1 Framing the issues

Complexity, uncertainty, risk and necessity

Introduction

The conjoining of the terms learning and sustainable development in the title of this book and its companion reader Key Issues in Sustainable Development and Learning: a critical review may seem quite natural to some readers but very much less so to others. It is certainly possible to be employed as a sustainable development professional, conducting environmental impact assessments for example, without having any interest in learning beyond the personal need to acquire information and skills. It is also possible to be a learning professional, organising vocational courses for unemployed adults perhaps, without ever having given much thought to sustainable development, either personally or professionally. It is our intention to argue that, nevertheless, learning and sustainable development are inextricably entwined. At the same time we hope to lay bare the issues surrounding this claim, and so enable readers to judge its worth for themselves.

Immediate difficulties concern the question of definition. Both terms have been defined in a number of different ways at the theoretical level, for practical purposes by policy makers, and by professionals in everyday usage. Dobson (1996), for example, has recorded over 300 definitions of sustainable development. Both terms also relate to and/or overlap with other terms (for example, lifelong learning, adult education, human resource development, training, sustainability, conservation, environmental management) in ways that are often ambiguous, unclear, and/or contested.

Definition is, of course, important. However, because a major purpose of this book is to seek to further develop definitions of both (lifelong) learning and sustainable development, each by reference to the other, we see definition as a core process of the book as well as a provisional starting point. It seems most appropriate, therefore, to set precision aside and begin with working definitions which are as inclusive as possible. Thus, for the time being we shall take learning to include all the learning that a person does between birth and death. One important consequence of this is that schooling is not excluded, and neither, therefore, are any consequences that schooling may have for what is learned in adult life, or for our abilities to learn. A second consequence is that work by others which is based on narrower definitions of learning, or which while clearly concerned with it does not explicitly use the term, is not excluded from consideration. Hence ideas as diverse as those of OECD (1996), which sees lifelong learning primarily as a means to economic competitiveness, and of Lauder and Brown (2000), who argue for the fostering of ‘collective intelligence’, lie within our field of interest, and both these works are considered in the companion reader.

In a similar way sustainable development is treated here, at least initially, as a set of contested ideas rather than as a settled issue. This set incorporates many different, and indeed competing, definitions of both sustainable development and sustainability. The extent of contestation surrounding these terms is illustrated by, for example, the work of Sachs (1991) who sees the linking of environment and development as a ‘dangerous liaison’, and Hopkins et al. (1996), who see sustainable development education as the focus of an ‘international consensus’. As with lifelong learning, extracts from both are examined in the companion reader.

Exploring linkages

(Lifelong) learning and sustainable development have a number of aspects in common.

First, both are policy objectives. It is clear from Hopkins et al. (1996), for example, that these authors see sustainable development as a desirable, and indeed necessary, goal. In taking this view they are being entirely consistent with the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED, 1987 – and see chapter 11 of the companion reader) – which first thrust the notion of sustainable development into the limelight, and which so powerfully influenced the development of Agenda 21 (UNCED, 1992). Promotion of lifelong learning, and its universalisation through the creation of a learning society, has been put forward as a necessary policy goal in response to the existence of a Risk Society (Beck, 1992; Adams, 1995; Rosa, 2000; Strain, 2000 – and chapters 1 and 4 of the companion reader).

As policy objectives, sustainable development and learning both respond to perceptions that

- Scientific and technological advances have caused the human species to have more control over, and be less at the mercy of, its environment than ever before

- These same advances have increased actual risks to humans, habitats, ecosystems and some other species because of the ways in which our scientific and technological interventions are managed, mismanaged or abused, and from uncertainties about the environment’s responses to them

- There is increased powerlessness in the face of risk’s now seeming pervasiveness, although as both Redclift and Le Grange note (chapter 1 of the companion reader) this may be a phenomenon of more concern in developed economies

- Within the human species the once apparently solid elements from which individual and group identities were constructed – class, gender, seniority, ethnicity, nationality and so on – have become increasingly fluid and unreliable.

