![]()

One

About Decay Photography

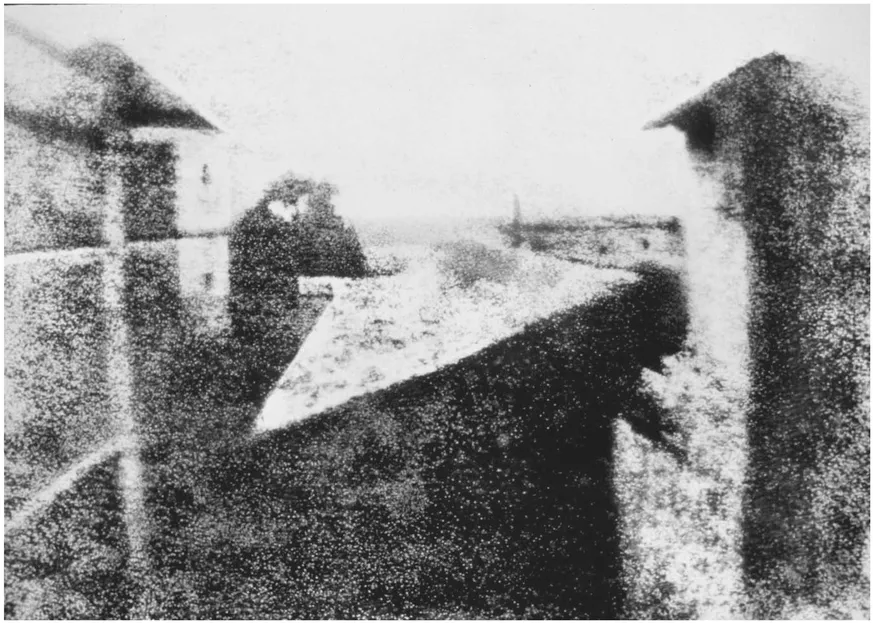

FIGURE 1.1 View from the Window at Le Gras. Long before photography was purportedly invented in 1839, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce created this image (which he termed a heliograph) in 1825

Arguably, decay photography has been around as long as photography itself. The first photograph ever taken by inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1825, “View from the Window at Le Gras” could conceivably also be the first photograph of urban decay. It simply shows a back alley in France. Coincidentally, this photograph is housed in Austin, Texas at the University of Texas and I have actually had the chance to view it in person.

Not much information is available on the actual history and derivation of decay photography. It’s almost impossible to pinpoint when it became an art form in and of itself rather than a form of photojournalism. You can find decay photography both on the front page of the daily newspaper and hanging in art galleries all across the world, but one thing is for sure, decay photography has become a viable form of fine art as well as a form of social documentation.

Decay photography means a lot of different things to a lot of different people. To me, decay photography is the ability to find the beauty in the blight. Finding interesting patterns, textures, and colors, and creating captivating compositions from scenes of collapsing architecture is a challenge that has started to attract the attention of many photographers and has even transformed people who were solely urban explorers (urbexers, as they refer to themselves) into photographers themselves. It’s funny to imagine a deteriorating building as being the catalyst for someone finding a new passion in life, but it has happened!

Decay photography is a medium that allows the photographer to document a moment in time, because every single minute the earthly elements of weathering and chemical reactions are changing sometimes seemingly unchangeable structures made from iron, steel, and concrete. Some photographers have even been known to return to the same

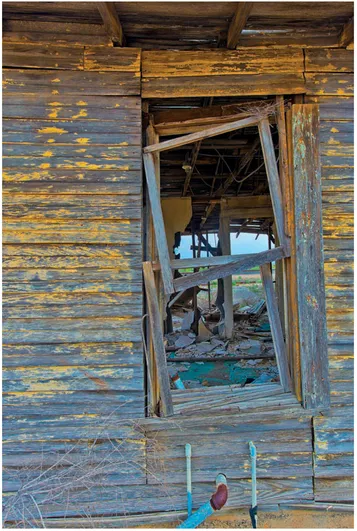

FIGURE 1.2 Putting together color and texture, and framing the image just right is what makes decay photography a challenging subject. Nikon D800 with Nikon 14–24 mm f/2.8G at 20 mm. 1/60 sec. @ f/6.3 ISO 100

FIGURE 1.3 The historic Stowe building at the West Bottoms area of Kansas City, MO. Nikon D70 with Tokina 19–35 mm f/3.5–4.5 at 35 mm (52 mm equivalent). 1/400 sec. @ f/6.3 ISO 200

scene for many years to document how time, weather, and even man have taken a toll on the landscapes and structures of an area.

