![]()

1

Manager-Subordinate Trust Relationships across Cultures

PABLO B. CARDONA, MICHAEL J. MORLEY, AND SEBASTIAN REICHE

Introduction

Trust is one of the key determinants of performance in business organizations and a necessary outcome of true leadership (Kouzes & Posner, 1993). As a result, trust has been an important construct in the social sciences and has also received increasing attention by organizational researchers (Colquitt et al., 2007; Mayer et al., 1995; Whitener et al., 1998), especially in the field of manager-subordinate relationships (Brower et al., 2000; Dirks & Ferrin, 2002). While past research has offered multiple perspectives to advance our understanding about the nature of trust relationships in an organizational context (for a comprehensive review, see Bachmann & Zaheer, 2006), scholars have also singled out some of the rather unanswered questions that deserve further attention.

One area of intense debate concerns the relative status and importance of trust as cause, effect, or interaction (Rousseau et al., 1998). For example, despite convincing conceptual arguments, existing research provides mixed evidence for the influence of trust on work-related behaviors and outcomes (Dirks & Ferrin, 2001). These findings may stem from a limited consideration of asymmetric perceptions of trust between social actors in the literature (Schoorman et al., 2007). Studying the dynamics of trust formation in dyadic hierarchical relationships thus promises to refine our understanding of what drives trust and how trust benefits the individual in organizational settings. In addition, the existing literature on trust has traditionally adopted a largely Western focus, thereby often ignoring how, and to what extent, trust formation may vary in other cultural contexts. However, initial evidence suggests that cultural differences, especially concerning the relationship between the individual and the collectivity that prevails in a society, affect individuals’ propensity to trust (Huff & Kelley, 2003) and their evaluation of potential trustees (Doney et al., 1998). Understanding the role of culture in trust formation is thus important to advance our knowledge about trust dynamics and establish the potential significance of contextual influences on its development.

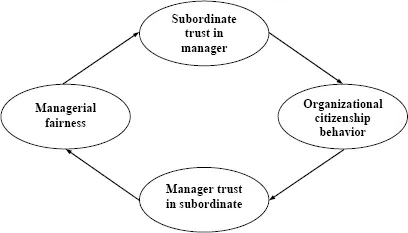

Drawing upon existing evidence that views leader–member exchange relationships and trust building as cyclical, iterative, and mutually reinforcing processes (Blau, 1964; Brower et al., 2000; Graen & Scandura, 1987), we propose that managerial fairness will influence subordinates’ trust in managers, which in turn will lead subordinates to engage in organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Based on this behavior, managers will judge subordinates’ trustworthiness and then reciprocate with fairness. Whereas we view trust as an affective state (McAllister, 1995), we consider fairness as a specific managerial trustworthy behavior perceived by subordinates and OCB as a specific behavioral response of subordinates perceived by managers.

Theory and Model

The increased scholarly interest in the concept of trust has led to a wealth of different definitions and conceptualizations of trust (e.g. Bachmann & Zaheer, 2006; Mayer et al., 1995; Rousseau et al., 1998). Although these definitions typically vary in their specific content, most researchers acknowledge that trust comprises an intention to be vulnerable to the actions of a referent based on the expectation that this referent will behave in a certain manner (Colquitt et al., 2007). Trust is also viewed as a multidimensional construct (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002) and a central focus in the literature has been an attempt to differentiate between an affective and cognitive dimension of trust (Lewis & Weigert, 1985; McAllister, 1995). Whereas affective trust is reflected in an emotional bond between actor and referent that may cause the referent to demonstrate concern about the actor's welfare, cognitive trust commonly entails a belief or expectation that the referent is reliable, has integrity, is predictable, and/or will act in a fair manner (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002). In the crosscultural research program reported in this book, we limit our attention to affective trust for two reasons. First, given our desire to examine the reciprocal nature of trust formation in manager–subordinate dyads, our focus is on the direct, affective relationship between a trustor and a referent rather than more general beliefs or expectations about a referent's competence, ability, etc. Second, implicit to the conceptualization of cognitive trust are certain behaviors, such as fairness, that lead to a conceptual overlap with the behavioral antecedents and outcomes of trust that we explicitly examine in our research. As a result, we define trust as an affective state that entails an expectation about a referent's genuine care, concern, or emotional reciprocation.

