- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching Communication

About this book

We learn most of our communication skills without consciously working at them. Teaching Communication sets out what those skills are and how to develop them.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter one

What about communication?

This book is small but ambitious. It will deal with communication (including media) teaching in a wide range of situations, as taught by a diversity of teachers. We believe that we can take this approach precisely because communication work in all areas does have a great deal in common, whatever the syllabus or terms of reference. Indeed, one of the purposes of this book is to make this common ground apparent, to bring us all together.

Our audience

You may be working with students of very different abilities and interests, in a wide range of institutions, or preparing to teach for the first time, but we hope that we have something to say about how communication may be taught which will be useful to all of you. This means that we are addressing those whose main interest is media studies, as well as those in communication work. It means that we are saying something to school teachers dealing with TVE or CPVE, and for FE teachers working with BTEC courses or other pre-vocational work. We address ourselves to GCE and GCSE teachers alike. And we hope that colleagues in polytechnics will also find something of value here. Certainly we hope that those being trained as teachers will want to read this book, and that we can introduce them to new concepts, new approaches, and a new subject.

In fact communication (or communication studies) is not so new any more. The first A-level examination was held in 1978, and degrees in the subject have been running for well over a decade. Communication work in a pre-vocational context at all levels has expanded enormously in the 1980s, with new syllabuses and forms of assessment significantly affected by the creation of BTEC. All the communication syllabuses and parts of courses have been modified and rationalized in content and objectives. This rationalization has brought those involved in pre-vocational and the so-called academic communication work closer together in many respects. We do not subscribe to value judgements about the relative merit of, say, A-level Communication Studies and BTEC People in Organizations. It is a fact that pre-vocational courses do not require as much explicit knowledge and use of theory as their GCE and GCSE counterparts. But there is still much common ground, not least in terms of those basic principles which underlie any communication practice. The BTEC National skills statement represents a set of objectives that A-level teachers could do well to take on board. Prevocational communication is not utilitarian per se; practical work is a worthy part of any communication course.

Our purpose

The main purpose of this book is to talk about what we teach and how we teach it. We will offer straight ideas about topics, concepts, and teaching methods. To this extent, this book takes a practical approach. We cannot please everyone, but we hope that every reader finds some ideas, and even some teaching methods or approaches, which they can take away and use. You will therefore gather that this book may do a little bit of preaching and flag-waving, but on the whole it will mark out territory and suggest possible routes across it. With the exception of some remarks in this chapter, we are not really interested in arguing the case for communication as a subject. If you are reading this book, then you are likely to be a practising communication teacher, or you think you will be one, or you are just curious. Whichever you are, we think it best to talk about the teaching. So this is not a book which espouses any particular educational theory. Nor will you find that this opening chapter is in any sense built on references to such theory or to the luminaries of that theoretical world.

The philosophy behind this book and communication work

On the other hand, we are very prepared to offer some kind of philosophy on communication teaching as we see it. This isn’t a justification, it is simply an account of the way we see things. These ideas are woven into this book. You may find them useful to argue through if you need to build or rebuild a communication course.

To begin with, we take the view that one is dealing with a process, in the case of any example of communication. As a process, communication is something continuous and active, with no boundaries and no beginning or end. As communicators we are everything that we have been and that our culture has been. But this does not mean that all is chaos. What we do is to examine parts of the process, and see how they fit together. One looks at different theories for describing that process. And still one can deal in some principles—that communication will always have a purpose and a context, for example, and that such factors will always affect how communication takes place. So there are basics to deal with and to build on.

We also prefer to integrate the semiotic approach to communication with that of process. Communication is indeed all about the construction and use of signs and meaning, from one point of view. It is perfectly possible to see signification as working within process. Indeed, signs are the visible part of process. Unless one is able to make signs, to encode and decode them, then one lives in a mean-ingless world, unable to build bridges with others.

We accept that our communication techniques and sharing of meanings are rooted in often unacknowledged social, cultural, economic and political experiences and traditions. We all create our own meanings for and interpretations of communication acts in order to understand ourselves and the societies in which we live. Our readings of messages reflect our cultural and personal beliefs, biases and expectations. No two people will make an identical interpretation of the same text. They may make interpretations similar enough for them to agree about its meaning in general, or at least to agree as to why their interpretations differ. Since we are surrounded by messages from the various mass media it is essential that educational experience should enable people to analyse these messages and to understand how they are created. An understanding of the general processes of communication provides a way to probe the nature of media messages. At the heart of the study of communication is an attempt to understand and to make use of the processes and methods by which people use culturally-based signs and codes to express themselves and to share meanings with other people.

