eBook - ePub

Marketing Apocalypse

Eschatology, Escapology and the Illusion of the End

- 314 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marketing Apocalypse

Eschatology, Escapology and the Illusion of the End

About this book

The present volume of essays examines the extent to which the end of marketing is nigh. The authors explore the present state of marketing scholarship and put forward a variety of visions of marketing in the twenty first century. Ranging from narratology to feminism, these suggestions are always enlightening, often provocative and occasionally outrageous. Maketing Apocalypse is required reading for anyone interested in the future of marketing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marketing Apocalypse by Jim Bell,Stephen Brown,David Carson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

APOCAHOLICS ANONYMOUS

Looking back on the end of marketing

Stephen Brown, Jim Bell and David Carson

APOCALYPSE THEN

It is no exaggeration to state that the end of the world goes back to the beginning of time, or the dawn of civilisation at least. As the copious histories of the End make clear, humankind is, and always has been, addicted to the apocalypse (e.g. Rubinsky and Wiseman 1982; Friedrich 1982; Reiche 1985; Kamper and Wulf 1989; Bull 1995a). Whether it be the second coming of Christ, the ancient Norse myth of Ragnarök, the Hindu doctrine of Kali Yuga, the final blast of Israfil’s trumpet anticipated by Islam, the well-publicised predictions of the Mayan and Aztec calenders (which disconcertingly converge on the year 2012 A.D.), or the multiplicity of secular apocalypses expounded by contemporary Jeremiahs, the idea of impending doom looms large in the human psyche. We are, so it seems, transfixed by terminal visions, mesmerised by the millennium, entranced by eschatological expectations, consumed by chiliastic conjecture and, thanks to the protection afforded by the welllubricated prophylactic of prophesy, ever eager to embrace and fructify the end of time (McGinn 1979; Wagar 1982; Ward 1993; Campion 1994; O’Leary 1994). According to Kermode (1967:12), indeed, the second coming was confidently expected in A.D. 195, 948, 1000, 1033, 1236, 1260, 1367, 1420, 1588 and 1666, to name but a few. The Jehovah’s Witnesses alone have rescheduled the end of the world on nine separate occasions (1874, 1878, 1881, 1910, 1914, 1918, 1925, 1975, 1984). And Mann’s (1992) recent compilation of projected terminations stretch from 1998 to 6300 A.D., though his inventory is by no means exhaustive.

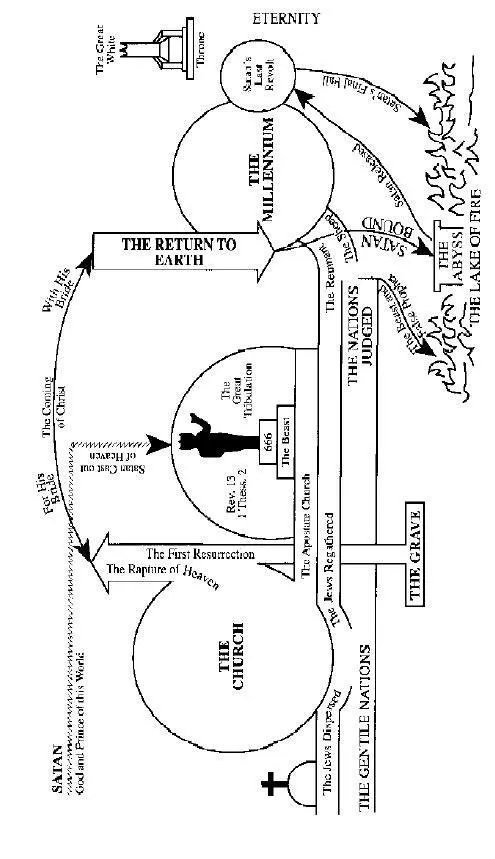

Just as this seemingly insatiable human desire for Dies Irae has made itself felt at many different times, so too it is made manifest in many different forms (Chandler 1993; Wainwright 1993; Skinner 1994; Kumar 1995a). These range from the rivers of molten metal awaited by the followers of Zoroaster, the Stoic prophesy of universal conflagration and the ancient Egyptian god Amun’s determination to return the world to its original watery state (as recorded in the Book of the Dead c. 2000 B.C.), to some Native Americans’ belief in the Great White Beaver of the North, which is slowly gnawing its way through the tree-trunk that supports the Earth precariously above a bottomless pit. A bottomless pit also features in the principal Judeo-Christian version of the End, that recounted in the book of Revelation (Figure 1.1), alongside the appearance of the Antichrist, the Parousia (second coming), the cosmic battle of Armageddon, the one-thousand-year earthly reign of Christ, the loosing of Satan, the Last Judgement, the descent of New Jerusalem and the onset of everlasting life (or, for the contributors to this volume at least, eternal damnation).