Second however, both lifelong learning and sustainable development have been promoted as policy instruments, typically for the end purpose of enhancing economic competitiveness at both national and corporate levels. For example, the UK’s Sustainable Development Education Panel (2001) has justified its efforts as necessary to long-term national competitiveness and companies such as Shell (Jones, 1997) have claimed sustainability as central to their business strategies. The European Commission (1996), OECD (1996) and the Group of Eight Industrialised Nations (1999) have all placed lifelong learning at the centre of competition policy, and there is evidence (Hamilton, 2001) to suggest that there is growing corporate interest in the commercial value of being a ‘learning organisation’ (Senge, 1992; Argyris and Schön, 1996 – and see companion reader).

A third similarity between the two terms is that both have become slogans (Field, 2000; Redclift, 1987; Sachs, 1991; Stables, 1996; 2001a,b) which can sometimes be used to give an impression of substance or coherence where little exists. Thus, both may often be viewed as bandwagons, to which more or less unlikely causes can be hitched opportunistically. It is probably fair to say that even their staunchest advocates can sometimes appear confused about whether (lifelong) learning and sustainable development are means to ends or ends in themselves. They are not unique in this as such problems readily arise where, in the pursuit of narrow initiatives and intentions (eg, educational programmes of numeracy, literacy and ICT) one can lose sight of the point of the entire exercise (ie, the ultimate liberal purpose of an education). Of course, it may be that in some quarters such confusion is welcome, or at least found to be of some use. Nevertheless, the ends/means distinction is significant. As Sterling (2001:15–16) notes, the choice is about doing more of the same, or doing something radically and deeply different.

Fourth, both sustainable development and lifelong learning are widely conceived as being incapable of operationalisation solely through the actions of governments (Carley and Christie, 1992; Field, 2000). They necessarily involve participation by citizens, and probably by other groups such as businesses and voluntary organisations. Social inclusion, and the key role of individuals, tends to be theorised as at the heart of both. Ehrenfeld (1995: 183) notes:

The ultimate success of all our attempts to stop ruining nature will depend on a revision of the way we use the world in our everyday living when we are not thinking about conservation. If we have to conserve the earth in spite of ourselves, we will not be able to do it.

and Martin writes:

All the government, scientists, experts, organizations, laws, and treaties in the world will achieve nothing unless there are free-thinking and freely-operating individuals in a position to make their own decisions about the future of their natural environment.

(WWF, 1996: 27)

However, we would argue that such similarities between two currently quite fashionable terms are symptomatic of a deep and problematic coherence between important and enduring aspects of the social and natural worlds. We set out to show through this book and its companion volume that exploring this underlying reality has potential to add value in practical ways to society’s ongoing efforts to sustain, learn, develop and live. One initial problem is that the ways in which language is used to bring clarity to some issues can often obscure others, and this is explored in detail in Chapter 3. In a similar way, in Chapter 2 we exemplify the linkage between sustainable development and learning showing congruence and interconnectedness, and the issues this raises for each.

However, it seems important at the outset to explore the meanings of some of the key parameters of our discussion.

Society, nature, environment

Munasinghe and Shearer (1995) use the term ‘biogeophysical’ to describe the nonhuman natural world. It is important, however, to realise that, for all the social construction of reality, the laws which govern such biogeophysical processes are not negotiable by humans. They are ‘natural’ and, in this sense of the word, Nature itself is beyond human threat. If the Earth is one day devastated then the processes of physical destruction and recovery will follow such natural laws, both those known by humans and those not, regardless of whether the destructive agency is a random collision with a comet or asteroid, or the planned lunacy of a tyrant. In this context ‘conserving Nature’ makes little if any sense.