Another point which we would take as basic is that all study of communication is concerned with how and why communication takes place. We may study it for interest and pleasure; we may wish to understand it so that we can become better communicators. But it is still fundamental to be able to explain why we communicate as and when we do. It is also crucial to understand how we carry on this process if we are to understand other people and be understood by them.

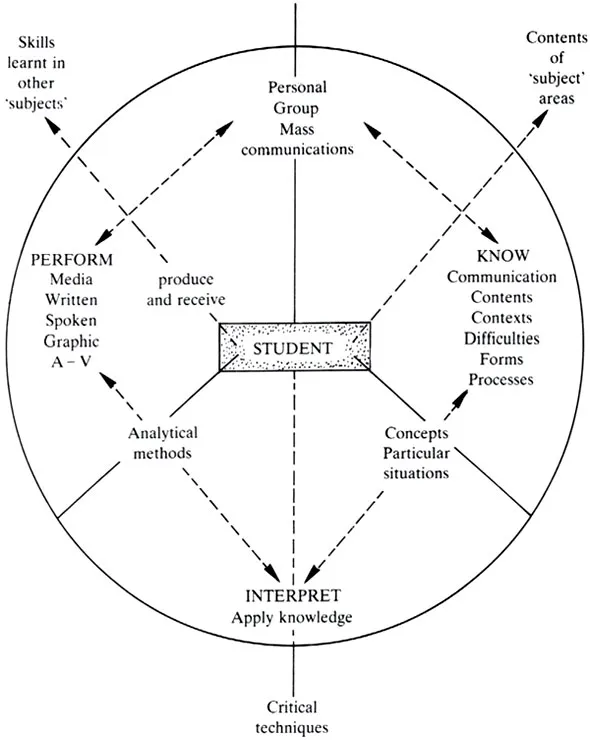

We would also take the view that all communication courses can, in varying proportions, be described as being about description, interpretation and practice. That is to say, we must be able to describe accurately what is happening when communication takes place. We must then make sense of what we know. Finally, we must take something of our learning and put it into practice to become effective communicators.

This notion of becoming an effective communicator should also be implicit in even ‘academic’ courses. What is the use of knowledge and understanding if we can do nothing with it? And we do believe that it is possible to talk about effective communication, without invoking a rationale which is solely functional and instrumental. Being an effective communicator is obviously about communicating clearly what we mean, and being understood by others as a conse-quence. But it is also about personal qualities, such as consideration for others. An effective communicator takes into account as many factors in a given situation as possible. Being effective is not just about getting your own way, or delivering so many customers per minute to an advertising client. It is also about elements such as compassion and sympathy. An effective communicator will have the skill of empathy and will use it.

Another assumption which underlies our approach and which may underpin any communication course is that one is teaching concepts which relate to skills. These concepts are summarized in terms, factors, and models. They identify elements in the communication process, and help describe how communication is used and how it is carried on. They help both description and interpretation. From one point of view, when constructing a course, one must sort out what concepts are to be taught, explicitly or implicitly. But ideas are no good unless they inform practice.

In some quarters the notion of communication skills has become a dirty word because it has been misused, most frequently as a way of glossing over the fact that one may feel one is teaching something rather basic and very functional in a course which is in truth only generating job fodder. But in a more proper sense there is nothing wrong with teaching functional as opposed to intellectual or social skills.

If functional communication skills are approached as unproblematic, self-evident, mechanistic tricks which will make one a ‘good’ communicator, then this denies the subtle problem-solving choices that any communication task presents. Even in the simplest act of communication there are many choices to be made about what, why, when and how. For example, a model letter for a job application represents only a selection of topics and approaches: the writer of an actual letter must also make particular choices about vocabulary, information, structure, layout, tone and style, all of which reflect their personality, their view of who will read it and of the desired effect on this person. Functional skills presuppose a context of intellectual and social skills, of knowledge and understanding. A communication course should deal with all three types of skill—all are valuable in terms of personal as well as vocational development.

This also leads on to the point that, even in overtly vocational communication courses or programmes, an effective course will still develop the person and their capacity to handle relationships, as well as their ability to take effective action. We take it as basic that a communication course should, in various degrees, be concerned with these three kinds of development.

In talking about functional and social skills or relationships and action in the same breath, we run the risk of being accused of trying to reduce what is complex and personal to a set of simplistic rules and doubtful nostrums for social success. At the same time, it is true that one can identify agreed skills, and identify some conventions of behaviour that are likely to contribute to successful outcomes of interaction in personal and social terms. Not only do we think that it is reasonable to deal in various communication skills, but also we think that knowledge and awareness brings the power to control. So the argument for teaching an understanding of what is happening when we communicate is that it gives those with that understanding the ability to use it to modify their communication behaviour. This does not mean that one has to use theory or abstract terms. One does not have to get deep into semiology to convey the idea that many communication problems stem from the fact that the relationship between signs and meanings is arbitrary and culturally conditioned.

