![]()

Chapter 1

Rethinking Nostalgia

In The Mood for Love and Far From Heaven

History, memory, nostalgia

One of the most significant developments in film studies over the last fifteen years or so has been the growing preoccupation with memory and nostalgia. The recourse to history and the archive in the wake of the revision of 1970s film theory, together with the dramatic impact of global technologies on thinking about personal experience and identity, have focused attention on the dismantling of traditional power relations between producers and audiences. The authority assumed to reside in the text as the location of official meanings and ideologies has shifted to the viewer, perceived as a kind of scavenger, engaged in a process of appropriating the text and rewriting it to suit their own purposes. So-called 'dominant' ideologies, whether of patriarchy, capitalism or colonialism, have been overturned, or at least challenged, as consumers have disassembled and reassembled them, producing new configurations and interpretations that emerge from localised sites often far removed from the source texts and their producers. This has resulted in a startling proliferation of discursive intertexts and textual commentaries, whose origins and validity are not always clear, which have the potential to transform the way history is traditionally written and perceived. At the same time, the master narratives of major events focused on the activities of public figures have shifted to include the experience and perspective of the 'ordinary person'. This situation has been dramatised in films such as Forrest Gump (1994), whose use of special visual effects to place its naive, fictional hero at the centre of recorded American history has been much discussed. Television has produced series such as People's Century (1998-9), which tells the history of the twentieth century through the eyewitness accounts of ordinary folk, and dramas of reconstruction such as The Trench (2002), which invited viewers to participate in the re-enactment of traumatic battlefield experiences of the First World War.

While they emerge from very different production circumstances, these examples share a number of features. Forrest Gump foregrounds the processes of reconstruction, creating an amalgamation of past and present, documentary footage and fiction, which acknowledges the way history and myth are elided in national memory. People's Century also manipulates archive footage and contemporary interview material, but it effaces the process of fabrication, presenting both as documentary evidence and thereby authorising itself as history, albeit unofficial. While both Forrest Gump and People's Century superimpose the present on the past, The Trench goes one step further, recreating the past as theatre to be performed and re-lived in the present. This was a controversial move, provoking criticism that to submit the participants to such harrowing experiences for the purposes of media spectacle was exploitative and in poor taste. History, it seems, requires a proper distance.

One of the effects of such media experiments is to bring spectators closer to the past, to produce a kind of second-hand testimony that includes the audience as witnesses to reconstructed events. These postmodern histories, which are events in themselves, rely on empathy and identification to create memories that are not based on first-hand experiences, but which nevertheless have a powerful emotional affect. Our access to history, via memory, is by way of imaginative encounters in which viewers figure, often heroically (the Forrest Gump syndrome) and sometimes ironically (as with the theme park masquerade), as performers in a pageant. The term 'prosthetic memory' has been used to describe the process whereby reconstructions of the past produce replacement memories that simulate first-hand experience. Such enterprises lay themselves open to charges of lack of authenticity, of substituting a degraded popular version for the 'real' event, and to accusations that by presenting history as dramatic spectacle they obscure our understanding of social, political and cultural forces. The pessimistic view assumes that the images and stories of the past fed to us by the global media networks produce 'false' memories, or at least memory scenarios whose veracity, or relationship to the real, are impossible to determine. Yet, in the very act of addressing audiences as nostalgic spectators and encouraging them to become involved in re-presenting the past, the media invites exploration and interrogation of the limits of its engagement with history. Where authentic histories claim to educate us about the past itself, imposing narrative order on chaotic reality, these modern-day reconstructions tell us more about our relationship to the past, about the connections between past and present, and our affective responses. They can also inspire viewers to seek further knowledge and understanding.

There is often a sense of melancholy about critiques of media attempts to memorialise history through dramatic reconstruction. A sense of despair prevails, as though something has been lost that is now irrecoverable. What is mourned is not so much the loss of 'reality' itself - although that is certainly in element in some writing, where manipulated media images are said to take the place of actual events in the minds of spectators, completely circumscribing their understanding of what has taken place. Rather, what is assumed to be lost is an ethical dimension, in that audiences are deemed to have been duped into accepting inauthentic versions and forgetting the 'truth'. What has been lost, it seems, is the authority of history itself, and its ability to produce convincing and objectifiable accounts of the past which will achieve a consensus. This has been accompanied by the erosion of the traditional status of historians, and their role as impartial analysts who possess the necessary skills and knowledge to provide credible histories for the rest of us. Whereas history still has recourse to notions of objectivity in order to define itself, memory is perceived as a more unpredictable affair, coloured by the vagaries of subjective response and amnesia. While the boundary between 'objective' history and 'subjective' memory is no longer clear cut, such distinctions still prevail in critical debates on the topic.

