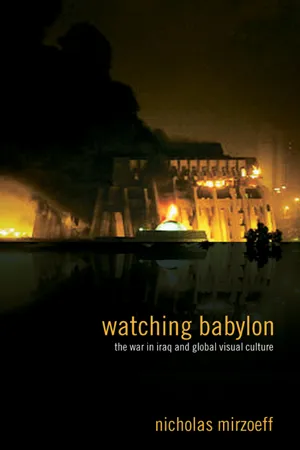

![]()

Section 1: Babylon, Long Island

Watching war, an activity to which we have become accustomed since the rise of global television, is a curious phenomenon. Of all viewing experiences, it is the most intensely “live,” in that it exists to witness the extinction of human life. Yet, like soldiering itself, it is for the most part an exercise in tedium. The 2003 war in Iraq raised the experience to new heights, saturating channels that only a few years previously had covered the stock market with similar non-stop enthusiasm. The constant updates, announcements of breaking news, switches to live press announcements and the circulation around the various correspondents and fixed cameras available reinforced a sense that this watching was present tense only. The strategy of “embedding” reporters with military units provided a means of identification for the American television viewer with the live images, even when there was very little to see. In contesting this visual narrative, it is necessary to begin by refusing this apparently transparent link to the remote site of warfare. Such images are legible for US audiences by virtue of the traditional film and television format in which an opening panoramic shot of a city skyline establishes the general location, followed by a gradual zoom in by the camera to reveal the star or hero of the piece. Such careful geographical locating of the viewer is now accomplished by the popular jump cut – an edit that “jumps” from one location to the next – a function that is compressed into the “live” news link. All this spatial and temporal jumping creates an idealized “American” viewpoint that has no specificity. So this section takes its time by refusing to jump into the image until a place from which to watch the war has been identified.

The place of watching has become elusive because, as we saw in the Prologue, modern anti-spectacle dictates that there is in fact nothing to see and that instead one must keep moving, keep circulating and keep consuming. Jacques Rancière’s interaction of politics and space recalls Donna Haraway’s feminist theory of located viewing that she called “situated knowledges.”1 So what I want to attempt here is a situated critique from the no-place of the modern suburb that integrates both Rancière’s theory of the subject and Haraway’s feminist politics. For when critics have responded to Haraway’s call, they have tended to locate themselves in subcultural urban environments. The suburbs are regarded with distaste as the domain of “placelessness” that threatens to encroach on the situated urban environment. However, most Americans no longer live in cities and the politics of subcultures have become very well understood by consumer capitalism. The hegemonic residential environment is now the suburbs, that extensive and wide-ranging combination of housing, extensive service industries, health and education facilities made possible by high property prices and low-wage manual and service labor. Let’s acknowledge at once that this is a contestation of America from within, and that other very different accounts have and will be written from other places. But it seems to me important to look at the American suburb because of its extraordinary peculiarity and specificity that is predicated by American mass culture as “normality.” From this “normal” viewpoint, others can be seen as “pathological,” as in George W. Bush’s repeated assertion that Saddam Hussein is a “madman.” While reports and media from overseas are part of American everyday life, as I shall show, I cannot recreate the situated experience of watching the war in London, Delhi or Tokyo. Arundhati Roy has written about the war from India, John Docker has written from Australia, Tariq Ali from Britain and so on. Globalization creates a second “birth of the reader,” to appropriate Roland Barthes’ old phrase, in that it is the reader/viewer of these differing and disparate texts and images who occupies the position of judgment.

The American suburbs will not stand revealed at the end of this analysis as the locale of a hitherto unexpected resistance to global capitalism. After all, this is not a subculture so much as it is the majority version of American everyday life. It is the enactment of Rancière’s vision of contemporary space as being the space of circulation, where there is nothing to see. In the shopping and commuter-oriented suburbs, circulation is all. The question is, as Rancière suggests, whether this space of circulation can also be made the space for the emergence of a political and visual subject. To do so, we will have to understand the circulation anxiety of (sub)urban life. The modern suburb is not simply an absence – whether of culture, subculture or intelligence – but an intersection of signs that implicate others, in very much the way that is usually associated with urban life. That “poetics of implication,” as Robert Blair St. George has called it, that texture of suburban living, is as old as white settlement, which is to say, not very old. St. George, a folklorist working on early New England, argues that: “Poetics of implication introduces a loose, open-ended structure of feeling that works through indirection and intertextuality to create a dynamic center for political play.”2 Although St. George was writing about colonial culture, his interaction of Raymond Williams’ structure of feeling, with poststructuralist analysis, and the richly intersected notion of homo ludens – the person who plays – applies very well to our newly colonial suburbia. I would add to his poetics a politics that aspire to be at once personal, local and global in the manner suggested by Haraway. What the Situationists once called “the colonization of everyday life” entails this politics and poetics of implication and intersection. St. George argues that the poetics of implication can be effectively traced through performance and place, both of course key terms in cultural studies. My intention is to supplement that work by bringing it to bear on the unfamiliar territory of the American suburb and by considering the exigencies of the present as newly distinct from the postmodern moment in which feminism and cultural studies developed these ideas.

