eBook - ePub

Urban Nightscapes

Youth Cultures, Pleasure Spaces and Corporate Power

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Nightscapes

Youth Cultures, Pleasure Spaces and Corporate Power

About this book

In many western cities, urban nightlife is experiencing a 'McDonaldisation', where big branded names are taking over large parts of downtown areas, leaving consumers with an increasingly standardised experience.

This book takes a new look at this rapidly changing aspect of urban life, examining the relationships between young adults, nightlife and city spaces. It focuses on what the authors call 'urban nightscapes' - both mainstream and alternative youthful cultural activities in bars, pubs, night-clubs and music venues, which occur against a backdrop of increasing corporate influence in the night-time economy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Nightscapes by Paul Chatterton,Robert Hollands in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Making Urban Nightscapes

This book is about the making and re-making of urban nightlife. While a night out is a common and widespread experience, many of us do not spend much time thinking about what exactly goes into its making, which is not surprising as most of the time we are too busy enjoying ourselves. For example, rarely do we pose questions such as: who owns and profits from the nightlife venues we socialise in? Who develops, designs and promotes nights out and for which groups? What laws and legislations govern nightlife and how it is policed? What implicit and explicit codes structure a night out, which people go to which venues and why, and what do young people actually think about their nightlife experiences? What follows in this book is an attempt to unpack these related sets of issues.

What this book is not is a celebration of the diversity and the countless experiences which a night out can offer. Such a venture is clearly another project in itself. This is also not another book solely about clubbing or rave culture, or indeed drug and Ecstasy cultures (of which there have been numerous examples: see, Malbon, 1999; Saunders, 1995; Redhead et al., 1997), but more broadly ‘urban nightscapes’, which entails a variety of youth cultural spaces and groups, including those who are excluded from, or challenge, what’s on offer downtown at night. Instead, in what follows we pursue a more political-economy perspective of a night out, which not only looks at consumer experiences and draws upon our real experiences with young people during a night out, but also explores issues of production and regulation. Hence, our work takes a critical look at the role of the entrepreneurial local state, the various effects of corporate capital, and the increasing uniformity and standardisation of many modern-day consumer practices. To give the reader some idea of what to expect in the following pages, our main concern relates to the growing dominance of large corporate operators and their nightlife brands, and what this means for the future character and liveability of urban areas.

We start this book within a context of change and transformation. Social and economic restructuring over the last three decades has resulted in the development of a new urban ‘brand’ which has reshaped many parts of city landscapes into corporate entertainment and leisure hubs (Gottdiener, 2001; Hannigan, 1998). While urban areas have always been sites of pleasure-seeking, a central focus of recent rebranding has been the promotion of the night-time economy, much of which is characterised by the ritual descent of young adults into city-centre bars, pubs and clubs, especially during the weekend (Hollands, 1995; Thornton, 1995; Chan, 1999; Andersson, 2002). One stark example which provides a glimpse into the widespread nature of the growth of night-time entertainment, and gives us a way into thinking about the making, remaking and unmaking of urban nightscapes, comes from Barcelona in the Catalunya region of Spain, and more specifically the Port Vell area on the city’s water-front. This area has been unrecognisably transformed since the mid 1990s, from a decaying old dock area into one of the city’s foremost and most fashionable party zones. The main quay is dominated by the Maremagnum complex, an entertainment and shopping area opened in 1995 containing around fifty shops, twenty-five restaurants and dozens of bars and clubs (see Plate 1.1). The 2001 Time Out guide to Barcelona states: ‘Maremagnum gleams temptingly in the middle of the Port Vell and draws in huge crowds both night and day.’

