![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Since Aristotle, science (and biology in particular) has become fractionated into many disciplines, which have been further subdivided into specialisms as formalisms and concepts have diverged progressively. As a result, communication between scientists has become more and more difficult. Although science specialisation reflects our increasing scientific knowledge, fractionation due to specialisation has become a serious issue now that our planet is under global pressure. Indeed, the direct (e.g. exploitation, destruction) and the indirect effects (e.g. anthropogenic climate change) of human activities on our planet, and their global effects on biodiversity and ecosystems, require the integration of many different branches of science.

Many scientists have provided evidence for the strength of having a multidisciplinary and holistic view to resolve global problems. One of the best examples is perhaps given by the discovery of the theory of continental drift by the German meteorologist Alfred Lothar Wegener (1). His theory resulted from a synthesis of many different scientific disciplines (e.g. geology, biogeography, palaeoclimatology). The scientist stressed in the preface of his book that it was essential to develop a global view of the planet (1), so as to examine what Alexander von Humboldt called the Unity of Nature. Indeed, the earth should be viewed as a system composed of functional units that exchange energy and matter by physical, chemical and biological processes. Functional units are intricately coupled.

Eduard Suess introduced the word biosphere and Wladimir Ivanovich Vemadsky developed the concept. The biosphere interacts with the geosphere (all other non-living functional units), creating a unique planetary ecosphere, and subsystems of significant importance for mankind such as water quality, soil fertility and fisheries, Lovelock and Margulis (2) proposed that organisms interact with their abiotic environment on earth, creating a self-regulating, complex system that contributes to maintain suitable environmental conditions for life. Even if the theory remains controversial (3, 4), many authors have stressed the need to develop an integrative science devoted to the study of the response of the biosphere to global change. In this book, I will try to adopt such a global approach and integrate as many scientific fields as necessary to better understand how biodiversity is organised in space and time and how it is influenced by climatic and environmental variability, as well as global change.

Our planet has entered a new era, the Anthropocene (5), where human activities are interfering with the natural functioning of the planetary ecosphere. Interference occurs in the atmosphere through an increase in greenhouse gas concentrations such as carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, in the hydrosphere (oceans, seas, estuaries, lakes, ponds, rivers) through pollution, eutrophication and acidification, and in the biosphere through habitat fragmentation and destruction, species introduction and over-exploitation. As a result, biodiversity has been altered at an unprecedented level (6). Biodiversity, a term coined by Walter G. Rosen in 1985 and popularised by Edward O. Wilson in 1988, has been defined in the Convention on Biological Diversity in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 as 'the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within

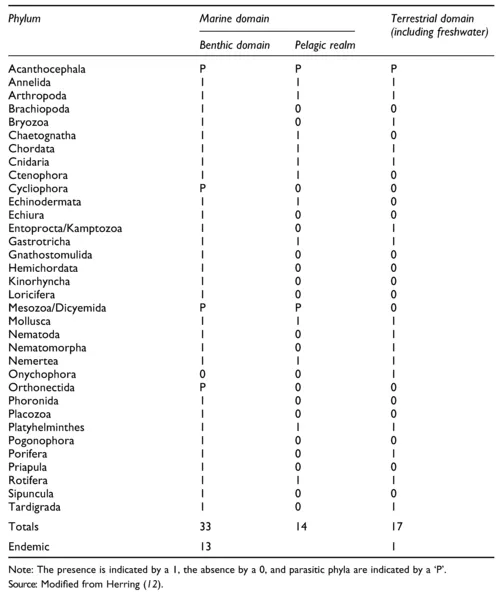

Table 1.1 Phylum composition of the marine benthic and pelagic realms in comparison to the terrestrial domain.

species, between species and of ecosystems'. Biodiversity is currently studied at four main levels of organisation: the genetic, molecular, organismal and ecological levels.

1.1 Biodiversity from the land to the ocean

About 1.8 million species have been described in both the terrestrial and the marine realms (7). Because of a lack of a central catalogue and the existence of a probable important fraction of synonymous names, the number of currently valid species is around 1.2 million (8). Assessments of total biodiversity range between 3 million and 100 million species (9), with many species undoubtedly waiting to be described or even to be discovered (10). For example, insects are among groups in which new species are reported every year (11). Mora and colleagues (8) estimated that the global number of eukaryotic species may be ~8.7 ± 1.3 million, of which 2.2 ± 0.2 million may be marine. Their results suggest that 86% of terrestrial species and 91% of the marine species remain unknown to science.