We are also writing out of a belief that communication cannot be neutral per se—that all utterances have behind them a weight of cultural attitudes and values. Part of the point of at least some communication courses is to identify and articulate these assumptions, and to try to evaluate the relative degrees of selection and bias which have formed them.

Finally, we consider it a basic principle that, begging a few minor qualifications, communicative competence is learned and not inherited. It is our philosophy that learning about communication is learning about what we have learned, and how we have learned it. Again, this knowledge gives us the potential for re-learning how we communicate. People always have the capacity for change. But that capacity may not be used unless the individual sees a way of changing and a reason for changing. Learning of any kind puts power in the mind of the learner. Communication practical work encourages use of that power to benefit the individual as a person, as a social being, and as a maker of communication in all its various forms.

Figure 1.1 Student-centred learning of communication

Some special features of communication work

Having dealt with the assumptions and philosophy underpinning our approach to communication work, we would now like to turn to our ideas about what is distinctive in communication study and practice. We are not claiming that all topics, concepts, or teaching approaches to communication are unique in themselves (though some are). But we do think that when you put these together, you have something different, valuable and interesting.

First, there is the holistic approach—that is to say, communication teachers are dealing in a body of theory which pulls together and deals with both face-to-face communication, and mass communication. Acts of and experiences of communication figure largely in our lives, so we think that it is distinctive and useful that there is such an approach which attempts to make coherent sense of these acts and experiences.

Then there is the question of the range of media dealt with, both in theory and in practical work. This is particularly relevant when one discusses the relationship of communication to English or to media studies. Clearly, the three (call them subjects if you like) do co-relate. But equally obvious is the fact that only the broad communication approach accommodates all media or languages. It is significant that English in particular has been the subject from which many communication teachers have come, and that it is the subject which has recently tried to accommodate media elements in particular within, for example, GCSE syllabuses. However, communication teaching has already become established as a separate discipline, so one must accept these subjects as being complementary, and not try to duplicate work which communication courses are already covering.

Another point which seems distinctive to communication work is the integration of theory and practice. One should inform the other; indeed, one can teach out of one or the other. One may draw conclusions about communication factors and principles from an activity which has been carried out, or one may explain concepts and then both reinforce them and make them ‘real’ through the experience of some activity.

Communication work is also distinctive in the support which it can offer to other subjects in the curriculum. Indeed, it may be unique in its central role within any curriculum. Some people even feel that there should not be such a separate subject or module on the timetable, but that all communication work should be taught in the context of other subjects. However, we think that this would not only ignore what is distinctive about communication theory, but also that it would undermine the effective application of communication to other work. For example, it makes more sense to teach visual analysis, signification and meaning at one time, and then apply them to art, media, and geography, rather than duplicate effort. More importantly, it is unlikely that geography teachers would ever take such an approach, perhaps commenting on ways in which geography enshrines cultural attitudes and values in the apparently neutral pictures which are used to illustrate some textbooks.

Chapter two

What does one teach?

This is of course the question facing anyone in communication teaching at the beginning of a course. The existence of a syllabus is some help, but no real answer. It gives one terms of reference, but it isn’t a course plan. Experience certainly helps, but it doesn’t necessarily make the answer any easier. In fact it sometimes makes things more difficult because one has accumulated more material which one wants to use.

It is also a truism that content and method play off one another, so we are already having some problems in designing this chapter to deal with what one teaches, and leaving how one teaches until the next chapter! But that is also an inherent problem in teaching any communication course. What one gets across is as important as how one gets it across. So we are going to regard these two chapters as two ways of getting to the same place.

In a sense we are also putting our heads in the lion’s den by incorporating BTEC National because it is largely supposed to be led on a skill basis, to be all about practice and method. However, first it is true that skills are present in any communication course, and are as much a part of context as anything else. Second, we shall demonstrate that the notion of skills extends beyond functional competence. Third, activities must in fact be concerned with ideas and principles—of communication in our case. And fourth, when for example one is dealing in negotiating skills or team/group skills, one is often drawn back into explaining the ideas which describe effective communication, and which help the student interpret what is going on. The same argument is true for GCSE, notwithstanding its practical inflexion. In other words principles and practice go hand-in-hand. The extent to which one or the other is made explicit on a course may depend o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter one: What about communication?

- Chapter two: What does one teach?

- Chapter three: How does one teach?

- Chapter four: Teaching materials

- Chapter five: Syllabuses in communication and media studies

- Chapter six: Resources and sources of information

- Chapter seven: Where do communication students go?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Teaching Communication by Graeme Burton,Richard Dimbleby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.