1

RE-CONCEPTUALISING FAMILIES

Eileen Drew

Introduction

This chapter charts the demographic changes characterising the last three decades, which have resulted in a diversity of family forms. It marks the magnitude of some of these changes, the exceptions to general patterns and how these may be combined to offer a new perspective on how we might view ‘families’ and ‘households’ in Europe. Macintyre states:

Though sex, marriage, and reproduction may be linked empirically in a particular society and its dominant ideology We cannot assume a priori that people have babies because they are married, or marry in order to have babies; nor that people have babies because they have had sex, or that they have sex to produce babies.

(Macintyre 1991:3)

The chapter provides a backdrop to the theme of Part I, ‘Re-conceptualising Families’, illustrating how the concept of family differs between member states for historical, religious and developmental reasons.

Demographic trends

Demographically, Europe has experienced a reduction in infant mortality, increasing life expectancy and decreasing fertility. Not only have the number of births (particularly third and subsequent births) been reduced, there has been a postponement of first and often subsequent births and a rise in childlessness. In tandem with these trends, there has been an alteration in the choices available to individuals and couples, exemplified by the lower marriage rates, higher levels of cohabitation, increased divorce and re-marriage rates and births outside marriage. There is no longer adherence to permanent monogamous family units as the basis for family life.

Life expectancy and ageing

General mortality rates declined steadily between 1960 and the 1990s leading to improvements in life expectancy which have continued in most countries of the European Union. Table 1.1 sets out the life expectancy1 at birth for women and men in the European Union and how these have altered since 1960.

By 1994 women’s life expectancy was 80 years or over in France, Sweden, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Greece and Belgium. Male life expectancy was highest in Sweden, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK, where it exceeded 74 years. Since 1960, the former north-south differences in life expectancy have largely disappeared or reversed. Women’s life expectancy continues to exceed that of their male counterparts and in some countries the gap is widening. In the early 1960s, female life expectancy exceeded the male rate by an average of 5.2 years and this rose to 6.5 years in 1992. The differential varies country by country. France has the largest male—female life expectancy gap of 8.1 years.

Declining fertility rates and higher life expectancies contribute to an altered age structure, resulting in an ‘ageing of the population’ throughout Europe whereby an increasing proportion of the population consists of people over 75 years, a trend which is set to continue into the next century Table 1.2 sets out the proportion of the population which is/will be aged 75 years and over. In 1960, only 3.6 per cent of the EU’s population had reached 75 years, the level rose to 6.3 per cent in 1990 and will be nearly 8 per cent in the year 2020. This represents a major shift in the population structure compared with only a century ago.

Table 1.1 Life expectancy at birth in the European Union (14) 1960–94

Table 1.2 Percentage of the population aged 75 years and over in 1960, 1990 and 2020

Combined with the decline in marriage and increased divorce, it is likely that an increasing number of elderly people will live alone and to varying degrees this could place a burden of responsibility for caring on offspring, other family members and/or the state.

Fertility rates

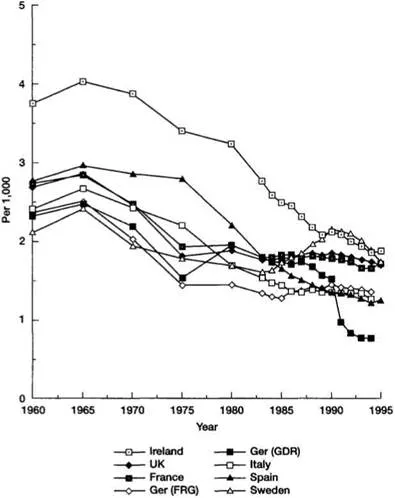

The trend towards fertility decline has been traced back in some parts of Europe to the end of the eighteenth century. With the exception of the period 1945 to 1965, which witnessed a rapid increase in births, the general trend has been one of steady decline during this century. Figure 1.1 shows the rapid rate of decline in fertility since 1960 throughout Europe, and the considerable variations in the geographical patterns of fertility decline.