Although comparatively few people now consider this Biblical schema to be the literal truth–the growth of Christian fundamentalism notwithstanding (Cotton 1995; Weiss 1995; Economist 1995)–the modern, desacralised world is not exactly short of apocalyptic surrogates. Granted, the prospect of a largescale thermonuclear conflict has receded in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet empire, but a more than adequate substitute for the position of Public Eschatology Number One has been found in the shape of imminent ecological catastrophe–greenhouse effect, global warming, ozone layer depletion, melting ice-caps et alia . There are, moreover, any number of alternative end-times scenarios including overpopulation, resource depletion, famine and pestilence (AIDS in particular), earthquakes, tidal waves, incoming meteorites, alien invasions and, depending upon which scientific theory one subscribes to, the sudden implosion, or gradual running down, of the universe (Frankel 1987; Chandler 1993; Quinby 1994; Lorie 1995).

This multiplicity of imagined endings is paralleled in certain respects by terminological profusion, some would say con fusion. As a glance at almost any work of prophetic literature makes clear, there is a rich and resonant vocabulary associated with the End–Gog, Magog, Armageddon, Abbadon, etc. Although for most people, and the sub-editors of tabloid newspapers, the contents of this apocalexical lucky-bag are ail-but interchangeable, it is necessary to stress that end-times terms are not synonymous. True, the precise definitions of words like eschatology, teleology, chiliasm, millenarianism and apocalypse are mutable, prone to disputation and, in practice, inclined to shade into each other, but they are by no means one and the same. Eschatology, for example, is the study of endings, the end of the world in particular, whereas teleology presumes that history has an ‘end’, in the sense of destination, culmination or purpose. Thus, it is perfectly possible to conceive of an historical destination, such as a communist or Utopian state, which does not necessarily involve the end of the world. Millenarianism and chiliasm, likewise, pertain to the scriptural contention that Christ will rule for a thousand years (the millennium) prior to the final battle with Satan and the commencement of the Kingdom of God. In practice, however, the former term is often used to describe any religious or secular movement that seeks to establish an earthly paradise, or suffers from calendrically induced anxieties, and the latter is usually reserved for believers in Biblical-style millennial milieux (Friedländer 1985; Campion 1994; O’Collins 1994; Bull 1995b).

More importantly perhaps for the purposes of the present discussion, the word ‘apocalypse’ is widely associated with death, destruction, chaos and carnage. It is, in effect, an umbrella or colloquial term for the signs and wonders, the murder

Figure 1.1 Visualising the End

Source: adapted from Boyer (1992)

and mayhem, the weeping, wailing and gnashing of teeth that purportedly presage the end of the world. Strictly speaking, however, apocalypse means ‘revelation’, the unveiling of that which is hidden, albeit in the Judeo-Christian tradition this unveiling involves end-times scenes of total disaster and utter devastation (Boyer 1992; Rowland 1995). More strictly still, the word apocalypse refers to a distinctive literary form which flourished in the period 100 B.C. to 200 A.D. (at least sixteen and possibly as many as seventy Judaic apocalypses have been identified). According to Collins (1984:4), in fact, apocalypse is ‘a genre of revelatory literature with a narrative framework, in which a revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendent reality which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation and spatial, insofar as it envisages another, supernatural world’. As a rule, furthermore, most apocalypses consist of a three-stage plot sequence variously described as ‘crisis, judgement and vindication’ (McGinn 1995), ‘destruction, judgement and regeneration’ (Fortunati 1993), and, ‘decadence, end and renovation’ (Kermode 1995). They also tend to be pseudonymous, in that the works are almost invariably attributed to a revered sage or leader from the past–Ezra, Enoch, Daniel and so on. In a very real sense, then, the apocalyptic author is positioned at a point beyond time and proceeds to look back, so to speak, on the end of the world (Zamora 1989; Noakes 1993; O’Leary 1994; Boyarin 1996).

