable portion of the brain tissue. The mechanismsleading to the generation and deposition of the amyloid-ß-peptide (and thus to the formation of plaques), are still not understood very well.

A number of enzymes (a protein which speeds up biochemical reactions) have been identified that control the formation of the amyloid-ß-peptide from its precursor protein. These enzymes have been called ‘secretases’ since they regulate the ‘secretion’ of the peptide. Secretases are one target for a number of potential therapeutic approaches currently under way. These strategies aim to reduce the generation of amyloid-ß-peptide and thus the formation of senile plaques. It remains questionable, however, whether reducing the levels of amyloid-ß-peptide will be of any benefit, since its production appears to be a consequence, rather than a cause, of cell death. Accumulation of amyloid-ßpeptide in the brains of AD patients is most likely the result of impaired clearance of amyloid-ß-peptide through the vascular system. Under normal conditions, in the non-diseased human brain, amyloid-ß-peptide is produced at very low amounts and cleared through the vascular system. If it is produced at a much higher rate, as in AD, its clearance through the blood is insufficient and it seems to passively accumulate into plaques.

Neurofibrillary tangles

Neurofibrillary tangles (see Figure 1.1) are localized within the cell bodies of neurons. They consist of twisted filaments (called paired helical filaments), which are formed from a small cytoskeletal protein called ‘tau’. The normal function of the tau protein is to stabilize the cell’s ‘microtubules’. (Microtubules are pipe-like protein structures in the cell’s axonal process. In additional to providing structural support for a cell, they also provide a sort of ‘rail track’ for the transport of many nutrients and substances within the cell.) In AD, the binding of the tau protein to the microtubules is altered, resulting in twisted pairs of tau which destroy the shape of the microtubules, reducing their ability to transport substances normally.

The binding of tau protein to microtubules is regulated by a process known as ‘protein phosphorylation’ (i.e. the binding of phospho-residues to the tau protein). If protein phosphorylation is high, i.e. a lot of phospho-residues are bound to the tau protein, its interaction with microtubules is made unstable, or ‘labilized’. As a consequence, the ‘rail track’ structure of the microtubules breaks down and the ‘axonal transport’ fails.

For reasons that are unknown, the phosphorylation of the tau protein is elevated in AD. The microtubule structure is disturbed, and the tau protein, which does not bind efficiently to the microtubules, accumulates in the cell body (the main part of the nerve cell, not its processes) of the affected neuron in the form of ‘paired helical filaments’, which are the major component of neurofibrillary tangles. These twisted filaments (paired helical filaments) also occur in degenerating neurites (dystrophic neurites) and in the neuropil (neuropil threads) (see Figure 1.1).

Similar ‘intraneuronal (inside the cell) inclusions’ of the tau protein also occur in other neurodegenerative disorders that share clinical features with AD and are commonly referred to as ‘tauopathies’. These include Down’s syndrome, progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, Pick’s disease, and frontotemporal dementia with Parkinson’s linked to chromosome 17.

It is important to note that, during the stage of ‘neuronal fibre outgrowth’ in brain development, this tau protein is highly phosphorylated, and also destabilizes the structure of microtubules. This developmental destabilization of the microtubule structure is exactly the same as what happens in AD. However, during the developmental stage, it is a necessary prerequisite for the axon to be able to grow, and does not lead to harmful, deleterious effects.

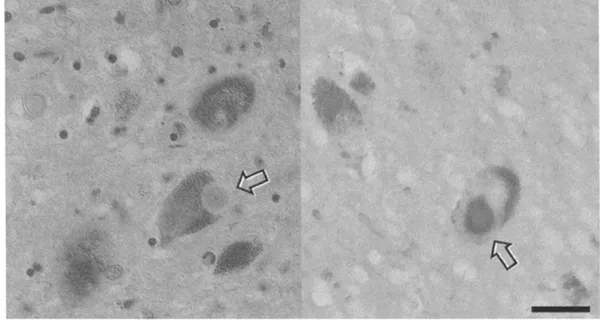

Parkinson’s disease

The second most frequent neurodegenerative disorder after AD is Parkinson’s disease (PD). PD clinically involves extra-pyramidal (nerve cell groupings associated with involuntary control of muscle activity) motor system abnormalities and is characterized (pathologically) by the presence of Lewy bodies. Lewy bodies are intracellular spherical inclusions of a synaptic protein called ‘alpha-synuclein’. It is not known what their presence does to the cell, or what causes their formation. Lewy bodies are found within neurons of the part of the brain called the ‘substantia nigra’ (Figure 1.2). Other than PD, Lewy bodies have also been associated with AD, where they are found in cortical neurons. This suggests an important interaction and common mechanism in the pathogenesis of the two diseases. About 25 per cent of patients with PD also develop dementia. Conversely, about 30 per cent of patients with AD develop extrapyramidal motor disturbances. An association between cortical Lewy bodies and dementia has recently started to be increasingly recognized, and ‘Dementia with Lewy bodies’ is now regarded as an independent dementing disorder that can be distinguished from AD on the basis of particular visual hallucinations and extrapyramidal signs.

Which neurons degenerate in AD?

While plaques are more uniformly distributed throughout the cortex, neurofibrillary tangles show a typical sequence of formation throughout different parts of the cortex (Figure 1.3). The number of neurofibrillary tangles, moreover, correlates with the degree of mental impairment while such a correlation is not observed for senile plaques. The formation of neuroflbrillary tangles within a neuron apparently critically impairs its viability and after years or even decades might eventually result in cell death. This process is called neurofibrillary degeneration. The development of neurofibrillary tangles first starts in the transentorhinal and entorhinal cortex.

Figure 1.2 Lewy bodies (arrows) in the substantia nigra of incidental Lewy body disease (left: hematoxilin-eosin staining; right: immunostaining for alpha-synuclein). Scale bar:

20ìm.

...