It is in Germany, particularly the former GDR2 and southern EU countries that fertility decline is most dramatic. In 1994/95, apart from Germany’s GDR, Spain had the lowest total fertility rate in Europe (1.24), followed by Italy (1.26), Germany (1.35) and Greece (1.35) (Table 1.3). In contrast, it is in the northern and western EU states that higher than average fertility is recorded in recent years. Based on recent Eurostat forecasts of total fertility up to the year 2020: Sweden and the UK are expected to maintain a fertility rate of 1.90; followed by Denmark, the Netherlands and France with a fertility rate of 1.80, compared with a rate in Ireland of 1.50 and Spain of 1.13 (Eurostat 1995a). Fertility in Sweden never fell to very low levels (the lowest was 1.56 in 1983) and the social policies pursued by the Swedish government have (somewhat uniquely) ‘tried to facilitate women’s entry into the labour market and their continued attachment to it at minimal cost to childbearing and childrearing’ (Hoem 1990:740).

Figure 1.1 Total fertility rate in selected European Union countries. Source: Eurostat (1996a).

The link between fertility and social policy intervention is extremely important. One of the themes for further and urgent research is whether rapidly declining levels of fertility (as experienced in Spain and Italy) represent freedom of choice by women, or a pragmatic response to the lack of social supports (separate taxation, childcare, flexible work practices, parental leave). The Swedish example represents an interesting alternative model to those states experiencing rapidly declining fertility rates. Norway’s response to the prospect of population decline from 4 million to 3 million by the year 2010 was to appoint a Population Committee in 1981. The Committee concluded that a stabilisation of fertility, near to replacement level, should be sought and recommended radical improvement in the living conditions of families with children. It sought an extension of paid maternity leave from 18 weeks to one year; an adequate supply of kindergartens; public care arrangements for children entering school and improved living standards for families with small children through public transfers (Jensen 1989). The author notes that there has been little sign of radical action following these proposals.

Table 1.3 Trends in total fertility rate3 of the European Union (15) 1960–94/5

Hall has concluded that given the availability of contraceptive technology, higher levels of education, rising living standards and how these impact on women’s lives in terms of labour force participation, ‘it seems unlikely that fertility will rise much, unless a wide range of public policy measures is introduced to help parents combine parenthood with paid work. Even then it is unlikely that fertility would rise significantly’ (1993:7).

Maternity—to be or not to be a mother

Folbre (1994:111) has contested that fertility decline is not due simply to an aggregation of individual choices, to conceive or not, but is a ‘circular process of struggle over the distribution of the costs of children [which] accompanies the technological changes associated with fertility decline’. Throughout western Europe, women born after 1945 have increasingly altered their reproductive behaviour by controlling their fertility and delaying childbirth. Women can make more deliberate decisions about whether to have children; when to commence, space and complete family formation. Part of this exercise of choice relates to the number of children, whether they are born within marriage or a stable union. The overall rise in childlessness suggests that women now have the means to make real choices rather than to accept some form of reproductive imperative, should they wish to be sexually active. Childlessness in Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK had been 10 per cent for women born in 1945, rising to 18 per cent for those born in 1955 (Hall 1993).

A key indicator of preference being exercised by women is in relation to the age of mothers when their first child is born. In the 1960s there was a pattern of women having their first child at an earlier age of 26 to 27 years, coinciding with the ‘baby boom’. During the 1970s this trend reversed in all countries so that by 1993 the mean age of first time mothers was 29 years (Eurostat 1995a).

