![]()

1Outlining a psychology of the image

INTRODUCTION

In contemporary culture images play a significant role in influencing our understanding of ourselves, those around us, and the environment we live in. Our everyday experiences ranging from the banal to the enriching are replete with images. Before leaving our homes in the morning we find ourselves checking to see whether we look right (i.e. displaying a good or at least an appropriate ‘self-image’). We decorate our houses with pictures, photographs and other images both for the pleasure they bring us and for what they ‘say’ about our lifestyle. When we hear a piece of music that captures our attention, we might talk of an image coming into our minds, and often when we are buying something we suspect that the decisions we make have been influenced by the images we have seen promoting that product. Hardly a day goes by without politicians, theologians and social commentators warning us of the dangers of image ‘over-exposure’, while all the time making sure their own images are presented in line with the appropriate conventions.

On the one hand we experience a considerable range of diverse images from the external world, and on the other our mental life is saturated with, and constituted by, internal images, impressions, ideas and associated representations. Richard Kearney (1988) suggests that we are seduced by the implicit ideologies of the latest media cult or craze, and seem to have entered an age where reality is inseparable from the image, and where

our understanding of the world is preconditioned by the electronically reproducible media of television, cinema, video and radio . . . where fantasy is more real than reality, where the image has more dignity than the original.

(Kearney 1988: 252)

What we mean by understanding is itself conceived of as mental representation, one of a number of ‘image related’ metaphors of conceptual knowledge. When psychologists talk of cognitive representations and mental imagery they implicitly invoke constructs of the mental image, occasionally ‘picture-like’ and often presupposed on the image or model of the proposition (image as idea; idea as image). This ubiquitous and polysemous term (image) serves many functions in quite diverse contexts: it means many different things to different people and remains a rather elusive term in psychology. Nonetheless, the word ‘image’ provides an orienting concept for one aim of this book, namely to consider a range of theoretical perspectives which may bring us to a better understanding of the role of images in contemporary life.

In this book I aim to examine relationships between external images – for example what we are presented with on billboards, television, cinema or on computer screens – and internal images or imaging processes which make it possible for us to recognise, understand, reflect on or otherwise comprehend images. The desire to do so arose initially out of recognising the conceptual distance between theories in media and communication studies which focus upon image production and audience reception, and ideas in psychology where the aim has been to understand the relationship between mental life and behaviour. At first glance, there appears little connection between theories about images we have in our heads and corresponding ideas on the production or effectiveness of images encountered in everyday life. Our understanding of the social world is surely impoverished without addressing, or at least questioning, the relationships between external images, broadly conceived, and internal cognitions (at least those described as image based).

Given the wide range of topics which concern images, developing or at least outlining a psychology of the image may strike the reader as a rather grandiose enterprise. The aims of this book are, however, more direct and hopefully realisable. The first is simply to consider a number of research areas which contribute in significant ways to our understanding or conceptions of images. A second aim is to critically consider theories within the social sciences which inform our understanding of image production and recognition. A third aim is to reflect upon identifiable tensions between internal and external image domains, thereby highlighting future directions that a distinct psychology of the image might take. The topics in the book are organised into three general themes. The first focuses upon internal images including perception, mental imagery, sound imagery and dreams. The second theme addresses the interdependent nature of internal and external images over three chapters, with topics including images of the developing self, social identity, image-reputation and the gendered image. This last topic, the portrayal of gender through images, acts as a particularly useful link into the third theme of the book, external images. Here, two chapters focus upon the role of mass-media images (covering film, television and electronic contexts), one on the photographic image. Essentially, the final theme of the book focuses on topics where the processes of image production and recognition seem to be quite separate from internal image processes. The remainder of this introductory chapter considers whether it is possible to conceive of an orienting theoretical framework for a psychology of the image, given the very diverse nature of image study. We can begin with some comment on the definition or rather definitions of image employed throughout the text.

A linguist might easily describe the word image as a polysemous expression, (i.e. a word or phrase possessing multiple meanings) and one with many richly related connotations and derivatives: the imaginary, imago, imagination, imagery, imaginable and so on. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) provides at least a dozen definitions of the word image ranging from the commonplace to the obscure and the highly technical. For example we have image defined as ‘an artificial representation of the external form of any object, especially a person’, or again as ‘a mental representation of something’. We can contrast these with ‘a visible figure, an appearance, an apparition’ or ‘an undesired signal frequency heard as interference [a radio term}’. We can also find definitions which distinguish the term on the ‘internal/external’ dichotomy outlined earlier with image described as:

1a mental representation of something (e.g. a visible object), not by direct perception but by memory or imagination; a mental picture or impression; and

2a concept or representation created in the mind of the public of a particular person, institution or product – public-image.

