![]()

Part B

Nine Cities, Nine Sorrows

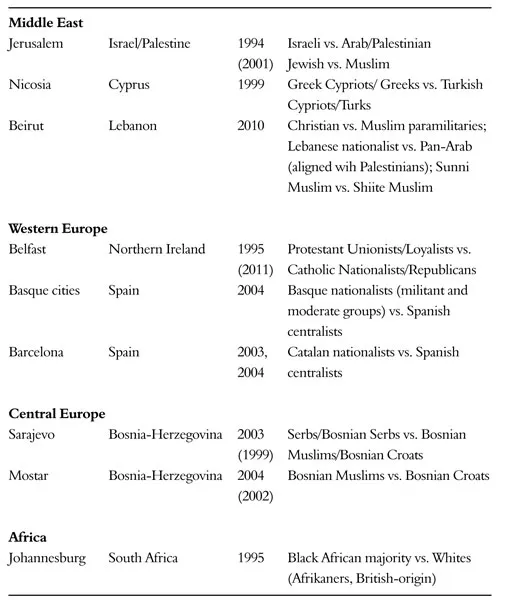

Each of the nine primary cities that I will examine (see table 1) has been, or currently is, challenged by deep and challenging questions arising from historic and contemporary inter-group conflict, and has been at one time or another part of political negotiations aimed at transitioning the city and society towards a more mutually co-existent future. The common ground upon which these nine cities stand is defined by urbanism, inter-group difference, and political transition. I selected the first three cases – Belfast, Jerusalem, and Johannesburg – in order to compare a city with unresolved political tensions (Belfast in 1995), a city amidst a political settlement (post-1993 Oslo Jerusalem), and a city amidst a successful political transition (post-apartheid Johannesburg). My study of Nicosia came about due to fortune, because I was invited to a negotiation forum there and made inside contacts. I chose the second set of case studies to focus on cities amidst transition – after a war in the case of Sarajevo and Mostar (Bosnia), and after the 1970s transition from Franco authoritarianism in the case of Spanish cities. The Spanish transition coming 20 years prior to the Bosnian one was an intentional feature of case study selection. I also focused on the Spanish cases because many observers view the Franco-to-democracy transition in Spain as effective and I wanted to explore this possibly more advanced case of inter-group co-existence.

The final and most recently studied case of urban polarization – Beirut (Lebanon) – encapsulates many of the complex and difficult aspects of urban nationalistic conflict and represents an appropriate culmination to this stage of my research agenda. The reader will note the substantially greater depth and length of the Beirut exploration. Whereas earlier cases are syntheses and re-formulations of previously published material and unpublished field research notes, the Beirut writing is entirely new, has not been published in any form, and is more detailed in its presentation of both analysis and personal observations. The Beirut case fully exploits my earlier experiences and understandings and at times revisits some of the themes developed in previous cases. Thus, the Beirut case is the most robust and multi-layered appraisal among the nine cities.

I also report, in Chapter 14, on a secondary set of cities to increase the comparative depth and breadth of the research project. These cases are effective examples of power-sharing (Brussels and Montreal) or, just the inverse, are deeply embroiled to this day in deep differences over group rights and obligations (Baghdad, Kirkuk, and Mitrovica (Kosovo)). The main source of information for this secondary set of cities is not interviews but published works by others that examine political power sharing options in these cities. In all, I explore a deep and diverse set of urban cases – running the gamut from cities having some stability of peace to ones moving tenuously and in fragile ways towards peace to others stuck in gridlock to ones in unstable and politically combustible environments.

The nine primary cities are distinct in their histories, cultures, and traditions, but they share a common sorrow – exposure to periods of intense and sometimes violent conflict. It is within this context that every day the people who live in these areas have had to struggle for co-existence. The extreme physical manifestations of hatred that these ‘abnormal’ cities have witnessed provide informative windows into the role of urban policy vis-à-vis ethnicity, and the ways in which people deal with each other in so-called ‘normal’ cities of North America, Western Europe, and elsewhere in the world.1 The walls and spaces that divide peoples in these famous polarized cities are present – in the backyards of America, but we don’t realize they are there or we don’t talk about them.

Understanding these cities helps us appreciate the role and position of cities and urban governance vis-à-vis two of most severe challenges of today – (1) inter-group conflict (how can different groups co-exist alongside one another in a constructive way?), and (2) democratization (how can transitions towards a democratic regime produce sustainable and constructive outcomes?)

Note

1. Danner (2009, pp. xvii–xviii) makes a similar argument, asserting that violence lays bare the underlying realities of politics and the structures of power. That the universal is discernable within the particular Walter Benjamin labelled as ‘monad’ (Gilloch, 1996, p. 35).

Table 1. Cities, region, year of primary on-site research,* and main conflict fault-lines.