It’s easy to find the beautiful parts of a city: the fantastic new skyscrapers gracing the skyline, the recently erected modern city buildings, and the hip high-rise condos are all designed to be pleasing to the eye; yet to some of us the shiny facades of these structures only solicit yawns. We are the urban explorers that cross over to the wrong side of the tracks to find the collapsing structures that may have once held magnificent interiors with chandeliers and ballrooms, the discarded industrial buildings where workers once toiled. We are the travelers that take the back roads to our destinations in hopes of discovering an abandoned dwelling where people used to live, work, and play. We stop and document the things left behind, sometimes wondering what these lives were all about, why they’ve gone, and what made these long lost people, these veritable apparitions, leave their possessions behind. We are the decay photographers.

Key photographers

Probably the first photographer to recognizably portray urban decay photography was Jacob Riis, although Riis’ goal wasn’t to find the beauty in the decay, but to portray the squalor in which people were living in the tenements in New York City. His photographs were ultimately used in a book called How the Other Half Lives, published in 1890. The darkness of the tenements ultimately resulted in him helping to pioneer the use of a flash in photography. Riis’ ultimate goal was to use his images as a tool for social change, but in doing that he also created some of the first urban decay photographs.

FIGURE 1.4 In this photo you can see the ground floor of the Stowe building as it appeared in 2004; since then the ground floor has been converted into a reception hall for weddings and looks very different. Decay photography can document the history of a building. Nikon D70 with Tokina 19–35 mm f/3.5–4.5 at 35 mm (52 mm equivalent). 1/125 sec. @ f/4.5 ISO 200

Flash forward about 45 years to the Great Depression. The Farm Security Administration, better known as the FSA, commissioned a slew of photographers to document the plight of the farmers that were suffering under the worst drought in American history. These photographers by definition weren’t rural decay photographers, but by necessity captured many photographs of rural decay. A few of these photographers were Dorothea Lange (although she was more well known for her portraits), Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein, and Carl Mydans; there were many more. As they documented the poor conditions of the farmers they were also unwittingly creating rural decay photography as well as urban decay photography by documenting the farm workers as they moved to the cities and urban environments.

In the 1970s and 1980s urban and rural decay photography had a bit of a resurgence, perhaps in part due to the fact that most buildings at that time were built in an earlier era, and due to the economic problems of the period, buildings were falling into disrepair. Unlike previous eras, however, the intention of many of these photographers was,

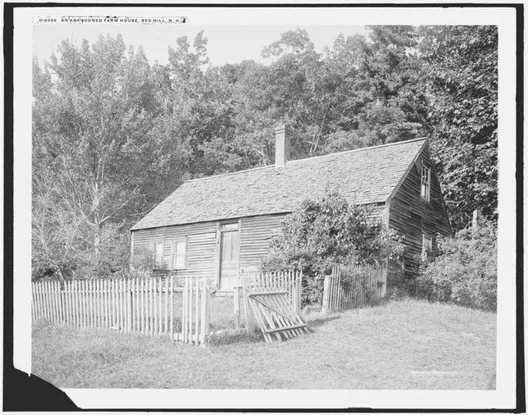

FIGURE 1.5 Photographers have almost always been attracted to photographing decay. This photograph of an abandoned farmhouse was taken circa 1906 in Red Hill, New Hampshire. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

for the first time, to create art rather than journalism or social change.

Edward Burtynsky is one of the photographers that looked at decay photography as an art form and preferred a more industrial climate over that of inner cities or rural communities. His favorite subjects were scrap piles, industrial wastelands, quarries, and any type of landscape that had been altered by industrialization. His photographs are vast, sweeping landscapes, usually shot at ultra-wide angles to accentuate the scene.