In the case of visual culture, the poetics of implication are one fruitful means of approaching what I will call vernacular watching.3 Based on work in feminist media studies and cultural studies, vernacular watching refers to the divergent and diverse act of looking in everyday life by which individuals become situated as visual subjects. Watching, as I mentioned earlier on, is the wide variety of things we do and places we are when we watch television. At the same time, vernacular watching tends to emphasize those moments of drift in which the attention is not fully engaged in gazing at visual media. To this end, it is intrigued by channel surfing rather than appointment television, web-surfing at work, or, to borrow a term from Anna McCarthy, the encounter with ambient media (media out of their “proper” place, such as art outside the gallery or television outside the home). 4 Vernacular watching is perhaps epitomized by the looking that is done while waiting, whether in a formal waiting room, in a car, or for some appointment. Waiting engenders boredom and distraction, the marks of a certain counter to modernity as Walter Benjamin has described them. Consequently, vernacular watching takes place in the corner of one’s eye, the passing detail that catches a glance or the sideways look at a fellow waiter. This is the transient and trans-dimensional way of seeing that visual culture seeks to define, describe and deconstruct as the transverse look or glance. The transverse glance is not a gaze because it resists the imperial domain of gendered sexuality, using what Judith Halberstam has called “the transgender gaze.”5 If this seems a little utopian, let it also be said that this transverse practice is at all times at risk of being undercut by transnational capital.

The vernacular glance sideways has several components. It is the glance that we use to look at the incident which the police urge us to move on past because there is nothing to see. It has in it that averted viewing used by astronomers to detect low-light objects by avoiding the central cones of the eye. Cultural averted viewing is done so as to better detect the faint emissions of that which is hard to see in the glare of the contemporary spectacle. Averted vision does not direct the gaze at an object but it does direct the attention. In this way, a vernacular glance sideways is a conscious effort of perceptual manipulation as well as the chance encounter in the corner of one’s eye. There are two consequences of this manipulated attention. First, it makes the watcher highly conscious of the act of watching, open to the fear of detection. Second, by diverting attention away from what is apparently in front of the viewer, it challenges the “attention economy” in which value is created by attracting our attention.6 It is with this peripheral vision that one both maintains a covert look at someone or something and becomes aware that one is being looked at, whether with desire, sexual or racial surveillance, or by another bored person waiting. It is therefore inherently complicated rather than being a simple “progressive” response to reactionary societal surveillance as manifested by the closed-circuit television camera (see Section 3). It has elements of what the African American artist Kara Walker calls the “sidelong glance.” Walker’s sidelong glance evokes the content of her dramatic cut-outs that depict the violent, bodily, and sexual dimensions to slavery that exist in the margins of the religiously inflected slave narratives. She herself asserts that this art is designed to provoke a different kind of viewing from her audience: “I really wanted to find a way to make work that could lure viewers out of themselves and into this fantasy.”7 At the same time, the sidelong glance recalls the averted glance of the subaltern, the enslaved and the colonized in historical experience. So rather than separate ways of seeing into media-specific theories of spectatorship, whether for art, film, or television, I want to consider watching as the multi-media site-specific performance of everyday life. Here I am adapting St. George’s vocabulary of performance and place to that of avant-garde art in the manner of the Situationists in order to suggest that there is no unmediated visual interface with the world.

What is seen becomes interesting when it is seen at a particular time in a given place. Cultural geographers have been working for two decades to shift our understanding of place as being the intersection of physical space with cultural discourse and power. For example, Allen R. Pred, cited by St. George, urges us to think of place as “an appropriation and transformation of space and nature that is inseparable from the reproduction and transformation of society in time and space.”8 The suburb, in this view, radically tries to prevent the formation of place by displacing time and space from modernist concepts of transformation and progress into timeless fantasies of utopia. As such it is the most advanced form of the spatialized politics described by Rancière. As suburbanites keep moving, insistently told that there is nothing to see, only shopping to do, they are describing with these patterns of movement what Marx once called “the soul of the commodity.” Time in the suburbs has lost the urgency of progressive modernity and has returned to a medieval sense of the seasons, only here the seasons are replaced by holidays. The year is marked by the transition from one holiday to the next, with decorations and merchandising for the next holiday appearing as soon as one is over. Education at elementary schools follows the same pattern so that autumn leaf projects are followed by Thanksgiving studies of Native Americans. The circuit is given coherence, a end that is also a beginning, by “The Holidays.” By this expression is meant the blend of Christmas, Hannukah, Kwanzaa, New Year’s Eve and all such other winter solstice events into a mass frenzy of consumption. As The Holidays end the year begins and the suburbs ready themselves for Valentine’s Day, only six short weeks away. In this paradise neither lost nor regained but endlessly deferred, there are other implications. In this section, I will consider my own place and sites of watching, and move on to think about what was seen from those locations during the war in the next section. Rather than look to high art, whether as film or the visual arts, for the site of mediating the war, I shall consider vernacular watching in its now hegemonic sites in suburban America: the hyperhouse, the superstore and the Sports Utility Vehicle (SUV).