Plate 1.1 Maremagnum Entertainment Complex; Port Vell, Barcelona, Spain, 2002

An initial and indeed understandable response is to applaud such a development as a positive example of ‘urban cultural revival’ (Landry, 2000; Comedia and Demos 1997). Indeed, the night-time economy in many cities has now become an accepted part of wider urban renewal strategies and is seen as a significant source of income, employment and civic ‘image-building’ (Chatterton and Hollands, 2001, 2002). However, there is another largely untold story here. Port Vell, for example, the once-glistening jewel in the gentrified regeneration of Barcelona’s waterfront has recently lost some of its lustre. The reality by 2002 was that the city’s wealthier population, who once danced and drank here with style, have moved on to the latest nightlife venues elsewhere. As a result, Maremagnum has become a more middle-ground ‘mainstream’ nightlife space for young, often under-age, tourists and the city’s immigrant and working-class communities. After forty incidents involving the police at the leisure complex between 2000 and 2002, complete with security guards armed with batons, the problem finally came to a head. In January 2002, it was alleged that four door staff from Bar Caipirinha in Maremagnum beat and then threw a young Ecuadorian immigrant, Wilson Pacheco, into the sea when he became aggressive after he was denied entry to the bar. Pacheco drowned, creating a media frenzy calling for a new set of nightlife regulations, and Bar Caipirinha was closed. Subsequently, the Catalan Interior Ministry, along with the Barcelona city government and the port authority, developed a plan to restrict late-night bar and alcohol-led activity in the area and promote a greater diversity of more cultural and family-oriented activities.1

Although only a single example, what exactly does this ‘other’ story reveal about the making and remaking of urban nightscapes generally? First, it demonstrates that while there is a growing popularity and domination of large-scale, glossy corporate nightlife developments in many cities around the world, they often contain their own set of contradictions. Constant attempts to upgrade and gentrify urban waterfronts and central areas, which include nightlife facilities, invariably result in a tail-chasing game of ‘cool-hunting’ (Klein, 2000), as young professionals go in search of the latest cool, chic, fashionable bar or club, leaving yesterday’s stylish haunt in their wake. Indeed, much of the new nightlife economy is all about being ‘cool’. In their attempt to define this rather tricky term, Pountain and Robins (2000) point out that coolness, as a consumption strategy, is largely an individual identity strategy rather than a collective political response. As the authors suggest, ‘no-one wants to be good any more, they want to be Cool’ (ibid.: 10). Yet, more importantly for this book, coolness has also become a vehicle for big business, the media and advertisers to push their way further into the wallets of young consumers.

Second, while such upgrading initially appears to be enforced through pricing and various stylistic codes, it often requires more ‘direct’ and violent forms of regulation (i.e. bouncers, security staff; see Hobbs et al., 2000) which, as the Maremagnum example shows, can quickly spiral out of control. Finally, attempts to gentrify leisure and the night-time economy in the city have resulted in various nightlife consumption groups jockeying for position and territory, leading to a socially segregated, conflictual and increasingly polarised use of space (Hollands, 2002).

The above example from Barcelona, then, reflects some of the main concerns of Urban Nightscapes. Our focus is ‘urban’—and in particular downtown—areas, which continue to represent the most visible manifestation of these trends, especially in Europe. However, we are cognisant that our discussion reflects broader social and cultural changes rather than mere ‘city-based’ phenomena (see Gottdiener, 2001). In this sense, many of the processes we emphasise, including economic concentration, corporatisation, branding and theming, segmentation of consumer markets and pandering to middle-class tastes, are occurring across central, suburban and complex polycentric city-regions (Soja, 2000) across the western world, and clearly here North America is leading the way. This is not to say that there are not important variations in nightlife cultures between countries and cities and that wider processes do not work themselves out at different rates in specific local conditions. For example, there are clear differences in nightlife infrastructures between larger global cities, established metropolitan centres and smaller cities. However, the phenomena we are studying are increasingly global, or at least western, in their orientation, and hence it is possible to generalise findings to some degree, as the night-time economies of many post-industrial countries continue to converge and follow similar trends.

Our second focus is on the term ‘nightscapes’, which refers specifically to young adults’ varied nightlife activities in licensed premises such as bars, pubs, nightclubs and music venues, as well as the streets and spaces in-between. We recognise that other activities such as cinema, theatre, restaurants, casinos, cafés and sporting events also combine to make up these nightscapes, but these are not our concern here as they are not primarily the preserve of young people in cities. 2 Our use of the term ‘nightscapes’ also refers to issues raised by Zukin (1992) about the aestheticisation and commodification of urban landscapes, but also tothe increased use of the city as a place of consumption, play and hedonism in the evening (Featherstone, 1991).