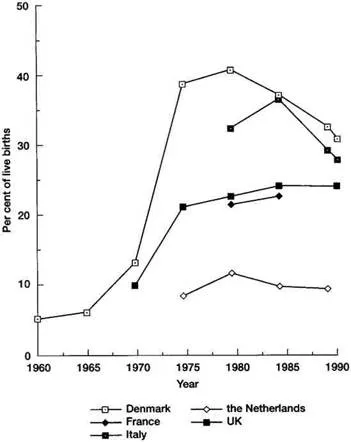

Another trend which has manifested itself to varying degrees in Europe is in the rate of legal abortions.Figure 1.2 shows that Denmark’s abortion rate4 was 5 per cent in 1960. Along with other countries (including the UK and Italy) freer access to abortion in Denmark was introduced in 1973 by legislation, following which the abortion rate peaked at 41 per cent in 1980, when the fertility rate was very low. This rate was almost matched by Italy in 1980, following legalisation. During the 1980s there has been a decline in the abortion rate in all the countries for which data on legal abortions are available (Drew 1995a).

Further evidence of women’s exercise of choice is in relation to the marked and rapid decline in third and subsequent births. These had formed one-third of births in the European Union countries in the mid-1960s but fell to just one-sixth of births in the 1990s. Higher levels of third or higher births are still found in Ireland (35 per cent), Finland (26 per cent), the UK (24 per cent), Sweden (24 per cent) and France 22 per cent) compared with lower rates in Denmark and Greece (17 per cent) and Italy and Portugal (15 per cent) (Eurostat 1995a).

Marriage rate

According to Boh (1989:276):

changes in marriages in European societies were first marked by a dramatic swing to higher incidence of marriage and to falling age at marriage, to be followed by an inverse trend characterised by a decrease in marriage rates and an increase in the age at marriage, a growing number of divorces and cohabitations.

The total number of marriages peaked in 1970 with 2,625,503 in the EU (15) and fell to 1,939,279 in 1994. All EU states experienced a decline in marriage rates from 1970. Within the EU, the highest marriage rates in 1994 were in Denmark (6.8 per 1,000) and Portugal (6.7 per 1,000), followed by the UK (Eurostat 1996a).

Figure 1.2 Legal abortions in selected European Union countries. Source: Eurostat (1993a).

Alongside this trend and the tendency for women to postpone the birth of a first child, the average age at marriage has increased for women by between two and three years since 1970 in many countries. Denmark switched from having the youngest mean age for women at first marriage of 22.8 years in 1960 to the oldest, 28.9 years in 1994. The mean age at first marriage of women in the European Union was 24.1 in 1960, 23.2 in 1970 and 26.1 in 1993. Among men there has been a similar shift towards marrying later with a mean of 26.7 in 1960, 25.9 in 1970 and 28.5 in 1993 (Eurostat 1996a).

Cohabitation

The postponement of marriage is related to the increased popularity of cohabitation which often precedes and in some cases replaces marriage. As Hall (1993:8) states ‘no longer is marriage seen as the only organising principle for relationships’. Boh (1989:277) points out that in Europe cohabitation was not unusual in rural regions. However it now represents a newer trend whereby legal marriage has ‘given way to a variety of optional non-traditional forms of “living together’”. This pattern was more frequent in the Nordic countries and has also increased in the Netherlands, France and the UK, but is still less frequent in Belgium and Italy (Boh, 1989). Boh (1989:279) also claims that cohabital unions ‘have everywhere functioned more as a trial marriage than as a more permanent alternative to formal marriage’, since ‘most cohabiting couples marry once they have children’.

Although EU data on cohabitation are not readily available, figures for Ireland suggest that fewer women were in non-marital unions compared with the Nordic countries. Cohabiting couples in Ireland accounted for 3.9 per cent of all family units in 1996 (Central Statistics Office 1997). Given the quite steady rise in births outside marriage in Ireland since 1980, it is likely that the situation in relatively ‘traditional’ and Catholic societies such as Ireland and Italy are moving towards the Nordic and European pattern of cohabiting.

It is difficult to gauge the rate of long-term consensual unions which do not result in marriage. However there is evidence of a growing proportion of older age cohorts among the ‘never married’ in some countries. Although fewer than 9 per cent of women aged 35–39 in Denmark had never married in 1984, the proportion for men was 18 per cent. It is in Sweden that there has been a steady rise. In 1970, only 11.6 per cent of women aged 30–34 years had never married, a level which increased to 36 per cent in 1984. There was a similar rise among 35–39-year-old women and the proportions for ‘never married’ men in these age cohorts was even higher (Hoffmann-Nowotny and Fux 1991). In Ireland, 43 per cent of women and 55 per cent of men in cohabiting unions were aged 30 years or more, confirming that cohabitation is not just a precursor to marriage but a more permanent form of union (Central Statistics Office 1997).