Although some Biblical scholars have manned the definitional barricades, arguing that ‘apocalypticism in the full sense of the word…existed only for about 200 years, and formed a unique mentality’ (Funkenstein 1985:57), it is generally accepted that several major variants on the eschatological theme can be discerned. Quinby (1994), for example, distinguishes between divine, techno logical and ironic apocalypses; Kermode (1985) identifies what he terms the apocalyptic set, canon and interpretations, and, Bull (1995b) notes sacred and secular strains of apocalypse, though the former is sub-divided into spiritual and histor ical varieties. Such schemata tend to differ in their taxonomic detail, but they do suggest three main types of apocalypse, the first of which is the traditional scriptural model espoused by religious fundamentalists, who anticipate the End in accordance with God’s plan and foresee a heavenly home for the chosen few. The second is a desacralised version of the same, in that it expects earthly destruction by the hand of humankind itself, whether it be thermo-nuclearinduced immolation, environmental catastrophe, contagious illness or whatever. The third category, by contrast, comprises an anti-nomian, rebellious, nihilistic, essentially apocalyptic worldview that is apparent in many strands of latetwentieth-century popular culture. Described in lurid, often grotesque, detail in Parfrey’s (1990) notorious compendium, Apocalypse Culture, this contemporary mindset is made manifest in films (The Rapture, Terminator 2: Judgement Day), books (Stephen King’s The Stand, J.G.Ballard’s Billennium ), rock music (van Halen’s The Seventh Seal, Def Leppard’s Armageddon It ), and, not least, the dyspeptic ruminations of the postmodern intelligentsia (see Greisman 1974; Wagar 1982; Friedländer 1985; Boyer 1992; Dellamora 1996a; Pask 1996).

APOCALYPSE WHY

If, for want of a better word, we are apocaholics, it seems reasonable to inquire into the causes of our addiction to the End. According to the celebrated literary critic, Frank Kermode (1967, 1985, 1995), it is nothing less than a fundamental correlate of the human condition. Human beings require consonance, they need things to make sense and are predisposed to impose structure on the existential flux, chaos and fragmentation of our daily lives. The idea that we live within a sequence of events between which there is no relation, pattern or progression is simply unthinkable. Hence, he argues, humankind is inclined to foist a beginning, middle and end upon time, whether it be the changing of the seasons, the mundane ticking of a clock (tick-tock being a complete narrative, as opposed to the unending succession that is tick-tick-tick), or, indeed, the entire western literary canon with its predilection for once-upon-a-times and happily-ever-afters (Abrams 1971; White 1980; Zamora 1989). Just as our individual lives have a clearly discernible plot structure, so too we ‘project our existential anxieties on to history’ (Campion 1994:346), ‘we hunger for ends and for crises’ (Kermode 1967:55), we can’t avoid ‘a certain metaphysical valorisation of human existence’ (Eliade 1989: vii).

Another, closely related, interpretation of apocalypse is that it is primarily a form of escape . For Eliade (1989), humanity’s seemingly insatiable desire for endings is actually an indication of optimism and hope, in so far as the prospect of redemption and renewal enables people to cope with the trials, tribulations and torments of their quotidian existence (see also Cohen and Taylor 1992; Rojek 1993). The fact that things seem to be getting worse provides a curious form of comfort, since it indicates that the end is at hand, that justice will be done. The hour, after all, is reputed to be darkest just before dawn (Reiche 1985; McGinn 1995). It is surely no accident, moreover, that the proponents of apocalypse invariably assume that they will be among the survivors, that they comprise the elect, that, despite the dreadful, short-term sufferings soon to be endured, rewards await them in the world to come (Rowland 1995; Shaffer 1995). In this respect, it is noteworthy that very few religious eschatologies assume that the end of the world is total, final or absolute (Eliade 1991). On the contrary, there is always something after the end, usually a qualitatively different–eternal, perfect, immeasurably superior–environment where, as one of the most lyrical and moving passages in the Bible makes abundantly clear, ‘God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away’ (Revelation 21:4).

While many may accept McGinn’s (1995:76) declaration that declarations of the end are, in the end, expressions of ‘hope for a better time to come’, or appreciate Kumar’s (1995a:202) assertion that, ‘the apocalyptic myth holds in an uneasy but dynamic tension the elements of both terror and hope’, the very idea of wishing for the end is undeniably difficult to comprehend. Indeed, as the recent case of the Solar Temple cult amply illustrates, the active pursuit of Doomsday– the desire, as it were, to accelerate Armageddon–strikes most non-initiates as completely wrongheaded, utterly bizarre and, if events involving the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas, are at all representative, nothing less than sheer lunacy. 1 Lifton (1985), however, maintains that these ostensibly eccentric behaviours are actually a manifestation of a primordial thanatic impulse, a universal urge towards the void. Certainly, there is no denying the orgiastic excitement associated with the unleashing...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- The Shallow Men

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- List of contributors

- Preface

- 1 Apocaholics Anonymous Looking back on the end of marketing

- Part I Crisis

- Part II Judgement

- Part III Renovation

- Name Index

- Subject Index