At the phylum level, marine metazoan biodiversity is by far greater than terrestrial biodiversity (Table 1.1). On the total number of metazoan phyla (a total of 34), 33 are present in the sea. Table 1.1 shows that huge differences exist between the pelagic and the benthic realms, however. All phyla are present in the benthos, whereas only 14 are detected in the pelagic realm. Only 17 occur in the terrestrial realm, with only one endemic.

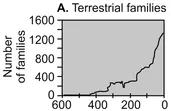

At the species level, marine biodiversity does not seem high, despite the fact that the oceans cover ~71% of our planet. Estimates from May (7) suggest that only 15% of all inventoried animal and plant species alive are marine. Benton (13) provided evidence that in contrast to the marine realm, the diversification process is more rapid on land. In the oceans, examination of well-known marine fossils suggests that the diversification shows rapid radiation followed by a plateau, which suggest that equilibria may exist (Figure 1.1). In contrast, in the terrestrial realm, the study of fossil records reveals exponential diversification from the Silurian to the present.

Widdicombe and Somerfield (14) also stressed other important differences between the marine and the terrestrial realms. Marine biodiversity is ancient. Chemoautotrophic prokaryotes and photosynthetic cyanobacteria appeared 3 billion years ago and eukaryotic cells 2 billion years ago. Marine biomass per unit area is much smaller than terrestrial biomass. The terrestrial domain is mainly two-dimensional (the third dimension being between 0 and 100 in), whereas the marine domain is three-dimensional (mean depth of 3,500 m). Only a fraction of the marine domain can therefore perform photosynthesis. In addition, marine primary producers are mobile in contrast to their terrestrial counterparts.

1.2 Classification and census of marine biodiversity

1.2.1 Classification

Biodiversity has been subdivided many times, and research on life classification continues. Carl Linnaeus classified biodiversity into domains and kingdoms, with those divided into phyla, classes, orders and families up to the species level. Different classification schemes have been proposed. The first classification proposed by Carl Linnaeus divided life into two groups: Vegetabilia and Animalia (15). More recently, biodiversity was divided into five kingdoms (16): (1) Monera (prokaryotic organisms); (2) Protista (unicellular eukaryotic organisms such as dinoflagellates, coccolithophores and foraminifers); (3) Fungi; (4) Plantae (Metaphyta or multicellular eukaryotic plants); and (5) Animalia (Metazoa or multicellular eukaryotic animals). In 1977, a phylogenic classification scheme based on ribosomal RNA sequences divided biodiversity into three kingdoms: (1) Eubacteria; (2) Archaebacteria; and (3) Eukaryota (17). The most recent division of life is due to Cavalier-Smith (18, 19). The molecular biologistdistinguished two empires (Prokaryota and Eukaryota) and six kingdoms: (1) Bacteria (Eubacteria and Archaebacteria), the only member of Prokaryota; (2) Protozoa; (3) Animalia; (4) Fungi; (5) Plantae; and (6) Chromista (e.g. diatoms, haptophytes and dinoflagellates). The kingdom Bacteria is subject to the International Code of Bacteriological Nomenclature, the two 'zoological' kingdoms, Protozoa and Animalia to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, and the three 'botanical' kingdoms (Plantae, Fungi, Chromista) to the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (18).

Figure 1.1 Pattern of life diversification for the last 600 million years.

Source: Redrawn from Benton (13).

1.2.2 Census of biodiversity

Table 1.2 shows the catalogued and estimated biodiversity of the different kingdoms in both the terrestrial and the marine realms. At the species level, all kingdoms are more diverse in the terrestrial realm.

Because scientists have inventoried living organisms for 250 years, many species have been described many times and many different names have frequently been attributed to the same species. Accounting for the problem of synonyms, Mora and colleagues (8) estimated that there are ~1.2 million described species and that ~70% of these species are animals, and especially insects. They estimated that 193,756 marine species have been labelled. This estimate is smaller than others that ranged between 250,000 (20) and 274,000 (21). Mora and colleagues assessed that about 2 million species remain to be described in the marine environment.

Bouchet (22) synthesised the number of marine species known per taxonomic group and estimated ~230,000 described species (Table 1.3). Many new species are discovered each year....