Both the development of leader–member exchange relationships and the development of trust have been described as cyclical, mutually reinforcing processes (Blau, 1964; Graen & Scandura, 1987; Zand, 1972). According to these models, the behavior of each player influences the other in an iterative fashion (Brower et al., 2000). In this vein, managerial fairness serves as a key behavior to enable exchanges with subordinates (Konovsky & Pugh, 1994) and has received much research attention as an antecedent of trust (Brockner et al., 1997; Pillai et al., 1999). Based on these initial behaviors on the part of the manager, subordinates are likely to hold a belief about their managers’ future intentions or behaviors (Lewis & Weigert, 1985). These expectations will influence subordinates’ trust in them and in turn lead subordinates to act accordingly (Mayer et al., 1995; Rousseau et al., 1998). An important behavioral outcome of subordinates’ trust that has been discussed in the literature is OCB (Colquitt et al., 2007; Dirks & Ferrin, 2002), defined as a job-related behavior that is discretionary, is not formally or directly recognized by the organizational reward system, and yet promotes organizational functioning (Organ, 1990). As a result of this subordinate behavior, the manager will make judgments about the trustworthiness of the subordinate and will respond with comparable trusting behavior. This will reinforce subordinates’ initial expectations and initiate continuous trust building (Zand, 1972). Hence, we contend that subordinates’ assessments of managers’ trustworthiness are occurring in parallel to managers’ evaluations of subordinates’ trustworthiness (Brower et al., 2000). To fully understand leader–member exchange relationships, we thus need to study both subordinates’ trust in managers and managers’ trust in subordinates.

In sum, the model conceptualizes the transition between behaviors and affective states in trust formation. We argue that there is a reciprocal relationship between fairness as a managerial behavior and subordinates’ OCB and that these behaviors both initiate and result from affective trust between manager and subordinate, thus leading to manager–subordinate trust building. Conceptually, subordinate trust in manager and manager trust in subordinate therefore act as mediators in the relationship between fairness and OCB. Figure 1.1 illustrates this model.

Testing the Model

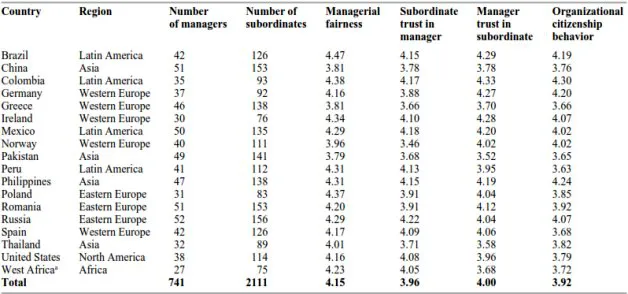

To test our model set out in Figure 1.1, we collected quantitative data from manager–subordinate dyads across six different regions, covering a total of 18 countries.1 Subsequently, we engaged in a second round of qualitative data collection. In this round, we employed semi-structured ethnographic interviews, focus group interviews, and a Delphi panel, the basic purpose of which was to aid interpretation and contextualization of the data.

Table 1.1 provides details on the sample sizes and the key variables’ mean scores per country, as well as the corresponding region.

Figure 1.1 The reciprocal model of hierarchical trust

Table 1.1 Sample size and mean scores on the main variables per country

Note

a Data collected from Nigeria and Ivory Coast are combined in the analyses under the label of West Africa.

Participants were recruited from different organizations to represent as wide a variety of sectors/organizations as possible, aiming for a maximum of 10 percent of respondents from the same company for each country included in our study. Our sample contains managers and subordinates working both in the public and in the private sector and includes both middle and top managers. Questionnaires were developed in English and then translated into the local language, using a back-translation method (Brislin, 1986). Each country collaborator subsequently verified the quality of the translation before starting the data collection.