The Framework

Studying nightscapes entails unravelling certain inherent difficulties, contradictions and dichotomies involved in the actual ‘experience’ of nightlife. We are acutely aware that framing it through academic discourse and theoretical concepts erodes much of the fluidity, excitement and sociability of a night out. It is quite impossible to capture what the city is about at night within the stiff pages of an academic text. In fact, any attempt to represent nightlife will automatically make certain groups and actions more visible than others. The city, especially at night, contains many contradictory elements that cannot always be resolved, understood or related. Nightlife is simultaneously conflictual and transgressive, at the same time as being segregated, commodified and sanitised. It also has emotional (enhanced through alcohol, drugs, dance, sex, encounter) and rational elements (planning, surveillance and policing), which are not always easy to understand and reconcile. Nevertheless, it is worth highlighting, to quote Thornton (1995:91), that ‘the seemingly chaotic paths along which people move through the city are really remarkably routine’.

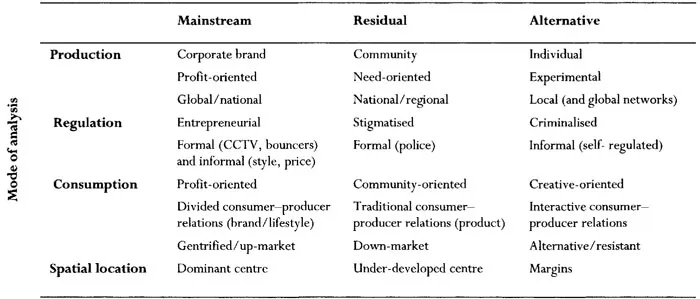

Our perspective is to stress the active making and remaking of urban nightscapes, an approach which is sensitive to processes as well as possibilities. As such, the book operates on two levels (see Table 1.1). First, we present an understanding of nightscapes through an integrated ‘circuit of culture’ which comprise the three processes of production, regulation and consumption (Du Gay, 1997). By this we mean that, to fully understand an area of activity such as nightlife, it is imperative to simultaneously explore who and what is involved in producing nightlife spaces (i.e. designing, marketing, selling, property markets, corporate strategies, etc.), who and what is involved in regulating them (i.e. laws and legislations, surveillance, entrance requirements, codes of conduct), and who and what is involved in consuming them (i.e. lived experience, perceptions, stereotypes, etc.). Hence, while nightlife venues are clearly commercially manufactured by a range of multinational, national, regional and local operators, and regulated by various legislative frameworks and formal and informal surveillance mechanisms, it is also necessary to explore the lived consumer experience and the role young adults play in shaping such spaces.

Table 1.1 Mapping out urban nightscapes

Source: Chatterton and Hollands, 2002

Second, urban nightscapes can be understood as a mixture of mainstream, residual and alternative nightlife spaces. Mainstream spaces are the well-recognised commercially provided bars, pubs and nightclubs that exist in most large urban centres. While there are a range of venue types here, the unifying feature of the mainstream is that it is driven by commercial gain and the profitmotive, rather than the other concerns such as access, equality or creativity. The mainstream is also characterised by ownership by large national and international corporate players who are increasingly using strategies like branding and theming to target and segment certain cash-rich groups such as professionals and service sector workers (including professional women and the gentrifying gay population) and higher education students. These spaces cater for much of the hedonistic rituals and raucous behaviour one normally associates with a night out. Residual community spaces such as traditional pubs, ale-houses and saloons, as well as the purview of the street, which were a common feature of most industrial city centres have been left to decline or are disappearing altogether, due to the changing priorities of nightlife operators and consumer tastes. Finally, there is a range of independently run and alternative nightlife spaces which cater for more specific youth cultures, identities and tastes, some of which are self-organised, such as free parties, unofficial raves and squatted social centres. Clearly, spaces such as the mainstream, the residual and the alternative and resistant margins are constantly shifting entities, with rather nebulous boundaries. Today’s fringe cultures become tomorrow’s mainstream fashions. Hence, we have tried to avoid over-literal interpretations which regard the mainstream as mere commercial blandness while the underground is teeming with resistance and creativity. Instead, we have focused upon how different spaces and boundaries are made and remade, regulated and experienced.