One further pattern which represents another alternative to marriage and cohabitation is of ‘living apart together’ in separate households. Hoffmann-Nowotny and Fux (1991:51) have identified this option which accords with ‘societal ideologies of individualism and equality, and becomes structurally more feasible with an increasing material independence of women’.

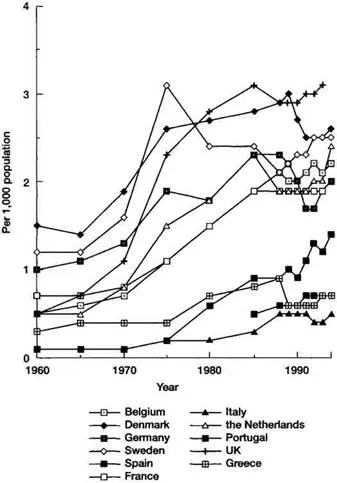

Divorce rate

Since 1960 there has been a rise in European divorce rates5 (Figure 1.3) from 0.5 per 1,000 to 1.7 per 1,000 in 1993 (Eurostat 1996a). At current rates, it is estimated that 40 per cent of marriages in the UK will end in divorce (Hall, 1993). There has been some stabilisation of divorce rates in the later 1980s but this may be due to a rise in cohabitation and lower rates of re-marriage among divorced people. Within the EU (15) divorce rates were higher in the UK (3.1), Denmark, Sweden and Finland (2.5) than in Greece (0.7), Spain (0.7) and Italy (0.5) in 1993 (Eurostat 1996a).

Part of the increase in divorces has occurred in response to a liberalisation of divorce legislation away from a system based on matrimonial offence, guilt and punishment to one based on irretrievable breakdown, mutual responsibility and need. It is also argued that the rate is high due to the democratisation of relationships and the increased independence of women. Other social factors which are commonly cited are the individualisation and privatisation of marriage, with individuals seeking higher expectations of personal happiness and self-fulfilment. These break with the traditional adherence to conformity and duty (Boh 1989). With the rise in the rate of divorces there has been a removal of the stigma attached to being divorced, particularly for women. Gittins (1993:9) posits the view that the divorced state now displaces the experience of widowhood, a much commoner event in centuries past: ‘the common-sense notion that all families in the past were much more solidaristic and stable institutions cannot be borne out—death saw to that’.

Figure 1.3Crude divorce rate in selected European Union countries. Source: Eurostat (1996a).

Another feature of the higher divorce rate is the pattern of remarriage and stepfamilies. In most countries there has been a rise in the number of marriages by divorced women and men from 1960 to 1990/1, when this increase was halted. The exceptions are in Spain, Finland and Portugal where the number of remarriages continues to rise. Remarriage by divorced persons is higher among men than women, reflecting a possibly greater reluctance among women to remarry and the higher probability that women will have responsibility for children from a previous relationship (Hoffmann-Nowotny and Fux 1991). Gittins (1993) again reminds us, by the all too common appearance of ‘wicked stepmothers’ in fairy tales, of the common practice of remarriage and children living with stepparents/ siblings throughout recorded history

Delphy (1991:46) would argue that while at an individual level a divorce signifies the end of a marriage, ‘it by no means implies the end of marriage as an institution. Divorce was not invented to destroy marriage since divorce is only necessary if marriage continues to exist.’ Commenting on the virtual monopoly women have over assuming care for children after divorce, Delphy (1991:56) places this on a continuum of women’s responsibility for children ‘which exists before the marriage, is carried on in the marriage, and continues afterwards’. For Delphy this responsibility can be defined as the exploitation of women by men and the collective exemption of men from the cost of reproduction.

...