* Dates of other visits are in parentheses

![]()

Chapter 4

Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina: ‘Urbicide’ and Dayton

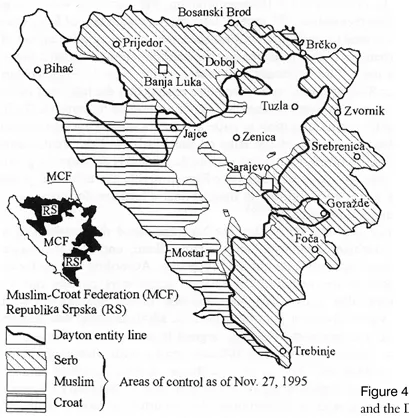

The ‘urbicidal’ siege of Sarajevo by Bosnian Serb and Serbian militias that completely blockaded and encircled the city lasted 1,395 days (from 2 May 1992 to 26 February 1996), killed 11,000 civilians, including 1,600 children, and damaged or destroyed 60 per cent of the city’s buildings. In my visit to the city in 2003, 8 years after the war, the political ‘solution’ and the ‘peace’ still had an imposed feeling. The Dayton accord of 1995 institutionalized a de facto partition of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The autonomous Bosnian Serb entity of Republika Srpska created by Dayton comprises 49 per cent of the country’s territory and lies immediately to the east of the city, a reward for its ruthless fighting machine. The city is now of markedly less ethnic diversity than before the war. The ‘peace’ in Sarajevo approximated what one finds when visiting a cemetery.

Is the absence of an armed border 4 years after war a good sign or a bad sign? Should its absence be treated as a sign of mutual tolerance or an indicator of an artificially imposed peace?

The boundaries between the Dayton-created Muslim-Croat Federation and Republika Srpska entities (in international speak, Inter-Entity Boundary Lines or IEBLs) are within the south-eastern part of the urban area and contain no checkpoints and no visible signs of differentiation, except for the Cyrillic written alphabet present in the Bosnian Serb entity. Indeed, in an affront to the logic of aggression, by 1999 there was new road-building to connect the two entities and the creation of ‘universal licence plates’ to facilitate automobile travel from one part to the other. Was not land and its control what the heinous 1992–1995 Bosnian war was all about? Another crossing nearby, although also without checkpoint, reveals who is sponsoring this reconnection. Electronic monitoring and transportation vehicles of NATO’s Stabilization Force (SFOR) were obvious and busy, contradicting the otherwise intended normalcy of the unmarked crossing. Do those now seeking connection believe that which was torn apart by war can be normalized 4 short years after slaughter? And is the absence of an armed border 4 years after war a good sign or a bad sign? Should its absence be treated as a sign of mutual tolerance or an indicator of an artificially imposed peace?

They were 15 and 14 years old when the war started. They are now kids with the wisdom, sadness and perspective of adults.

Sarajevo is the most emotional and wrenching urban environment that I have encountered. Jasmina Resulovic and Arnan Velic were 23 and 22 years old as the twentieth century closed. Jasmina is a short, round faced, bespectacled young woman with contemporary flare. Arnan is a lean man, almost gaunt, dark-featured and handsome. As Jasmina says, ‘I guess by our parents’ birth we are Muslim’. Both are architecture students at University of Sarajevo. They both stayed in the city during the 4 years of war, Arnan fighting in the Bosnian Army for five months, and Jasmina mired with her parents and other family in a high-rise flat near the front lines of hand-to-hand fighting. During the war, they attended abbreviated ‘war school’ in lieu of high school. Since the war, they and a few other students now run a ‘getting to know Sarajevo’ student project that offers tours of the historic and war affected city. I spend one and a half days alone with Jasmina and Arnan as they guide me around the city and I query them about the ‘indescribable’. They were 15 and 14 years old when the war started. They are now kids with the wisdom, sadness and perspective of adults. ‘We grew up during the war, but we don’t know when’, states Jasmina in a matter of fact way.

Figure 4.1. Kovaci (Martyrs’) Cemetery, Sarajevo.

Figure 4.2. Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Dayton Accord Boundaries.

Figure 4.3. Arnan and Jasmina.

Jasmina, Arnan and I stand for many quiet moments at the Vraca Monument on the hills overlooking Sarajevo. It is a remembrance of the power of brotherhood in the communist partisans’ successful crusade against fascism in World War II. Arnan finally speaks: ‘it’s unreal, it is like that war never took place; we learned nothing’. Their long stares at this monument are also probably due to this cruel fact: it was from within that monument that the heavy guns of the Serb militias were first fired from the hills at the Grbavica neighbourhood of the city below. Those militias and their guns spent the entirety of the war lodged within these walls which celebrate interethnic unity. For entertainment between gunfire, the militia men had erected a basketball backboard and hoop on one of the stone walls. Knocked off during their recreation are thousands of small letters of the names of partisan fighters commemorated on the hills above Sarajevo.

Figure 4.4. Vraca Monument, Sarajevo.

It is a different life now. ‘Everyone was equal during the war’, says Jasmina, ‘now money follows money’. And in a cruel irony, Arnan painfully describes how ‘we are looked down now by those who left during the war and now are back with new cars and clothes. Sometimes I just want to strangle them’. Jasmina’s mother is a teacher and now makes about one-third of her pre-war wages. Her underemployed father makes less than her mother. When Jasmina was able to work as a translator for seven days, she was embarrassed to take the wages back to her household because it was as much as her mother makes in one month. Jasmina describes her interest in a book Sarajevo: Wounded City, at 109 German marks an expensive purchase. While in a bookstore on Marshall Tito Street in the city, she asks the owner who can afford such a book these days. Jasmina recounts, ‘the lady said foreigners and those with the big cars. Funny, isn’t it?’.