Suburban Babylon

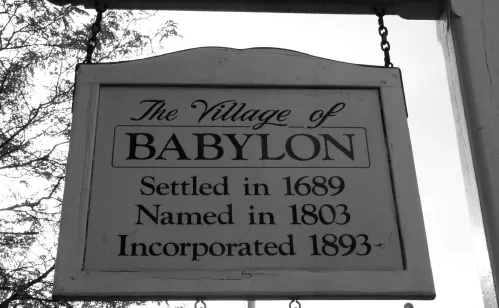

So to begin with Long Island, New York, where I live and where I watched the war, and where there is a Babylon of our own. The abject other to the metropolis of New York, Long Island has been described by Lou Reed, a native, as the “armpit of the universe.” It is Long Island’s very lack of appeal to East Village media and cultural sophisticates that makes it interesting as a site of vernacular watching. Long Island is, as the name suggests, a long, thin island adjacent to the island of Manhattan. One hundred and ten miles long and only fourteen miles wide, it is the site of two of the boroughs of New York City, Queens and Brooklyn. Further east are commuter suburbs, ex-urbs that seem to be suburbs but do not move in the orbit of New York; a little remaining farmland, mostly for wine; and the gilded estates of the Hamptons. Long Island is also home to the town of Babylon, incorporated in the late nineteenth century as part of one of the original eight towns on the island created by the British colonists. Settled since the mid-seventeenth century, Babylon took its name from an estate named New Babylon, founded in 1803 by one Nathaniel Conklin, made wealthy by the paper mill established by his father.9 This unlikely name for Protestant New England arose when Conklin’s mother sniffed at his choice of location, calling it “another Babylon.” The name has curious echoes, both of the Situationist project New Babylon, and the Orientalist assumption that Baghdad was New Babylon. On Long Island, Babylon was a stop on the stagecoach out of New York City and home to the notorious American Hotel. On June 1, 1843, Isabella van Wagenen decided to leave New York City and change her name to boot. When she arrived in Long Island as Sojourner Truth, she headed for Huntington.10 Along the way in a curious incident, she was put up for the night by a strange couple who insisted on taking her to a ball, with drinking and dancing to the small hours.11 This place may not have actually been Babylon – though it must have been close – but for Truth, now committed to the Millerite Evangelicals, it was certainly Babylon in the metaphorical sense. One figure who definitely did visit the new Babylon was Oscar Wilde, who gave a lecture there during his American tour of 1882. It is a matter of debate as to whether his thoughts on “The House Beautiful” properly took root in Long Island’s sandy soil.

Figure 1.1 The village of Babylon, Long Island

Despite this history, Long Island is a place that urban sophisticates and decadents have long sought to escape in keeping with the modern American drama of urban relocation and self-discovery, epitomized in Jack Kerouac’s 1957 book On the Road and in films like Easy Rider (1969). For many others, green suburbs with decent schools and low crime rates form an attractive “bourgeois utopia,” to quote the title of the 1989 pioneering study of suburbs by Robert Fishman. Yet this utopia is thin on the ground, as countless films, novels and photographs have pointed out. The difference is now that the city no longer provides an automatic refuge from suburban anomie. The keynote of contemporary (white) middle-class life in towns, cities and suburbs is circulation anxiety, stemming from a worry about what that “nothing to see,” which Rancière’s police keep us away from, really is. Knowing very well that there is in fact something to see, we move on nonetheless, worrying about what it was that we couldn’t see and obeying the command out of a general sense of foreboding. The events of 9-11 were, in this sense, the culmination of a long habitation with fear, registered in terms of race and international politics, formerly communism, now terrorism. These motivated anxieties register as alienation, neurosis and above all as the desire to consume. Consumption is here, as befits a settler society, the act of generating (white) social space, a Babylon of the domestic, featuring extravagant Babylonian spaces in oversized cars and oversized houses sheltering oversized TVs. Here I think of the opening sequence of the hit TV series The Sopranos. We see Tony, a middle-aged man with a cigar, driving his SUV along the postindustrial wilderness of the New Jersey Turnpike, past the relics of first and second generation immigration like the pork store, the pizza palace and the modest one-family home, to arrive at his hyperhouse, the scene of the internal drama that will then be analyzed by the psychoanalyst Doctor Melfi. To retreat from this world, Tony goes to watch the History Channel on TV, the all-Hitler-all-the-time history-as-entertainment channel. In this televisual retreat, Tony finds watching documentaries about the Second World War to be a place where good and evil are clearly defined and distinguished, literally in black and white, unlike the chaos of his own life. The Sopranos rewrites the public sphere as the private world of cars, houses, and family, and makes disfunction into narrative.

Figure 1.2 An 1806 house ...