Of course, when we use the word ‘Nature’, we tend to be thinking of the ecology of the planet rather than the blind calculus of biogeophysical processes. Because of this, we imbue Nature, understood broadly like this, with meaning and sometimes, as in the case of ‘Gaia’ (Lovelock, 1979) or the ‘Earth Mother’ and the related ideas of some ecofeminists (Spretnak, 1990; Mies and Shiva, 1993; Merchant, 1990; Gough, 1997), with human characteristics. In fact, as Ross (1994 – and companion reader) has shown, it has been common in Western societies to attribute two contradictory sets of characteristics to Nature, seeing it on the one hand as a tooth and claw battle for the survival of the fittest, and on the other as an intricate self-sustaining, collaborative web. This dissonance is deeply rooted in popular culture and will be familiar to devotees of, for example, The Lion King, an animated film in which the interests of ‘The Great Circle of Life’ are served by lions eating antelope but not, apparently, by hyenas eating lion cubs. Nor should the attribution of meaning to Nature be necessarily despised, since it may have useful social consequences; but that is to stray too quickly into the realm of value, values and value judgements, which are discussed in detail in Chapter 12.

The important point for our discussion here is that biogeophysical laws describe the environment of Mars just as well as the environment of Earth: they describe an environment. Only by adding in the meanings we attach to our surroundings do we come to a description of the environment – that is, ours, the one we live in. It should be noted that meanings here refer not only to sentiments (fondness for a particular landscape, place or species, for example) but also to apparently robust concepts such as resource. Whether an object qualifies as a ‘natural resource’ depends on two things: whether we can do something with it, and whether we want to – and both of these are crucially properties of the human subject not the environmental object.

Natural laws, then, are givens: but the given-ness of the environment can and should be questioned. For example, the jungles of Borneo are a hostile and threatening environment for an ill-prepared European, but reassuringly familiar and nurturing for the Penan people. In time, the European might learn the indigenous population’s skills of survival and come to a different view; or might import technologies to transform trees into furniture. The Penan might come to prefer a lifestyle in towns with libraries, restaurants and television – or not.

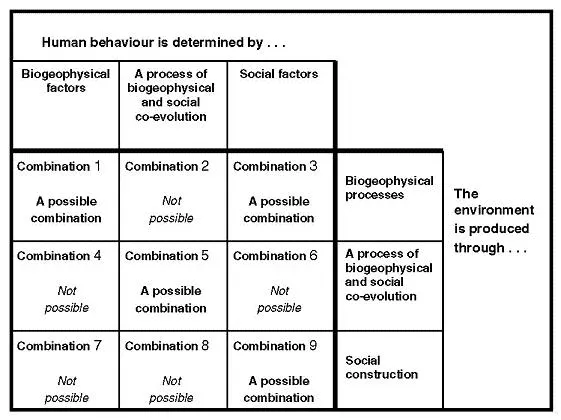

What emerges from this discussion, however, is a point of central importance in understanding our topic: that there is a distinction to be made between what society, nature and the environment physically are on the one hand, and how we think about them on the other. Figure 1.1 shows a set of possible ways of thinking about the relationship between society and the environment.

How the relationship between society and the environment is perceived depends on responses to two inter-related questions. These are

- How far is the environment determined by human behaviour?

- How far is human behaviour determined by the environment?

Figure 1.1 Possible combinations of views of the relationship between society and the environment.

It is possible to offer a number of pairs of logically consistent answers to these, while other pairs of responses are logically impossible. Such is the flexibility of the term ‘sustainable development’ that it can be pressed into service by adherents of any of the logically possible combinations. These different combinations also have different implications for the role of learning.

In Figure 1.1, the pair of views (Combination 1)

- Human behaviour is determined by biogeophysical factors

- The environment is produced through biogeophysical processes

seems consistent with the sociobiological view that all social behaviour has a biological basis (Wilson, 1975). However, this position has been critiqued on a variety of grounds. For example, Redclift (1987) argues that it is reductionist, commits the naturalistic fallacy of supposing an identity between what is ‘natural’ and what is ‘good’, claims universal characteristics for human behaviour while ignoring the diversity of human cultures and ideologies, and has unpalatable impli...