We employed two separate sources for data collection—a manager and a subordinate questionnaire—in order to reduce the risk of common-method bias. Managers were contacted directly by the researchers in each respective country and then asked to identify up to three subordinates to whom they would forward the subordinate survey. In the manager survey, managers were asked to rate their subordinates’ OCB and their trust in their subordinates. In the subordinate survey, subordinates rated both the perceived fairness of their managers’ behavior and their trust in their managers. All data were collected through either study-and-pencil questionnaires or online surveys. Our choice of survey medium was driven by the technical capabilities and preferences of the respondents being surveyed. The layout of the two surveys (study pages and web pages) was identical. Recent research has compared traditional study surveys with online data collection and found no effects of the survey medium on response characteristics (Simsek & Veiga, 2001).

In total, 2140 manager surveys were administered, which yielded 741 manager responses (a 34.6 percent response rate). All 741 managers forwarded the subordinate survey to three of their subordinates each, resulting in 2111 subordinates (a 96.3 percent response rate) completing the questionnaire across all 18 countries. The final sample ranges from 75 to 156 dyads per country (see Table 1.1). The 741 managers in our sample had an average age of 39.8 years and an average organizational tenure of 8.9 years. In addition, 69.5 percent of all managers were male, 44.3 percent were middle managers and 50.1 percent occupied a top-management position. The 2111 subordinates in our sample had an average age of 34.4 years and on average had been with the organization for 6.4 years. In addition, 53.4 percent of subordinates were male. On average, the managers and subordinates in our study had worked together for 3.9 years.

Measures

All variables were measured using multi-item, five-point Likert scales. Items were placed in random order in the questionnaire.

Managerial fairness. Based on the literature on organizational justice (e.g. Folger & Konovsky, 1989), we developed a three-item scale of managerial fairness (1 = “totally disagree” to 5 = “totally agree”), including “My supervisor always fulfills his/her promises” and “My supervisor deals with me honestly.” Building on the notion that fairness measures should be specific to the setting in which the study is being conducted (Greenberg, 1990), our items were specifically written for the manager-subordinate context that formed the basis of the present study. The three items were averaged to create a scale score (a = .81).

Trust. We used a four-item measure adapted from McAllister's (1995) affective trust scale to operationalize subordinate trust in manager (1 = “totally disagree” to 5 = “totally agree”). Two example items are “If I shared my problems with my manager, I know he/she would respond constructively and caringly” and “I can talk freely to this individual about difficulties I am having at work and know that he/she will listen.” We averaged all four items to create a score for the subordinate trust in manager scale (a = .83). In order to measure manager trust in subordinate, we developed a new scale adapting the items used to measure subordinate trust in manager (1 = “totally disagree” to 5 = “totally agree”). Two example items are “I feel secure about the decisions that this subordinate makes at work” and “We have a sharing relationship. We can freely share our ideas, feelings and hopes.” Again, all four items were averaged to create a scale score (a = .81).

OCB. The literature does not agree on the dimensions that best represent organizational citizenship behavior. Smith et al. (1983) first measured the construct and proposed two dimensions: altruism and general compliance. Later on, research added other dimensions to the OCB construct. Coleman and Borman (2000) suggested that citizenship dimensions can be grouped in three categories: directed toward specific individuals, directed toward the organization as a whole, and task-oriented OCB. In this study, we focus on subordinates’ OCB that is directed toward the organization as a whole. Our rationale for examining this dimension of OCB is based on the contention that employees tend to perceive actions by agents of the organization as actions of the organization itself (Levinson, 1965). Since managers are responsible for several duties that affect employees’ organizational membership, such as per-formance evaluations or training, managers serve as organizational representatives and will elicit specific attitudes and attributions toward the organization from their employees (Rich, 1997). Citizenship behavior directed toward the organization can thus be viewed to form an integral part of the manager-subordinate relationship, and recent research has shown manager–subordinate trust to be related to organization-directed rather than individual-directed citizenship behavior (Brower et al., 2000). To measure this dimension of OCB, we used six items from Lee and Allen (2002), including “This subordinate defends the organization when other employees criticize it” and “This subordinate expresses loyalty toward the organization.” The six items were averaged to create a scale score (a = .82).

Control variables. We controlled for a number of variables to improve our model estimation. We first controlled for the period of time the manager and subordinate have worked together in a hierarchical relationship. Relationship duration was self-reported by the manager and measured in years. We also controlled for the age difference between manager and subordinate. Accordingly, we measured manager and subordinate age in years and computed a difference score. Similarly, we controlled for the possibility that trust building may vary depending ...