- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Where do we come from? Where are we going? These are fundamental questions, which the human race has asked itself for centuries.

Presenting a brief and accessible overview of contemporary scientific thought, Creation is an imaginative and poetic exploration of the origins of the universe. WIllem Drees assesses the religious and philosophical impact of scientific theories of evolution and the natural world, and examines the changing relationship between us and our planet.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Scene 1

When time was not yet

There was a time

when there was no time,

when time was not yet.

when there was no time,

when time was not yet.

Of old humans have seen the Sun and the Moon, the planets and the stars. The telescope, invented in 1608 in Middelburg in the Netherlands, revealed new details within our solar system, such as craters on the Moon and the moons of Jupiter. The telescope also enlarged our world: we came to live in a world of stars, with the Sun being one star among many.

A hundred years ago our horizon moved again further back: the stars that could be seen form together a galaxy, a disc with stars assembled in a few spiral arms. Our galaxy was not unique, but merely one of billions of galaxies, each with billions of stars. New technologies have moved the horizon back further and further. Each time we look further away, the universe turns out to be larger than previously thought.

In 1676 Ole Rømer measured the velocity of light by checking carefully when the moons of Jupiter passed the planet in front or on the far side. He concluded that light travels at a finite speed. The speed of light, about 300,000 kilometres per second, is a huge velocity for us, but so are distances in the universe. Light from the Sun takes eight minutes to reach the Earth. Light from the next nearest star takes a few years.

On 23 February 1987 astronomers saw the explosion of a star in a nearby galaxy, the Great Magellanic Cloud. Old news – the explosion had taken place about 200,000 years ago. Light from other galaxies takes even longer. Current technology allows us to notice objects so distant that light has taken billions of years to reach us: we see the universe as it was in the past.

An eternal universe?

Is there a limit? Or will we always look further away, and thus also farther back in time? How far we can see depends on our technology. But is there in principle a limit, or will there be ever more galaxies, beyond any horizon?

It is now thought that one cannot always look further away. To support this idea, one does not need a telescope; it is enough to be aware that it is dark at night. Imagine that one is in a forest. Some trees are nearby; others further away. We are close to one tree, which blocks our sight in that direction. If it is a small forest, with not too many trees, we might be able to see through the forest to the open field. But in a large forest one will not be able to see beyond the forest; in all directions one will see trees. Similarly in a universe: if it were filled with galaxies and if it were sufficiently large, galaxies would have been in our line of sight in all directions. Stars would have been in our sight in all directions. Hence, the sky should be as bright as the surface of a star. Day and night the sky should be as bright as the Sun. But it is dark at night. Hence, the universe cannot be filled with stars until infinity. This argument arose at the end of the seventeenth century. It is called Olbers’s paradox. Every night the darkness proves that the universe cannot be infinitely old and infinitely extended.

The Big Bang theory confirms this view of the universe. On the basis of observations and well-tested theories cosmology has made a reconstruction of the history of our universe. This history encompasses about fifteen thousand million years. The figure is not very precise, since it is hard to be sure about distances in the universe. However, whether it is twelve or twenty billion years, current knowledge is that the universe with all the galaxies we see began billions of years ago and has been expanding since. In later sections, we will come back to the development of the universe. Here we will reflect on this notion of a ‘beginning’.

A beginning in time?

One might think of the beginning of the universe as one thinks about the beginning of a work of art. At some moment in time it was made. Time may be imagined as the ticking of a clock, an infinite extension of moments. At one of those moments my life started, over a thousand million seconds ago. Long before that the Earth was formed. At again an earlier moment, some fifteen thousand million (109) years ago, the universe began.

If it started at some point in time, what preceded the universe? This question arises naturally upon such an approach. Before the work of art, there were the artist and her materials. Before my conception there were my parents. What was there before the universe?

This question was already raised in a different form in antiquity. Augustine, one of the major theologians in early Christianity, around 400 CE discussed the question what God was doing before God created the world. If you see creation as the beginning of the world, what was the Eternal One doing that infinity of ages before there was a world? Augustine first makes a joke, effectively saying: ‘Then God created Hell for those who ask such questions.’ But then, Augustine attempts to deal seriously with this question.