Perseverance amidst challenge reveals the essence of who we are, scraped off of all the layers we put on it.

Arnan’s and Jasmina’s story is not one of only despair. Arnan asserts in an unpredictable, almost hopeful way, ‘we’re not afraid of trying things now. If we fail, we fail, it’s OK. There is so much opportunity now, not compared to before the war, but in life generally. It is short and one must make the most of it’. And, shockingly to me, it was not depressing during our time together to hear Jasmina and Arnan talk. By this I do not mean that it was cheerful but rather that hearing stories of how the human soul perseveres and matures is affirmative of life. Depression relies on the lack of feeling, and this was feeling. Perseverance amidst challenge reveals the essence of who we are, scraped off of all the layers we put on it. These emotions and feelings are precious parts of life to witness, so much so that I must be careful not to want these experiences as one wants material things. Instead, I need to be grateful, always be receptive to them, for the special things that they are and what they can teach us about being human. There is hope in despair, a spirit amid gloom. The simple ability to persevere, live, cope, and grow amidst hatred is proof of light and love. Without the surrounding darkness, how would we know that we could illuminate each other and ourselves? Connecting to the hardship of another does not discourage, but makes one happy because it roots you in compassion.

After a day and a half of touring war-stricken Sarajevo and tired and satisfied, I return to my hotel. At the reception desk is a gift T-shirt – of the cheap tourist type showing a leggy woman welcoming the viewer to Sarajevo – and a note from Arnan saying this is something that may help me remember my visit. I went back to my room, lay down and was flooded by the pain and the utter goodness of people living in inhumane places and times. A boy, now man, who has lived through hell thinks of giving to an American visitor. The kitschy nature of the gift makes it even more poignant. Sarajevo’s, Arnan’s, and Jasmina’s story contains a radically different plane of emotion that overwhelms and connects one to another.

How, pray tell, do I describe photographs of this place to my six-year-old son? Should I?

In 1999, I look out of the window of a sandwich store at the fresh cobble-stoned street of the old city and view a well-dressed proprietor sweeping the front of her clothes store, with a public water fountain (so valuable during the war on the city) running freely nearby. This is not the way it was in the war, when Sarajevo became a scene of a crime, a rape, and devastation. It was an affront to humanity and rationality. Blown off limbs, punctured heads, humiliation, playgrounds and soccer fields turned into cemeteries because these were areas that hillside snipers couldn’t see, the famous ice rink from the 1984 Winter Olympics shelled and afire, building after building shattered and burnt. How, pray tell, do I describe photographs of this place to my six-year-old son? Should I? Elvir Kulin, working in a small bed-and-breakfast inn I stay at during my 2003 visit, describes to me discreetly and in hushed tones how he watched, as an 18-year-old Bosnian army conscript, old men being shot dead in the back by enemy combatants.

‘Urbicide’ – the attempted killing of a city – was part of a secret plan designed in Belgrade (Bublin, 1999). In smaller towns of Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH) with strategic value to Serbia’s territorial ambitions, local territorial forces of Bosnian Serbs were to provoke an incident; then paramilitary groups from Serbia would make raids and ‘cleanse’ the territory of non-Serbian residents. The Army aligned with Serbia would then roll in its armour and create a buffer zone around the conquered territory. In larger urban centres such as Sarajevo, neutralization actions included artillery bombardment and sniper fire, shelling of non-Serbian residential areas, blockades of traffic, propaganda campaigns, surprise attacks, and the destruction of vital urban structures. The result of these military tactics was the besieging and holding hostage of the city for almost 4 years.

Figure 4.5. Parliament Building, Sarajevo.

At the beginning of the siege in 1992, aggressor forces had surrounded Sarajevo with 260 tanks, 120 mortars, and vast numbers of rocket launchers, anti-aircraft machine guns, snipers and machine guns. In contrast, the city’s defenders were left with minimal arms for protection. This is so because early in the war the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA) evacuated its troops and arms from the Tito Barracks in the city’s centre and consolidated its forces with the Serbian and Bosnian Serb militias on the surrounding hillsides. Throughout the war, mortar shells of 82, 120, 150, and 250 millimetres shelled the city. Snipers using semi-automatic guns were deployed in tall buildings within the occupied Grbavica neighbourhood of the city, where they stayed for much of the war. Every day the city was hit by some 4,000 shells on average; among the targets were hospitals, schools, mosques, churches, synagogues, maternity hospitals, libraries, museums, open-air and sheltered food markets, and any place where people stood in line for the limited supplies of food, bread and water.

The war led to wide-ranging destruction of physical capital and housing stock. Over 1,400 monuments of culture in Bosnia were either destroyed or damaged, of which 440 were totally razed to the ground (Bublin, 1999). Libraries, museums, institutes, schools,...