The central argument of Urban Nightscapes is that urban nightlife is increasingly characterised by dominant regimes of: mainstream production, through the corporatisation of ownership via processes of branding and theming (Klein, 2000; Gottdiener, 2001); regulation, through practices which increasingly aid capital accumulation and urban image-building (Zukin, 1995; Harvey, 1989b) yet increase surveillance (Davis, 1992); and consumption, through new forms of segmented nightlife activity driven by processes of gentrification and the adoption of ‘up-market’ lifestyle identities among groups of young adults (Butler, 1997; Wynne and O’Connor, 1998; Savage and Butler, 1995). In this sense, although many city centres have achieved a ‘cool’ status through branded and upgraded nightlife, they are also increasingly becoming more exclusive, segmented and conflictual arenas (Smith, 1996; Sibley, 1995). And while we stress that new opportunities have opened up, especially for young women (McRobbie, 2000), ethnic cultures and music (Forman, 2002) students (Chatterton, 1999), and gay nightlife in particular (Knopp, 1992), these have often been sanitised and commercially incorporated into the mainstream. Moreover, historic, residual and alternative forms of nightlife are increasingly marginalised to the geographic periphery of the urban core, over-regulated until they simply disappear, transformed by the changing corporate priorities of their owners, or are bought out under the weight of urban renewal and gentrified leisure.

Our concern, then, is how to make sense of production, regulation and consumption patterns within urban nightlife infrastructures, with a focus on young adults’ experience and use of particular spaces. Our emphasis on processes and the ‘making’ of nightlife circumvents, we hope, some of the rather unhelpful dichotomies used in understanding youth lifestyles, such as culturalism versus structuralism, objective versus subjective and material versus symbolic constructions of society (see Miles, 2000 for a discussion of some of these approaches). As such, throughout the book we use examples of how young people actively talk about, and make sense of, their social and spatial world and that of others in the night-time economy.

In this regard, first, it is fair to say that much youth cultural analysis has been implicitly aspatial in its orientation (for an exception, see Skelton and Valentine, 1998; Massey, 1998). Therefore, we seek to locate nightlife provision and youth experiences in a spatial context, both in our use of notions like mainstream, alternative and residual spaces, and also in terms of different national and local conditions. Second, with regard to understanding the relationship between ‘circuits of culture’, there are many ways to unpack consumer experiences, including nightlife. ‘Horizontal’ readings explore the relations and meanings circulated between consumers, while Vertical’ readings consider consumers as part of a commodity chain including production as well as consumption (Williams et al., 2001). While we attempt to utilise both of these approaches, we give particular weight to the relationship between the production and regulation of nightlife, and its consumption by young adults. In this sense, we adopt a spatialised ‘political economy’ of youth cultural activity in the night-time economy, combined with a neo-gramscian perspective which stresses the interplay of dominant, residual and emergent tendencies (Williams, 1977). Political economy has been sorely neglected within the study of popular and youth culture generally (although see Fine and Leopold, 1993; Hollands, 1998), and traditionally much youth cultural analysis has focused on cultural resistance (Hall and Jefferson, 1976; Willis, 1990), postmodern hybrids (Muggleton, 1998) and the active making of lifestyles (Miles, 2000), without exploring this wider context of the changing role of the state and corporate strategies.

So, while we are sympathetic to elements of an ‘agency-based’ or ‘experiential’ approach (see Malbon, 1999), we also feel that a preoccupation solely with cultural creativity underestimates the material constraints in which consumers operate, as well as ignoring ongoing fundamental inequalities within the youth population. Clearly, young adults are actively involved in meaning-making in the night-time economy (see Malbon, 1999); however, at the same time many nightlife premises have become, to paraphrase Le Corbusier, ‘gentrified machines for drinking in’. Similarly, it is important to stress the endurance of significant consumption divides within youth populations (Furlong and Cartmel, 1997)—between, for example, unemployed young people or those dependent on unstable employment, university students and those in high-level training, and young professionals in stable, well-paid and mobile employment—as well as to understand how social divisions have become more complex today. Our approach, then, is that wider processes of capital accumulation and restructuring, especially through the globalisation and corporatisation of the cultural industries (Klein, 2000; Monbiot, 2000), enduring social inequalities, and the changing role of the state, all are extremely influential in shaping modern-day nightlife experiences. Hence, to borrow from Marx: ‘Young adults make their own nightlife, but not under conditions of their own choosing.’

Key Concep...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: making urban nightscapes

- Part I Understanding nightlife processes and spaces: producing, regulating and consuming urban nightscapes

- Part II Urban nightlife stories: experiencing mainstream, residual and alternative spaces

- Notes

- References

- Index