Augustine argues that the question is wrongly posed. The question what God was doing before creating the world, assumes that one can meaningfully speak about ‘before’ even when there is no world. This assumes that time is unrelated to the existence of a world. But time is connected to movement: the pendulum of a clock, the rotation of the Earth, the frequency of an atomic oscillation. If there is no clock ticking and no Earth rotating, how could we then say that time passes? Time assumes movement and hence matter. Augustine understands time, to use religious terms, as an aspect of creation and not as an attribute of God. If earth and heaven are not there yet, time is a meaningless notion. Augustine thus concludes: ‘If there was no time before heaven and earth, why then ask what Thou were doing then? For when there is no time, there is no “then”.’

A beginning of time?

Augustine rejected the idea of creation in time; time was something that came into being with creation. This is the kind of solution that contemporary cosmologists are seeking as well when they develop theories about the universe as a whole. Time is a notion that is related to material processes. In the very early universe, processes were different, and hence the notion of time was too. Perhaps, ‘time’ is not a well-defined notion when we approach ‘the beginning of time’. Rather than a sharp boundary, a moment when the initial push was given, there may perhaps have been a twilight, like the transition between day and night.

It may be that reality was different then. Or the problem may be ours, due to our inability to describe the situation well. Stephen Hawking, a cosmologist, uses the image of the north pole as an analogy. Everywhere on Earth one can point ‘north’. Except when standing on the north pole; there all directions are ‘south’ (or ‘up’ and ‘down’, but ‘above our heads’ is not what we mean by ‘north’). On traditional maps, the north pole is not a point but a line, the upper boundary of the map. Nonetheless, the north pole is a regular point on Earth – there too the horizon is around us in all directions. The Earth is slightly curved, just as everywhere else. It is our concept ‘north’ which is useless there. Hawking argues that ‘time’ is no longer a useful concept when we seek to describe the early universe. That is not a tragedy, nor does it suggest that there is ‘another side’. Rather, it is a limitation of our language. A concept that is useful for many purposes need not be applicable everywhere.

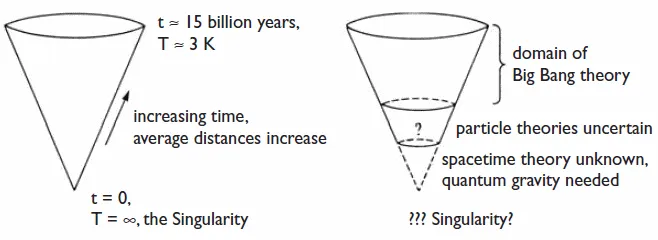

There are various other views. They all wrestle with the concept ‘time’. This is not a problem in ordinary life. The problems arise when one extrapolates back, in the context of the Big Bang model, until about 0.000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 1 second from the (apparent) beginning. The image has been that the Big Bang model describes our universe as expanding from an initial state of infinite density and temperature. However, this model is only reliable to the extent that the physical theories assumed are well developed and tested in the laboratory. Cosmologists are just like historians or archaeologists who seek to understand the past. They go backwards from our time and place, and somewhere will enter less well-charted terrain. The closer we get to the initial state, the more this is the case. In that sense, the Big Bang theory is not about the Big Bang, but about the development of the universe since a slightly later moment.

Figure 1 On the left the Big Bang model is depicted as a cone, with each horizontal slice representing the three-dimensional universe at a given moment of time. On the right the major uncertainties are stressed.

Note: (t stands for time; T for temperature)

To extend the domain further, theories about matter (quantum physics) and about space, time and gravity (general relativity theory) have to be integrated. Such an integration has not been achieved yet, though there are various ideas and proposals. Some speculative theories describe a universe with an ultimate boundary; other ideas suggest that our universe has arisen out of a different, ‘preceding’ reality. Such ideas are hard to test. We cannot recreate in a lab the conditions of the very early universe, but these ideas can be tested to some extent; a good theory should explain the development of our universe.