These debates are themselves suffused with nostalgia, which can be defined as a state of longing for something that is known to be irretrievable, but is sought anyway. In so far as it is rooted in disavowal, or suspension of disbelief, nostalgia is generally associated with fantasy and regarded as even more inauthentic than memory. Even though memory is tinged with subjectivity, it can still be regarded as authentic, especially when it comes to eyewitness accounts that provide a record of the impact of momentous events on the lives of individuals - the enormous increase in studies of personal testimony and cultural memory testifies to this. The fact that the eyewitness was actually present at the time invests their recollections with an aura that transcends the knowledge that their experience is reconstructed for the purpose of current agendas, and endows it with authority and emotional power. Once again, the distinction between nostalgia, memory and history has become blurred. The mechanisms of fantasy and suspension of disbelief associated with memory and nostalgia are present in history as well, to a degree. Where traditional approaches prefer to emphasise the differences between them, in order to sanction the legitimacy of history as a means of explaining the world, it is equally possible to see them as a continuum, with history at one end, nostalgia at the other and memory as a bridge or transition between them. The advantage of this formulation is that it avoids the common hierarchy in which nostalgia and some 'inauthentic' forms of memory are relegated and devalued in order to shore up notions of history 'proper'. Instead, it recognises that the three terms are connected: where history suppresses the element of disavowal or fantasy in its re-presentation of the past, nostalgia foregrounds those elements, and in effect lays bare the processes at the heart of remembrance. In that sense, it produces knowledge and insight, even though these may be of a different order from those produced by conventional historical analysis, and may be experienced in different ways.

This gives nostalgia a more interesting and challenging dimension. Rather than being seen as a reactionary, regressive condition imbued with sentimentality, it can be perceived as a way of coming to terms with the past, as enabling it to be exorcised in order that society, and individuals, can move on. In other words, while not necessarily progressive in itself, nostalgia can form part of a transition to progress and modernity. The suspension of disbelief is central to this transition, as nostalgia is predicated on a dialectic between longing for something idealised that has been lost, and an acknowledgement that this idealised something can never be retrieved in actuality, and can only be accessed through images. This process can be seen as an activity of 'let's pretend', or role-play: past events can be recreated so that the audience can experience them in the present, imagine what it was like then, and connect emotionally with representations of the past. Although this is an imaginative, and performative, operation, it also depends on a cognitive response, on the viewers' perception that the representation is not the same as the real thing, and on their critical assessment of the authenticity of the reconstruction. Audiences can consciously enjoy a playful or affecting engagement with history at the same time as exercising their aesthetic judgement. The sense of loss in nostalgic encounters is all the more powerful because it is predicated on the acknowledgement that the past is gone forever. Nostalgia plays on the gap between representations of the past and actual past events, and the desire to overcome that gap and recover what has been lost.