Another great photographer of this period is Camilo José Vergara. He is famous for what is known as rephotography, in which he would go back to the same place months and years later and document the changing landscape from the same

FIGURE 1.6 Signs, Yorkville, NY, by Arthur Rothstein. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, US Farm Security Administration

vantage point, using the same lens and film format. The result is the documentation of the change of the scene, be it for better or for worse. He also captured crumbling inner-city tenements, fallen buildings, and structures in disrepair. I think that, out of all urban decay photographers, his style is copied the most, even though the bulk of photographers probably don’t realize it. His style is very intuitive.

These days, with the advent of digital photography, there are hundreds of thousands of photographers out there documenting urban and rural decay, and making great art from it. At the same time, most major American cities are cleaning up and removing the infrastructure from urban decay. Just a decade ago most cities were rife with dilapidated structures, but most are disappearing, whether for safety reasons or to rid the city of what most people see as an eyesore; therefore, it is a good time to get out there and start shooting. Document what you can before these beautiful scenes of decay disappear for good, being replaced by shiny new modern buildings.

FIGURE 1.7 An image of urban decay from Washington, DC circa 1935, taken by Carl Mydens. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, US Farm Security Administration

Urban decay

Images of urban decay can be found almost anywhere that has been visited by man, both in and outside of cities. Oftentimes these scenes include sights of industrial ruin as well as exterior and interior shots of buildings that have fallen into disrepair. Abandoned homes, hospitals, hotels, industrial facilities, jails, power plants, and prisons are but a few of the many places that may serve as sites for scenes of urban decay. The key to finding these scenes is to keep a sharp eye open at all times. Whenever I’m traveling I instinctively keep my eyes open for interesting architecture and possible opportunities for photos of decay. It may take some time to train yourself to do this, but after a while it becomes second nature and you won’t even realize you’re doing it until you see a location.

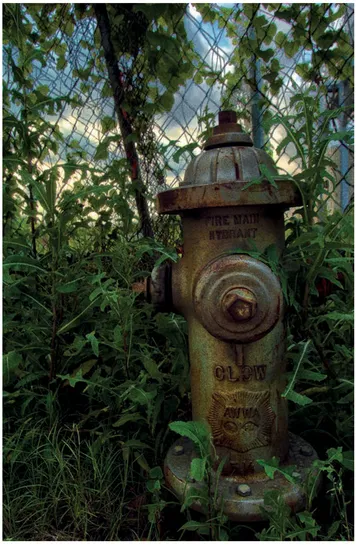

In urban decay photography there are lots of different subjects that can be utilized; the subject doesn’t have to be a falling-down building or a ravaged building interior. It can be something as simple as a fire hydrant, a piano that has been dumped in the middle of a roadway, or simply a vehicle abandoned in the street and left to rust. Old cemeteries are another place to get great decay photographs.

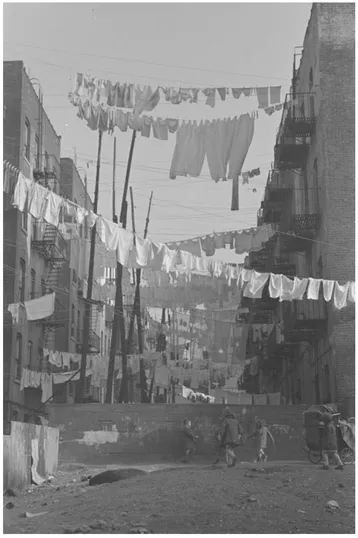

FIGURE 1.8 An early example of urban decay photography. An avenue of clothes washings between 138th and 139th Street apartments, just east of St. Anne’s Avenue, Bronx, New York, by Russell Lee, circa 1936. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, US Farm Security Administration

FIGURE 1.9 Even a simple fire hydrant sitting among the overgrown weeds of an abandoned construction site can make a good subject for urban decay photography. Nikon D2H with Sigma 17–35 mm f/2.8–4 at 17 mm (25 mm equivalent). 1/100 sec. @ f/5.6 ISO 200

To find great subj...