Perhaps the boundary of our knowledge will be moved further back. Perhaps almost all these speculations will turn out to be untenable within a few decades, with only one generally accepted theory about the first fraction of a second remaining. The way it seems to be now, paradoxical as it sounds, is that we have to do with ‘a time when time was not yet’, a phase of the universe when our notion of ‘time’ was not applicable. And if ‘time’ was not yet applicable, we are confronted with a beginning that was perhaps not the beginning, a first fraction of a second, which perhaps should not be called the first fraction of a second.

Though the new understanding of time would be forged in order to grasp ‘the beginning’, the ensuing understanding of reality would apply at all moments – and thus affect deep down our understanding of time and history. Cosmology challenges us to explore alternative views of time and reality, and thereby to free ourselves from a way of thinking which comes so naturally to us, namely the view that everything happens in time.

Scene 2

Mystery

The time

when there was no time

is a horizon of not knowing

a mist where our questions fade

and no echo returns.

when there was no time

is a horizon of not knowing

a mist where our questions fade

and no echo returns.

Then,

in the beginning,

perhaps not the beginning,

in the first fraction of a second,

perhaps not the first fraction

of the first second,

our universe began

without us.

in the beginning,

perhaps not the beginning,

in the first fraction of a second,

perhaps not the first fraction

of the first second,

our universe began

without us.

Will we ever be able to answer all questions concerning the early universe? The way I see it, science will be able to move back the horizon. We will see further, and hence differently. Our horizon might shift, but I believe that science will not remove this ‘horizon of not knowing’. There will always be ‘a mist where our questions fade, and no echo returns’.

A creation story begins with the beginning, but we do not know our reality as a film shown to us from the first scene onwards. Our situation resembles the predicament of archaeologists. We find traces and clues – and seek to understand the past. In that process, we answer questions and pass on other questions.

An architect who designs a building decides to use concrete. He has, we hope, knowledge of the forces that this concrete will be able to withstand. If someone would ask why the forces are as they are, the architect might refer us to an engineer who studies material sciences. This engineer should be able to inform us about experiments and the relevant theory, about the wear and tear of the materials concerned, and their relations to chemical bonds between the various materials. Perhaps the engineer even knows from which geological deposit the sand and cement have been taken. However, if you go on asking how those layers came to be there, the engineer will refer to a geologist. The geologist can tell a story about the erosion of mountains and sedimentation of sand and stones by rivers. Perhaps the geologist can discover that the sand used was part of a particular mountain range, and perhaps even that the same material was already deposited on a sea floor before. However, if one continues by asking where the silicon and oxygen come from, the chemical elements making up sand, the geologist will have to say that these were there when the Earth formed. For further questions, he will refer to the astrophysicist. And the astrophysicist can answer many questions, about the formation of elements out of hydrogen in the interiors of stars and during supernova explosions, and the way these elements are distributed in the universe and may get included when a solar system forms (see scene 4). However, this explanation assumes that there is already hydrogen as the material out of which stars are formed. When we go on with ‘historical’ questions we come to theories about the earliest stages of the universe, to the turf of the cosmologist.

This, in a nutshell, is typical of science. Scientists answer questions belonging to their province of expertise, while passing on other questions, about the things they take for granted in their own work. In the end, two types of questions remain. There are persistent questions about fundamental rules: Why does matter behave the way it actually behaves? Why are the laws of nature the way they are? What is matter? There are also persistent questions of an historical kind: Where does everything come from? How did it all begin? Such questions arise again and again when a sequence of questions is pursued. They are questions at the boundaries of science, ‘the horizon of not knowing’. Scientists can explain much, but that does not get one around these questions. The horizon moves, but is not removed.

Some people have attempted to answer such questions in a different way, by referring to our own existence. If we had not been there, we could not pose such questions. The universe is as it is, since that is the kind of universe in which we can exist. If the universe had been slightly different, life as we know it could not have come into existence.