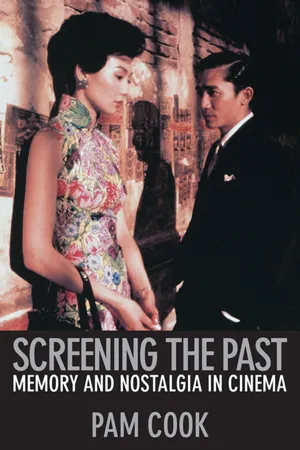

The critiques of memory and nostalgia in film studies are part of a more general engagement in the humanities with issues of history and identity, ranging across disciplines. But they are also partly a response to the emergence of the nostalgic memory film itself, which reconstructs an idealised past as a site of pleasurable contemplation and yearning. This is a very broad category, incorporating heritage cinema, period melodramas and westerns, as well as remakes and pastiches. While there have always been nostalgic memory films, the past 30 years have seen a substantial increase in their production. In the postmodern electronic era, as reality becomes increasingly virtual, the desire to find some form of authenticity has intensified. At the same time, consumer capitalism has taken full advantage of nostalgia to market commodities, including films and television programmes. Nevertheless, modern memory films have not simply exploited nostalgia; in many cases, they have engaged with the process, exploring its limits and questioning traditional notions of history and representation. I have argued that nostalgia cannot be regarded as a simple device for idealising and de-historicising the past, as has frequently been claimed. Similarly, the nostalgic memory film, even in its most apparently innocent manifestations, has the potential to reflect upon its own mechanisms, and to encourage reflection in audiences. The more self-reflexive nostalgic films can employ cinematic strategies to actively comment on issues of memory, history and identity, and it is to such examples that I now turn, I shall explore two recent films that can be regarded as overtly nostalgic, but which also set out to reveal the complexities of the relationship between history and memory. The first is Wong Kar-wai's In the Mood for Love (2000), which has been hailed as a masterpiece of new Asian cinema, but has also been criticised for aestheticising and effacing history. The second is Todd Haynes' acclaimed tribute to Douglas Sirk melodramas of the 1950s, Far From Heaven (2002), which sparked a debate about the value of cinematic pastiche. It is no coincidence that both films foreground costume, performance and masquerade to illuminate issues of authenticity, memory and identity. They take full advantage of the nostalgic gaze at exquisitely designed period clothes and sets characteristic of historical fiction, but they use cinematic strategies of nostalgia in different ways to question the relationship between past and present, then and now. In both cases, costume, set design and performance play a crucial role in the films' investigation of history, memory and time.

In the Mood for Love: a dress tells the time

In the Mood for Love is set in Hong Kong in the 1960s. This was a key period for Wong Kar-wai himself, who moved from Shanghai to Hong Kong in 1963, at the age of five. In interviews he has declared that he wanted to recreate that time and place through his own recollections, and although In the Mood for Love is not strictly autobiographical it is littered with memories of personal significance to the director. Iconographic memorabilia and period styles blend with snatches of music and other cultural references to produce a kind of meditation on the passage of time, viewed as a fusion of past and present encapsulated in a single, apocryphal moment. Wong's trademark stylistic flourishes are evident in the ironic use of clocks to evoke a relentless forward momentum, and the dream-like slow-motion and step-motion effects that imply the reverse, a slowing-down of cinematic time that seems to resist the inevitability of history. The mélange of cultural allusions contributes to this sense of nostalgic reverie: the film reconstructs 1960s Hong Kong through a promiscuous blend of references to popular cultural forms such as songs, films, novels and fashions from the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, spanning traditional and modern manifestations. All this suggests that In the Mood for Love is less concerned with exploring colonial history than in taking a self-indulgent, backward look at an idealised, lost culture and way of life.

Indeed, even those who admire the film find it conservative in some respects. As well as those who criticise it for ignoring the sociopolitical context, others see in its romance of frustrated desire a regressive celebration of traditional Chinese melodramas that seem to endorse self-sacrifice and moral restraint as social imperatives. One of the key reference points for In the Mood for Love has been identified as Fei Mu's celebrated 1948 melodrama Spring in a Small City (recently remade by Zhuangzhuang Tian as Springtime in a Small Town [2002]), in which a married woman forgoes her own desire for a former lover and decides to stay with her ailing husband, whom she no longer loves. There are resonances here with the theme of quaint, old-fashioned morality that prevents Maggie Cheung as Su Li-zhen and Tony Leung as Chow Mo-wan from consummating their adulterous passion in Wong's film. Another reference point, not remarked upon to the same extent, is the similarity between In the Mood for Love and David Lean's 1946 film Brief Encounter, which is discussed in detail later in this volume. While the debt to Chinese melodrama, and to Spring in a Small City in particular, is not in dispute, Wong's film actually corresponds closely to Brief Encounter in its formal structure, themes and visual iconography. Without suggesting an intentional connection or tribute, in the light of the British contribution to Hong Kong's colonial past, it seems relevant to acknowledge those correspondences, while respecting the differences between the two films.

Like In the Mood for Love, Brief Encounter tells the story of an unconsummated romance between two married people, a middle-class housewife and the young doctor with whom she falls in love. It is a memory film, looking back from the perspective of Britain after the Second World War to the 1930s, perceived as a more innocent time. The complex structure, told in flashback through the her...