Possibly it is the terminological diversity of the word image (and its associated derivations) which underlies the conceptual distance found across disciplines with interest in the topic (from whatever angle). At the same time, the polysemous nature of the term image provides an opportunity for articulating a conceptually coherent theory of the image: an integrative construct reflecting a psychologically informed theoretical approach to the study of the image (or images).

At the risk of pre-empting elements of the framework outlined below, three particular definitions of the word image will be clarified and elaborated on. These reflect the focus on internal mental imagery, external culturally produced images and self-constructed images which span the ‘internal—external’ dichotomy. This classification is used in the first instance only as a starting point – a position which reflects some of the definitions and concepts associated with the word image in the current literature.

Each distinct domain of the word image takes two forms, a static or object-like aspect and a process or dynamic element. In the first domain, where the study of internal images is paramount, the static or object form can be defined as a mental representation of any object or event. The process counterpart, defined as the imagination, will be restricted to those actions of imagining or forming a mental concept of something that is not actually present. This encompasses both ‘rationalist’ forms such as scheming, hypothesis testing and impression formation and also ‘non-rational’ or less conscious activities such as dreaming.

The second meaning of image would emphasise external attributes and representations. Specifically, image here is defined as a representation of something to the mind by speech, writing or graphic description broadly defined. Note the significance of the phrase ‘to the mind’; i.e. images are external entities which might be understood as intentional ‘utterances’ by some known or unknown generalised ‘other’. In order to fulfil the criteria of being an image, in a sense they have to ‘project’ something or other. They say something to us, we can recognise what they are ‘saying’ and we respond to their ‘signification’ in appropriate ways. Correspondingly, where we come to consider process elements of this domain, the dynamic nature of television, film, music and radio operate in distinctly different ways to more static objects such as bill-posters, photographs, pictures, sculptures and postage stamps.

A third conception of the image will be developed with reference to domains where the ‘internal’ meets the ‘external’. Here we focus on how the private finds expression in the public, as well as how the public underpins, reproduces and constrains, the private. Examples of the former would include the numerous ways we use fashion to display different versions of ourselves (or self-images); instances of the latter might be where members of the royal household take care in promoting an appropriate public image. In this third broad definition of the term image, although there are obvious examples of the ‘static’ versus ‘dynamic’ distinction (personal ads columns versus image as movement and ‘style’ on the fashion catwalk) the theoretical outline described below may help elaborate and extend this initial terminology. For now, these three definitions or broad domains of the image serve only to situate different academic, technical and everyday uses of the term.

FRAMING A PSYCHOLOGY OF THE IMAGE: PEIRCEAN SEMIOTICS

Outlining a psychology of the image which encompasses diverse domains can be realised through a reading of semiotics, particularly the work of the American semiotician C. S. Peirce. Semiotics, as the science of signs and sign-systems, provides a way of describing and explaining the structures and procedures of communication systems (in their broadest sense). A semiotician is just as likely to be interested in the symbol-system used by non-human primates as in the codes, rules and algorithms of machine-generated ‘artificial intelligence’. Semiotics is

concerned with the formulation and encoding of messages by sources, the transmission of these messages through channels, the decoding and interpretation of these messages by destinations, and their signification. The entire transaction, or semiosis, takes place within a context to which the system is highly sensitive and which the system, in turn, affects.

(Saussure 1974: 69)

Historically, semiotics emerged as part of the structuralist movement in the early twentieth century which in part explains the debate over whether semiotics is part of the study of language or language (and linguistics) subsumed within semiotics. As semiotics is critically concerned with the production, recognition and transmission of signs, those who study images have often adopted a semiotic perspective. As will become clear, we find semiotic theories of the sign employed in photography, film and television, art and aesthetics, advertising and computer interface design.

At the risk of oversimplification, the relationship between semiotics and symbols, signs, emblems, images or any such related representation can be summarised as the process of signification: the study of how signs come to represent or ‘stand for’ anything at all. Saussure (often described as the originator of semiotics) pointed out that the signs and elements of any language acquire meaning not because there is some ‘real’ connection between words and things in the world, but as part of a system of relations. The sign for the word ‘donkey’ only means what it does with reference to all those signs in the language that do not mean ‘donkey’. Likewise, the use of the colour red in traffic lights only means ‘stop’ with reference to the system of elements and relations within which it acquired meaning.

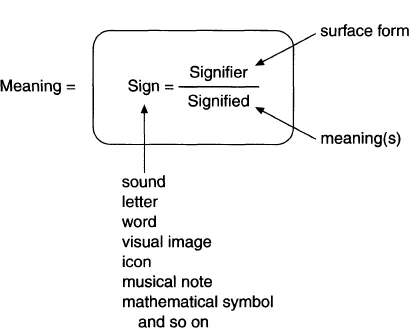

An important aspect of Saussure's conception of the sign was the indissoluble relationship between the components which made up any given sign and the nature of meaning (as in Figure 1.1).