That life would not have come into existence in a universe which was different seems to follow from various thought experiments. If one makes a mathematical model, one can also see how the universe would have developed if certain conditions and parameters had been different. What if the universe had slightly larger mass, or a slightly higher velocity at the onset of the expansion? What if the electron were a tiny bit heavier than the actual one? An electrical force which is smaller, or stronger compared to gravity? Why not space with two dimensions rather than three? And so on. All kinds of variations can be tried in our models. Such modifications, even small ones, can be shown to have major consequences, at least in the context of such models.

An example. The universe as we know it seems much larger than we need for our kind of life. We do not need much more than a solar system. And if we want to be generous, one galaxy with some hundred billion stars is large enough for us. Could the universe, then, not have been much smaller? The size of the universe seems pointless, wastefully abundant for a creator interested in life, and especially in conscious and responsible life such as humans. But is the size really pointless? If there is to be enough time for the formation of the heavy elements (see scene 4) and for the evolution of life (see scenes 5 and 6), the universe has to exist long enough – but then it also has to be large enough, since the longer the universe exists, the further light has travelled. Also, in order to be big, the universe needs sufficient mass. According to current scientific models, a universe with the mass of a single galaxy would expand for only one month before collapsing again. Life could not have developed.

Let us assume that our universe is indeed ‘just right’ for our kind of life. Does that have a deeper meaning, for instance a conscious choice picking those conditions that allow for humans? Does this provide a clue for faith in a creator intending humans to be?

In discussions on the universe there has been talk of ‘anthropic principles’. The choice of terminology is problematic, for it is not specifically about a universe in which humans (Greek: anthropoi) can exist, but about a universe in which a planet such as ours with the right kind of materials has sufficient time to bring forth life through evolution. Thus, it might be more appropriate to speak of a ‘biotic principle’ rather than of an ‘anthropic principle’.

Besides, humans also experience all kinds of misfortunes in this universe. A classic example is the buttered toast falling upon the floor with the buttered side down. A colloquial expression for the pessimistic mood is Murphy’s Law: If things can go wrong, they will. Careful analysis shows that the same conditions which allow for the emergence of human life, which optimists have appealed to in speaking of ‘anthropic principles’, are also those that make buttered toast fall from human tables upside down. Thus, perhaps there is an ‘anthropomurphic principle’ at work.

Upon closer inspection, we are not dealing with a well-defined ‘principle’, but rather with the realization that there might be a mix of circumstances hospitable to us. Thus, one might speak of ‘biotic coincidences’. The question then is what significance might be attached to those biotic coincidences.

Perhaps it is a matter of selective observation. If we were to live in a train and look out of the window, we would notice that railroad barriers are always closed. What a pity for those that stand waiting there; those cars will never get across. That is of course nonsense; we see closed barriers since we look at the world from within the train. That the conditions in our part of the universe are just right for us could be a claim of a similar kind, a consequence of selective observation. Where and when the conditions are different, we will not be and hence we will not observe such regions.

Another possibility is that coincidences that seem as if they could have been different, will be shown to be a consequence of a further developed theory. Since the discussion on ‘anthropic coincidences’ emerged, this has happened already to some extent. A new model was proposed, the inflationary universe. According to this model, the early universe went through a phase of extremely fast expansion. This model skilfully combines standard insights about matter and the Big Bang theory, and explains some features which are otherwise arbitrary, such as the homogeneity of matter and radiation in the observable universe – a feature previously explained by appealing to an ‘anthropic principle’.

Thus, even with respect to properties of the universe our puzzlement and our current questions may well be answered by future theories. At the same time, new questions emerge in the context of new theories. For instance, the inflationary model does not explain why the universe is such that inflation happens; some assumptions are always made. The reach of explanation is impressive, but explanatory successes do not exclude further questions. Again and again, questions emerge at the limits of scientific understanding.

Questions remain even if physics and cosmology agree one day on a complete theory, a theory explaining all known phenomena in a unified, coherent way. Imagine, a single article, a single formula answering all our questions. But the article is on a piece of paper; the formula cons...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Introduction

- A creation story

- Scene 1

- Scene 2

- Scene 3

- Scene 4

- Scene 5

- Scene 6

- Scene 7

- Scene 8

- Scene 9

- Scene 10

- From Now On

- Notes and literature

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Creation by Willem B. Drees in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.