A number of points are worth emphasising, particularly as this form of Saussurian semiotics has often been misunderstood or glossed over in psychology. First, there are two senses of the word meaning as it refers to the sign in Figure 1.1. There is the global sense of meaning (Meaning in the figure) which is addressing the question of how it is possible that any given sign has the potential for being read or understood at all (i.e. analysis of the sign such that the possibility and potential for a given meaning can be recognised). The other sense of meaning is that which is conventionally associated with the sign in question (e.g. ‘donkey’ is a sign that is made up of a number of letter characters (its surface form d-o-n-k-e-y) while its meaning is the horse-like four-legged creature we might find in the countryside.

Figure 1.1 Semiotics and meaning

Second, semiotics is concerned with any sign-system. Although the semiotic approach is often associated with structural linguistics, the reason why it has much broader applicability is that any element which forms part of a meaningful system of communicative exchange can be analysed as a sign. If semiotics is defined as the discipline that studies all meaningful exchange, following Frawley (1992), this encompasses text, visual media, literature, art as conventionalised aesthetic meaning, cultural rules and codes of behaviour, dream interpretation and non-verbal communicative gestures. Arguably, semiotics can be used as a conceptual instrument in the three domains of the image described in this book. In fact, for radical semioticians there are few areas of social-cultural practice which do not lend themselves to sign-system analysis (e.g. see Sebeok (1994) on this point).

This brief résumé of structuralist semiotics reflects the European approach outlined by Saussure and others during the early to mid-twentieth century (see Hodge and Kress (1988) for an insightful critique of traditional semiotics). Slightly earlier, the American philosopher C.S. Peirce outlined an approach to semiotics as a response to a number of mid-nineteenth-century problems in logic and epistemology. In particular, Peirce was concerned with understanding the nature of knowledge and mind, i.e. under what conditions can we distinguish between what is ‘real’ from phenomena and things ‘out of the mind’, and whether (and how) natural science, specifically logic, can provide fundamental tools for a philosophical analysis of meaning. Hookway (1985) notes that in Peirce we encounter the ‘mind-numbing claim that the elements of experience and reality may be classified into firstness, secondness and third-ness’ (p. 2) with all other complexities and conceptions reducible to this tripartite essentialism. While post-structuralism might find such a ‘metaphysics of categories’ misplaced, Peirce's analysis may have considerable significance for a psychology of the image, a point we will return to in the final chapter.

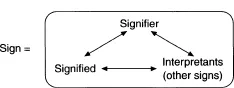

Consider for now his ideas on the nature of signs. Rather than simply claiming there was an indissoluble relationship between signifier and signified for any given sign, Peirce introduced the idea of the interpretant: an additional element of sign comprehension determined by the sign itself. The sign is not simply a relationship between the signifier (surface form) and signified (its meaning), but also includes a third element, highlighting the observation that every sign determines an interpretant (Figure 1.2). To paraphrase Sebeok's (1994) analysis of this development, with the sign for the English noun ‘horse’, interpretants could include gee-gee, pony, stallion, and even the word heroin. There are no limits to the number and form of interpretants, ‘signs and discourses on and of, signs which overlay another sign’. As Peirce notes, a sign is anything ‘which determines something else (its interpretant) to refer to an object to which itself refers (its object) in the same way, the sign becoming a sign, and so on ad infinitum’ (1966: 272). And any paraphrase or extended discourse on any sign ‘will enrich comprehension of the object it represents, as will also its interlingual translations and intersemiotic transmutations’ (Sebeok 1994: 13).

Figure 1.2 Peirce's conception of the sign

How the concept of the ‘interpretant’ fits into the signifier-signified relationship of a sign can be understood if we pay close attention to what Peirce termed ‘scientific intelligence’. Peirce went to great pains to emphasise that the idea of an interpretant does not presuppose some kind of subjective cognitive state or mind (i.e. the interpretant is not necessarily a person). Consider a sign such as the marked and exposed bark of a tree signifying the presence of deer in the forest. First, the act of recognising the stripped bark as a sign at all highlights the idea of one thing signifying another, the notion that the first thing (the bark) is understood or interpreted as a sign of a second (deer). The link between the sign and what it signifies is mediated through subsequent thoughts which serve as interpretants for the sign. These thoughts are themselves made up of other signs (our thoughts, associations, reflections are made up of words, images, signs). Second, it is only because we know how deer behave in the woods when feeding that we see the marks on the tree as a sign of the presence of deer. The point, as Hookway (1985) stresses, is that signs contribute to our learning from experience by mediating between reality and our cognitio...